Today, the Half Cent Coin remembers when the first steamship from Europe arrived at the Boston harbor on June 2, 1840.

In A Chronological History of the Origin and Development of Steam Navigation, published in 1895, George Henry Preble included the history behind the Cunard Line and the arrival of the steamship “Unicorn.”

=====

1840 — The Cunard Line —

Mr. Samuel Cunard was one of the first to foresee the great results that might be achieved by the establishment of steamer communication between the United States and England, and as far back as the year 1830, in his quiet home in Nova Scotia, was thinking over the best means of carrying out this project.

In 1838, Mr. Cunard went to England, bent upon putting his idea into operation, and, introduced by Sir James Melville, of the India House, he presented himself to Robert Napier, the eminent marine engineer, and the result of their deliberations was that Mr. Cunard gave Mr. Napier an order to build four steamships for the Atlantic service.

The four vessels were to be of 900 tons each, and 300 horse-power. Mr. Napier advised the building of larger vessels, and ultimately it was arranged that the four vessels should each be of 1200 tons burden and 440 horse-power.

The project now assumed a proportion beyond the resources of a private individual, and Messrs. Cunard and Napier, taking counsel together, hit upon the idea of forming a company.

Messrs. Burns, of Glasgow, and Messrs. MacIver, of Liverpool, after having run coasting steamers in keen rivalry for several years, in 1830 amalgamated their undertakings, and this firm of Burns & MacIver was at the time that Mr. Cunard came to England one of the most prosperous shipping companies in Great Britain.

The proposal to form an Atlantic steamship company was mooted to Messrs. Burns & MacIver by Mr. Napier, and the outcome was the establishment, in 1839, of the “British and North American Royal Mail Steam-Packet Company.”

This official title being rather lengthy for hurried utterance, a convenient substitute was found in the simple phrase, “Cunard Line.”

This phrase has now become familiar as a nautical term from Sandy Hook to the Suez Canal, and from Scotland to the West Indies.

Samuel Cunard may be justly regarded as the father of the line, and his enterprising partners, the MacIvers and Burnses, have shown themselves to be quite adequate to the grave responsibilities which they then assumed.

About this time the government decided, on grounds of public convenience, as well as with the view of promoting the extension of steam navigation, to abandon the curious old brigs which had been used for so many years for the conveyance of the mails across the Atlantic and to substitute steam mail-boats.

The Admiralty accordingly advertised for tenders for this service, and the Great Western Steam Shipping Company and the newly-formed company of Messrs. Cunard, Burns & MacIver were the only competitors.

The tender of the latter firm was accepted, and a seven years’ contract was entered into between the Lords of the Admiralty on the one part, and Samuel Cunard, George Burns, and David MacIver on the other part, for the conveyance of mails fortnightly between Liverpool and Halifax, Boston, and Quebec, in consideration of the annual sum of £60,000.

One of the conditions of the bargain was that the ships engaged in this service should be of sufficient strength and capacity to be used as troop-ships in case of necessity.

The first four ships built under Mr. Napier’s direction for the Cunard Company were the “Britannia,” the “Acadia,” the “Caledonia,” and the “Columbia.”

The “Unicorn” was dispatched from Liverpool on the 16th of May, 1840, to be placed on the branch route to Newfoundland, and made the passage to Boston in nineteen days.

There was considerable excitement in Boston on the afternoon of Tuesday, June 2, 1840, when it was announced that Mr. Cunard’s steamship “Unicorn,” Captain Douglas, was entering the harbor.

The arrival of the first regular steam-packet from Europe had been looked forward to with interest, as marking a most important epoch in the commercial relations of the New World and the Old.

The people, young and old, men, women, and children, assembled as the “Unicorn” approached Long Wharf, and the scene on water and land was inspiring and enthusiastic. Cheers rent the air, handkerchiefs and hats were waved, as the “Unicorn” approached.

The United States ship- of-the-line “Columbus,” moored in the channel, hoisted the English ensign at the fore, and her band played the national tunes of England and the United States, and the revenue cutter “Hamilton,” which made a gallant appearance dressed in flags and bunting, fired a salute.

For a short time the “Unicorn” “lay to” off the wharf, and as Captain Sturgis, commanding the “Hamilton,” stepped on board and tendered a welcome to Captain Douglas, a round of cheers went up from the crowd.

Then the “Unicorn” steamed along the water-front and wharves to the vicinity of the navy-yard, and proceeded to the Cunard wharf at East Boston, which had been recently built, and at that time was considered elegant and spacious in every respect.

As she passed the revenue cutter she was again saluted, and returned the salute.

Salutes were also fired from the wharf.

On two lofty flag-staffs erected on the extremity of the wharf British and American ensigns were hoisted.

When moored at the wharf many people hastened on board to exchange congratulations with the captain, officers, and passengers.

The “Unicorn” encountered a good deal of rough weather on her voyage, but proved a good and stanch boat.

Her machinery worked well, and the passengers were well pleased with their accommodations.

She brought out twenty-seven cabin passengers to Halifax, and twenty- four to Boston, and files of London papers to the 15th of May, of Liverpool papers to the 16th, and of Paris papers to the 13th.

The day following her arrival the Boston newspapers were full of copious extracts from the foreign papers which the “Unicorn” brought, and which were appended to the short notice of the important event.

Regret was expressed that the political and commercial intelligence by the arrival was not more important, but the heading, “Sixteen Days Later from Europe!” clearly indicated that one of the most important advantages that was anticipated by the opening of steamship communication between Boston and Liverpool was the quicker exchange of news with the Old World.

The arrival of the “Unicorn” was the talk of the city, and the city felt called upon to take proper recognition of so significant an occurrence, and three days later, on Friday, June 5, the city authorities extended a welcome to Samuel Cunard, Jr., a son of Samuel Cunard, and Captain Douglas, commander of the “Unicorn,” at Faneuil Hall.

The cradle of liberty was beautifully festooned with the flags of the United States and Great Britain, and was otherwise decorated in a very tasteful manner.

The city officials and invited guests marched in procession to the hall from the old City Hall, where a banquet had been prepared for about four hundred and fifty persons.

Hon. Jonathan Chapman, the Mayor of Boston, acted as the presiding officer and master of ceremonies.

In his address of welcome he enlarged upon the vast importance to Boston of steam navigation with Europe in connection with the western railroad.

The sentiment which he offered in conclusion was: “Commercial enterprise — it waked up the dark ages; it launched mankind upon the sea of improvement; it guided the bark and spread the sail until a sail is no longer needed to join the two continents together.”

Mr. Cunard, Jr., was then called up, and made a pleasant response, and the band played “God Save the Queen.”

Commander Douglas gave a brief account of the voyage, and said the steamers that were being built for the line were to be much larger, and he had reason to believe that the passage would be made in fifteen days.

To a toast in honor of England and America, Hon. Mr. Grattan, her Britannic Majesty’s consul, responded, and then, the Mayor calling for volunteer toasts, there followed the most sparkling wit and sentiment.

Hon. Robert C. Winthrop, then Speaker of the House, made an eloquent speech, and, referring to the dictum of Dr. Dionysius Lardner, that steam navigation across the ocean was physically impossible, said that, to all appearances, it was quite as improbable as the scientific doctor’s late elopement to France with Mrs. Heaviside.

The poet Longfellow offered this beautiful sentiment: “Steamships, — the pillar of fire by night and the cloud by day, which guide the wanderer over the sea.”

The Chevalier de Friederichsthal, attached to the Austrian embassy at Washington, M. Gourand, from Paris, and other distinguished foreigners, John P. Bigelow, John C. Park, Hon. George S. Hillard, Nathaniel Greene, then postmaster of Boston, and others, offered appropriate sentiments, and Governor Everett, who was not present, sent a letter.

The celebration was creditable to the city and the event it commemorated, but nevertheless evoked the criticism of censorious individuals, who evidently did not understand or agree with the old proverb, that the way to a people’s heart is through their stomach.

In comparison with steamships which now enter Boston and New York, the “Unicorn” was small and insignificant, and yet the arrival of no craft was ever looked forward to with greater anticipation or more genuine pleasure.

With the arrival of the “Unicorn” began the steam traffic between Boston and London and Liverpool, which has since assumed such large proportions.

Its coming marked a new era in civilization, and was the harbinger of an immense commercial traffic, and a wonderful rapidity of communication between the New World and the Old.

Over forty years have elapsed, and ocean steamers daily arrive, but they excite little interest now.

=====

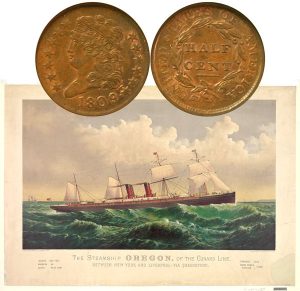

The Half Cent Coin shows with an image of one of the Cunard Line’s steamships, the Oregon, circa 1844.