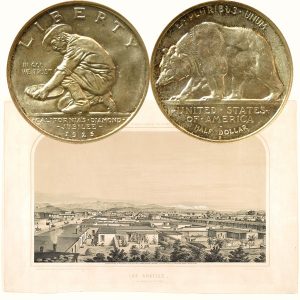

Today, the California Diamond Jubilee Commemorative Silver Half Dollar Coin remembers when the American flag first waved over Los Angeles on August 13, 1846.

From the Santa Fe Employes’ Magazine of December 1910:

=====

On the day of Sloat’s departure Stockton issued a proclamation to the people of California, in which address, among other things, he declared that the Mexican government and its military leaders had without cause for a year been threatening the United States with hostilities; that, in pursuance of these threats, they had, with seven thousand men, attacked a detachment of two thousand United States troops, by whom they were routed.

General Castro, the Mexican commander-in-chief of the military forces in California, had “shamefully violated international law and national hospitality by hunting and following, with wicked intent, Captain Fremont of the United States army and his band of forty men, who had entered California for rest and refreshment after a dangerous scientific expedition over the mountains.

Stockton asserted further that, until redress could be gained from Mexico, military occupation of Santa Fe and Monterey had been determined upon.

Yet the native officials, instead of remaining under American protection to perform their duties, had fled, leaving the people in a state of anarchy and confusion.

Since the local officials had left Stockton felt it his duty to all concerned, and California in particular, to end the lawless depredations of Castro’s men against peaceful inhabitants.

As he could not accomplish this mission by remaining in any of the seaports, he would immediately march against “these boasting and abusive chiefs, who, unless driven out, will, with the aid of hostile Indians, keep this beautiful country in a constant state of revolution and blood.”

He declared further that the general of the California forces was a “usurper, who had been guilty of great offenses, who had impoverished the country, who had deserted his post when worst needed, who had come into power by force and who must be expelled by force;” in fact, Mexico seemed compelled from time to time to abandon California to “the mercies of any wicked man who could muster one hundred men in arms.”

In fairness to truth, however, it must be said that this proclamation was badly overdrawn, inaccurate in its presentation of Castro’s attitude toward Fremont, and decidedly vague as to the real meaning it conveyed, which was simply a determination to occupy and hold California.

Although bombastic, the document was fully in accord with the Mexican way of doing things, yet, as further events proved, Stockton’s methods of warfare were not those of Mexico.

In this official act Stockton may have been influenced by Fremont.

Both of these men were ambitious, and, as they were acting at a long distance from home, with all honor for what they did, perhaps it was natural for them to picture their opposition as great as possible — to do a little “grandstand” work — in order to win a full measure of success when success was achieved.

Now to trace briefly the fortunes of the California Mexicans after the American invasion.

Immediately after Sloat’s arrival General Castro had fled southward from Santa Clara with about two hundred men, accompanied by Juan B. Alvarado, a distinguished citizen but who held no military command.

Halting at Los Ojitos Castro sent word to General Pico at San Luis Obispo informing the latter of Sloat’s invasion.

For a time these quarreling leaders seem to have laid aside their differences and to have decided to defend Los Angeles, the capital, against the Americans.

On July 24, having assembled his legislators at Los Angeles, Pico aroused considerable patriotism by his oratory, as well as by the speeches of certain other speakers whom he had chosen for the occasion.

Castro and his small army soon arrived, and measures for resistance were at once taken. Yet all plans of defense were entered upon in a decidedly listless manner, and cooperation, if any, on the part of subordinate officials, was lukewarm.

Many people were in unquestioned sympathy with the invaders, while others held aloof from what seemed to be a useless struggle. Many had no faith in their leaders.

While Pico and Castro made a show of friendship, their subordinates were in a continual quarrel.

Indeed, while Pico was away the people of Los Angeles had organized to fight Castro. Hence the men of southern California were slow to join the “regular” army.

Appeals to citizens in the outlying districts for military duty were generally met by great “feelings” of patriotism — accompanied by regrets that the Indians were dangerous and thus it was unsafe to leave home.

The California government had lost both credit and reputation. The ranch owners even hesitated to give fire arms and horses for their country’s cause.

In the meantime Fremont had landed at San Diego, while Stockton, with three hundred and sixty marines, had disembarked at San Pedro.

Sailing out of Monterey on August 1 the latter had stopped en route at Santa Barbara, raised the American flag and left a small garrison, arriving at San Pedro on the sixth.

On August 7 two Mexican envoys from Los Angeles visited Stockton, bearing a note from Castro, in which the latter asked an explanation for the Americans’ presence and at the same time sought to negotiate. To this Stockton would not assent.

Finding there was no chance to negotiate, Castro and his officers held a council of war at the mesa on August 9. Here he decided that he had done all in his power to oppose the Americans, and he regretfully admitted that he could not succeed in his purpose.

He thought it best for him to leave the country at once to report the California situation to his supreme government.

Furthermore, he respectfully invited Governor Pico to accompany him as a traveling companion as far as Sonora.

Both leaders wrote affecting farewells to their people, extracts from both of which are here with presented.

On August 9 Castro delivered the following: With my heart full of the most cruel grief. I take leave of you. I leave the country of my birth, but with the hope of returning to destroy the slavery in which I leave you. For the day will come when our unfortunate fatherland can punish this usurpation, as rapacious as unjust, and in the face of the world exact satisfaction for its grievances.

On the following day Pico wrote this address: My friends, farewell! I take leave of you. I abandon the country of my birth, my family, my property, and whatever else is most grateful to man, all to save honor. But I go with the sweet satisfaction that you will not second the deceitful views of the astute enemy; that your loyalty and firmness will prove an inexpugnable barrier to the machinations of the invader. In any event, guard your honor and observe that the eyes of the entire universe are upon you.

On the night of August 10 Pico and Castro abandoned their country to its fate and left Los Angeles for Mexico.

Having addressed their farewells, flight seemed their best means of safety.

In spite of their loud expressions of grief and regret, it was their own misconduct and avarice which had destroyed confidence in themselves and made the occupation of California by a small American force easily possible.

In the meantime Stockton had been drilling his three hundred and sixty marines, and on August 11 he started for Los Angeles.

On the afternoon of that day he learned of Castro and Pico’s retreat, whereupon he sent one hundred and fifty of his men back to San Pedro.

His progress was slow, as he had only oxen or the men themselves to draw the artillery.

Reaching Castro’s camp he found ten abandoned cannon, four of which had been spiked.

After a march of two days Stockton’s men drew near the city, where they were joined by Fremont and his party, who had come up from San Diego.

The combined forces then entered Los Angeles without opposition on August 13, 1846, and the American flag for the first time waved over the capital of California.

=====

The California Diamond Jubilee Commemorative Silver Half Dollar Coin shows with an image of Los Angeles, circa 1857.