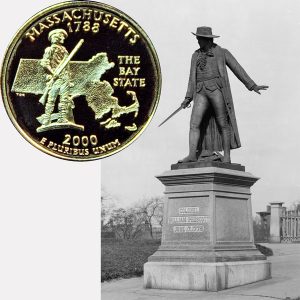

Today, the Massachusetts State Quarter Coin remembers Colonel Prescott and his hastily gathered group of me who rapidly built a defensive redoubt on June 16, 1775 in preparation for the Battle of Bunker Hill.

From the History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent by George Bancroft, published in 1867:

=====

The British forces gave signs of shame at their confinement and inactivity. “Bloody work” was expected, and it was rumored that they were determined, as far as they could, to lay the country waste with fire and sword.

The secretary of state frequently assured the French minister at London, that they would now take the field, and that the Americans would soon tire of the strife. The king of England, who had counted the days necessary for the voyage of the transports, was “trusting soon to hear that Gage had dispersed the rebels, destroyed their works, opened a communication with the country,” and imprisoned the leading patriots of the colony.

The peninsula of Boston, at that time connected with the mainland by a very low and narrow isthmus, had at its south a promontory then known as Dorchester Neck, with three hills, commanding the town.

At the north lay the peninsula of Charlestown, in length not much exceeding a mile; in width, a little more than a half mile, but gradually diminishing towards the causeway, which kept asunder the Mystic and the Charles, where each of those rivers meets an arms of the sea.

Near its northeastern termination rose the round smooth acclivity of Bunker Hill, one hundred and ten feet high, commanding both peninsulas.

The high land then fell away by a gradual slope for about seven hundred yards, and just north by east of the town of Charlestown, it reappeared with an elevation of about seventy-five feet, which bore the name of Breed’s Hill.

Whoever should hold the heights of Dorchester and Charlestown, would be masters of Boston.

About the middle of May, a joint committee from that of safety and the council of war, after a careful examination, recommended that several eminences within the limits of the town of Charlestown should be occupied, and that a strong redoubt should be raised on Bunker Hill.

A breastwork was thrown up across the road near Prospect Hill; and Bunker Hill was to have been fortified as soon as adequate supplies of artillery and powder should be obtained; but delay would have rendered even the attempt impossible.

Gage, with the three major-generals, was determined to extend his lines north and south, over Dorchester and Charlestown; and as he proposed to begin with Dorchester, Howe was to land troops on the point; Clinton in the centre; while Burgoyne was to cannonade from Boston Neck.

The operations, it was believed, would be very easy; and their execution was fixed for the eighteenth of June.

This design became known in the American camp, and such was the restless courage of the better part of the officers, such the confidence of the soldiers, that it seemed to justify a desire to anticipate the movement.

Accordingly, on the fifteenth of June, the Massachusetts committee of safety informed the council of war that in their opinion, Dorchester heights should be fortified; and they recommended unanimously to establish a post on Bunker Hill.

Ward, who was bound to comply with the instructions of his superiors, proceeded to execute the advice.

The decision was so sudden, that no fit preparation could be made.

The nearly total want of ammunition rendered the service desperately daring; in searching for an officer suited to such an enterprise, the choice fell on William Prescott, of Pepperell, colonel of a regiment from the northwest of Middlesex, who himself was solicitous to assume the perilous duty; and on the very next evening after the vote of the committee of safety, a night and day only in advance of the purpose of Gage, a brigade of one thousand men was placed under his command.

Soon after sunset, the party composed of three hundred of his own regiment, detachments from those of Frye and of Bridge, and two hundred men of Connecticut, under the gallant Thomas Knowlton, of Ashford, were ordered to parade on Cambridge common.

They were a body of husbandmen, not in uniform, bearing for the most part no other arms than fowling pieces which had no bayonets, and carrying in horns and pouches their stinted supply of powder and bullets.

Langdon, the president of Harvard college, who was one of the chaplains to the army, prayed with them fervently; then, as the late darkness of the midsummer evening closed in, they marched for Charlestown in the face of the proclamation, issued only four days before, by which all persons taken in arms against their sovereign, were threatened under martial law with death by the cord as rebels and traitors.

Prescott and his party were the first to give the menace a defiance. For himself, he was resolved “never to be taken alive.”

When with hushed voices and silent tread, they and the wagons laden with entrenching tools had passed the narrow isthmus, Prescott called around him Richard Gridley, an experienced engineer, and the field officers, to select the exact spot for their earth works.

The committee of safety had proposed Bunker Hill; but Prescott had “received orders to march to Breed’s Hill.”

Heedless of personal danger, he obeyed the orders as he understood them; and with the ready assent of his self-devoted companions, who were bent on straitening the English to the utmost, it was upon the eminence nearest Boston, and best suited to annoy the town and the shipping in the harbor, that under the light of the stars the engineer drew the lines of a redoubt of nearly eight rods square.

The bells of Boston had struck twelve before the first sod was thrown up.

Then every man of the thousand seized in his turn the pickaxe and spade, and they plied their tools with such expedition, that the parapet soon assumed form, and height, and capacity for defense.

“We shall keep our ground,” thus Prescott related that he silently revolved his position, “if some screen, however slight, can be completed before discovery.”

The Lively lay in the ferry, between Boston and Charlestown, and a little to the eastward were moored the Falcon, and the Somerset, a ship of the line; the veteran not only set a watch to patrol the shore, but bending his ear to catch every sound, twice repaired to the margin of the water, where he heard the drowsy sentinels from the decks of the men of war still cry: “All is well.”

Putnam also during the night came among the men of Connecticut on the hill; but he assumed no command over the detachment.

The few hours that remained of darkness hurried away, but not till the line of circumvallation was already closed.

As day dawned, the seamen were roused to action, and every one in Boston was startled from slumber by the cannon of the Lively playing upon the redoubt.

Citizens of the town, and British officers, and Tory refugees, the kindred of the insurgents, crowded to gaze with wonder and surprise at the small fortress of earth freshly thrown up, and “the rebels,” who were still plainly seen at their toil.

A battery of heavy guns was forthwith mounted on Copp’s Hill, which was directly opposite, at a distance of but twelve hundred yards, and an incessant shower of shot and bombs was rained upon the works; but Prescott, whom Gridley had forsaken, calmly considered how he could best continue his line of defense.

At the foot of the hill on the north was a slough, beyond which an elevated tongue of land, having few trees, covered chiefly with grass, and intersected by fences, stretched away to the Mystic.

Without the aid of an engineer, Prescott himself extended his line from the east side of the redoubt northerly for about twenty rods towards the bottom of the hill; but the men were prevented from completing it “by the in tolerable fire of the enemy.”

Still the cannonade from the battery and shipping could not dislodge them, though it was a severe trial to raw soldiers, unaccustomed to the noise of artillery.

Early in the day, a private was killed and buried. To inspire confidence, Prescott mounted the parapet and walked — leisurely backwards and forwards, examining the works and giving directions to the officers.

One of his captains, perceiving his motive, imitated his example.

From Boston, Gage with his telescope descried the commander of the party. “Will he fight?” asked the general of Willard, Prescott’s brother-in- law, late a mandamus councilor, who was at his side.

“To the last drop of his blood,” answered Willard. As the British generals saw that every hour gave fresh strength to the entrenchments of the Americans, by nine o’clock they deemed it necessary to alter the plan previously agreed upon, and to make the attack immediately on the side that could be soonest reached.

Had they landed troops at the isthmus as they might have done, the detachment on Breed’s Hill would have had no chances of escape or relief.

The day was exceedingly hot, one of the hottest of the season.

After their fatigues through the night, the American partisans might all have pleaded their unfitness for action; some left the post, and the field officers, Bridge and Brickett, being indisposed, could render their commander but little service.

Yet Prescott was dismayed neither by fatigue, nor desertion. “Let us never consent to being relieved,” said he to his own regiment, and to all who remained; “these are the works of our hands, to us be the honor of defending them.”

=====

The Massachusetts State Quarter Coin shows with an image of a statue of Colonel William Prescott located in Charlestown.