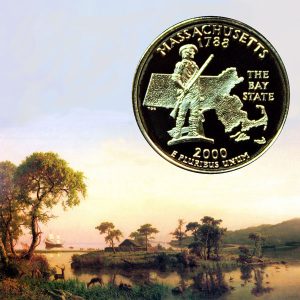

Today, the Massachusetts State Quarter Coin remembers the voyage of Bartholomew Gosnald and his naming of Cape Cod 415 years ago.

From the History of Cape Cod, Annals of Barnstable County by Frederick Freeman, published in 1860:

=====

The first discovery of Cape Cod by a European is generally conceded to Bartholomew Gosnold, the intrepid mariner of the west of England, who, on the 26th of March, 1602, sailed from Falmouth, in Cornwall, in a small bark, with thirty-two men, for the coast known at that time as North Virginia.

Instead of proceeding, as was usual, by the way of the Canaries and West Indies, he kept as far north as the winds would permit, and was, for aught that appears to the contrary, the first Englishman who came in a direct course to this part of the American continent. In fact, it is not certain that any European had ever been here before.

Hakluyt, indeed, mentions the landing of some of Sir Humphrey Gilbert’s men upon some part of the coast, in 1583; but it was evidently farther eastward, upon what was afterwards known as Nova Scotia.

On the 14th of May, 1602, Gosnold made land; and, standing to the south, the next day, May 15, soon found himself “embayed with a mighty headland,” which at first appeared “like an island, by reason of the large sound that lay between it and the main.” This sound he called Shoal Hope.

Near this cape, “within a league of the land, he came to anchor, in fifteen fathoms,” and his crew took a great quantity of cod-fish, from which circumstance he named the land Cape Cod.

It was described by him as “a low, sandy shore, but without dangers, in the latitude of 42°.”

The captain, with Mr. Brierton and three men, ” went to land, and found the shore bold and the sand very deep.”

A young Indian, with plates of copper hanging to his ears, and with a bow and arrow in his hand, came to him, and, in a friendly manner, offered his services. Bancroft confidently asserts that Cape Cod was the “first spot in New England ever trod by Englishmen;” and the eminent historian is, for aught that appears to the contrary, correct in this position.

On the 16th, Gosnold coasted southerly, and, at the end of twelve leagues, discovered a point with breakers at a distance; attempting to double which, he came suddenly into shoal water.

To this point of land he gave the name of Point Care: it is the same now called Sandy Point, and forms the southeastern extremity of the county.

Finding himself surrounded by shoals and breakers, the vessel was brought to anchor until the coast and soundings could be examined by an exploration in the boat.

During this time, some of the natives made him a visit. One of these Indians had a plate of copper upon his breast, twelve inches by six; others had pendants of the same metal suspended from their ears. They all “had pipes and tobacco, of which they were very fond.”

In surveying the coast, breakers were seen off a point of land which he called Gilbert’s Point: it is now called Point Gammon, and forms the eastern side of the harbor of Hyannis.

On the 19th, passing the breach of Gilbert’s Point in four or five fathoms of water, he anchored a league or more to the westward of it.

Several hummocks and hills appeared, which at first were taken to be islands; these were the high lands of Barnstable and Yarmouth.

To the westward of Gilbert’s Point appeared an opening, which Gosnold imagined to have a communication with the supposed sound that he had seen westward of Cape Cod; he therefore gave it the same name, Shoal Hope; but finding the water to be no more than three fathoms deep at a distance of a league, he did not attempt to enter it.

From this opening the land tended to the southwest; and in coasting it he came to an island to which he gave the name of Martha’s Vineyard.

The island he described as distant eight leagues from Shoal Hope, five miles in circuit, and uninhabited; full of wood, vines, and berries.

On it were seen abundance of deer, and around it were taken abundance of cod.

From his station off this island, where the bark rode in eight fathoms of water, he sailed on the 24th, and doubled the cape of another island next to it, which he called Dover Cliff; and this course brought him into a sound, where he anchored for the night, and the next morning sent his boat to examine another cape that lay betwixt him and the main, from which projected a ledge of rocks a mile into the sea, but all above water, and not dangerous.

Having passed around these rocks, the vessel came to anchor again, in one of the finest sounds which he had ever seen.

To this he gave the name of Gosnold’s Hope. On the northern side of it was the main; and on the southern, parallel to it, at a distance of four leagues, was a large island, which he called, in honor of his Queen, Elizabeth.

On this island he determined to take up his abode, and pitched upon a small woody islet in the middle of a fresh pond as a safe place to build a fort.

A little to the northward of this large island lay a small one, half a mile in compass, and full of cedars. This he called Hill’s Hap.

On the opposite northern shore appeared another and similar elevation, to which he gave the name of Hap’s Hill.

By this description of the coast, it is evident that the sound into which Gosnold had now entered was Buzzard’s Bay.

The island on which Gosnold and his company took up their abode was Cuttyhunk.

Whilst some of Gosnold’s men labored in building a fort and storehouse on the small island in the pond, and a flat-boat to go to it, he crossed the bay in his vessel, and discovered the mouths of two rivers: one was that near which lay Hap’s Hill, and the other that on the shore of which New Bedford now stands.

After five days’ absence, Gosnold returned to the island, and was received by his people with great ceremony, on account of an Indian chief, who, with fifty of his men, was there on a visit.

To this chief they presented a straw hat and two knives; the hat he little regarded, but the knives he highly valued.

They feasted these savages with fish and mustard, and diverted themselves with the effect of the mustard on their noses.

These Indians were occasional visitants at the island, for the purpose of procuring shell-fish.

Four of them remained, after the others were gone, and helped Gosnold’s men to dig the roots of sassafras, with which, as well as furs bought of the Indians, the vessel was loaded.

After spending three weeks in preparing a storehouse, when they came to divide their provision, there was not enough to victual the ship and to subsist the planters till the ship’s return.

Some jealousy also arose about the intentions of those who were going back; and after five days’ consultation, they determined to give up their design of planting, and return to England.

On the 18th of June, therefore, Gosnold sailed out of the bay through the same passage by which he had entered it, and arrived at Exmouth, England, July 23.

Gosnold’s intention was to have remained, with a part of his men, and to have sent Gilbert, who was second in command, back to England, for further supplies.

After his return, he was indefatigable in behalf of settling colonies in America, and was one of those who embarked in the next expedition for Virginia, where he had the rank of counselor, and died in 1607.

=====

The Massachusetts State Quarter Coin shows with an image of the painting by Albert Bierstadt depicting Gosnold’s voyage and the Cuttyhunk island.