Today, the Louisiana State Quarter Coin remembers when General Jackson arrived at New Orleans on December 2, 1814.

He arrived not only to defend New Orleans but also to defend the fledgling country from a British conquest.

From the Chalmette National Historical Park Louisiana by J. Fred Roush, published in 1958:

=====

Louisiana in 1814

Louisiana was founded by the French, and its early growth was under their rule. Then followed a period of Spanish domination. In 1803, it was French again briefly before becoming American as part of the Louisiana Purchase.

Even under American rule, many French refugees from the wars in the West Indies and Europe kept New Orleans, Louisiana’s chief city, predominately Latin. Also, the city had all the elements of a cosmopolitan seaport.

Although Louisiana was admitted as a state in 1812, it still seemed like a foreign country to people from Kentucky or Tennessee.

W. C. C. Claiborne, a Virginian by birth, was Governor of Louisiana in 1814.

As head of the militia, he could not find enough reliable troops to defend the state. Only a few regulars were stationed at New Orleans.

Many planters, remembering the slave uprising of 1811, did not want to leave to defend the frontiers. In spite of all this, the spirit of the militia strengthened as the danger of British invasion came closer.

In the early years of “American domination” there was enmity between Americans and Creoles (white Louisianans of French or Spanish descent); however, Claiborne wrote Jackson that the majority of Creoles and Europeans in New Orleans were loyal, but that many favored Spain or England.

In this connection, the British believed that the inhabitants of Barataria, who lived on the Louisiana coast about 50 miles south of New Orleans, would aid them in their conquest of Louisiana.

The Baratarians admitted smuggling and privateering, and were accused of piracy. They were led by the mysterious Lafitte brothers, Jean and Pierre, but Barataria existed before their arrival about 1810.

After 1804, when the importation of slaves became illegal in Orleans territory, smuggling them in was another line of “business” for these privateers.

In the year before the British invasion, the Baratarians were having more trouble than formerly with both State and Federal authorities.

On September 3, 1814, British officers appeared at Barataria and offered Jean Lafitte land in British North America, protection of his property and person, $30,000 in cash, and the rank of captain in their navy, if he would join them.

Lafitte asked for time to consider their offer, and promptly wrote to the Governor and to a member of the legislature. He told them of the British offer, enclosed documents to prove his story, and offered to help the Americans in return for a pardon for himself and his men.

These letters were received in New Orleans on September 5. On advice from his military committee, Governor Claiborne declined Lafitte’s offer, but he wrote soon after that the privateers might become useful to the United States.

Pierre Lafitte, who had been arrested and jailed in New Orleans, escaped about this time, possibly with help from those in high places. Barataria was destroyed by United States forces under Col. G. T. Ross and Commodore D. T. Patterson, between September 16 and 19.

The Baratarians fled to the swamps rather than resist. Their avoidance of conflict, following Jean Lafitte’s offer of help, was making some impression on the American authorities.

On October 30, Claiborne wrote to the United States Attorney General, recommending clemency for the smugglers. The Americans and Baratarians were gradually coming together as the British prepared their grand assault.

Preparing to Defend New Orleans

Andrew Jackson arrived in New Orleans for the first time on December 2, 1814.

In his history of the campaign, Maj. A. Lacarriere Latour, Jackson’s military engineer, said: “It is scarcely possible to form an idea of the change which his arrival produced on the minds of the people.”

That such a man was needed is shown by these words of Charles E. A. Gayarre, the distinguished Creole historian of Louisiana:

Where (Jackson) was as chief, there could be . . . but one controlling and directing power. All responsibility would be unhesitatingly assumed and made to rest entirely on that unity of volition which he represented. Such qualifications were eminently needed for the protection of a city containing a motley population, which was without any natural elements of cohesion, and in which abounded distraction of counsel, conflicting opinions, wishes and feelings, and much diffidence as to the possibility of warding off an attack.

Jackson commenced work with a minimum of formalities. He immediately reviewed the Battalion of Uniform Companies of the Orleans Militia.

He then chose aides from among the prominent local citizens, and established headquarters at 106 Royal Street. From there he issued orders for the disposition of troops for the defense of New Orleans.

In 1814, the city, about 105 miles from the mouths of the Mississippi, was almost an island surrounded by swamps and marshes, lakes, and the river.

Most of the firm ground was along the banks of the Mississippi. A mile or so from the river, the almost impenetrable cypress swamps began. These gradually gave way to marshes that were filled with tall, razor-edged reeds.

The marshes became more watery as the shores of shallow lakes were reached: Maurepas, Pontchartrain, Borgne, and many smaller ones. Lake Borgne, was an arm of the Gulf of Mexico.

The only practicable ways from the lakes to the river were along the bayous. The marshes and swamps were criss-crossed by many of these sluggish streams, some navigable by small boats.

The banks of the bayous were the only partly firm ground in the extensive morass. It seemed likely that the British would come by way of Lakes Borgne and Pontchartrain, and Bayou St. John, or up the Mississippi itself.

Jackson kept some troops on the alert in New Orleans, and sent others to guard the water approaches. A fleet of gunboats watched the entrance to the lakes.

Some of the bayous were blocked with logs and earth. These arrangements having been completed within 48 hours of his arrival, Jackson inspected the defenses down the Mississippi, where he ordered the strengthening of Fort St. Philip.

On his return, he inspected the defenses of the lakes, Chef Menteur, and the Plain of Gentilly, these being north and east of the city.

With his defenses in order, Jackson awaited the next move by the British.

=====

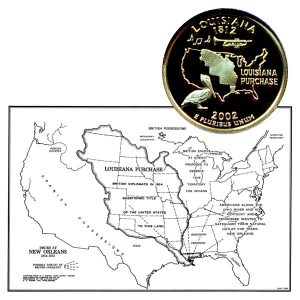

The Louisiana State Quarter Coin shows with a map listing the issues at New Orleans in 1814-15 and the importance of the area to the British.