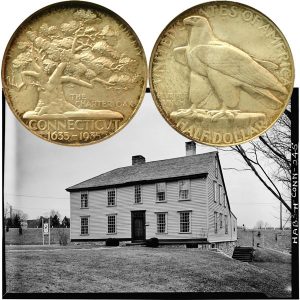

Today, the Connecticut Tercentenary Commemorative Silver Half Dollar Coin remembers the “ordinaries” from the early days of the colonies.

George Tongue obtained approval for his “ordinary” on September 1, 1656.

From the January 1922 Americana, American historical magazine by the National American Society, an excerpt of their article describing the “ordinaries,” taverns and inns of New London, Connecticut:

=====

In 1644, as shown by the Colonial Records of Connecticut, the General Court ordered “one sufficient inhabitant” in each town to keep an “ordinary,” since “strangers were straitened for lack of entertainment.”

In 1656, the General Court of Massachusetts made the towns liable to a fine for not sustaining an ordinary.

These houses of public entertainment were at first called “ordinaries,” probably ordinary, in the sense of common, and established by law.

The ordinary was under the supervision of the General Court and later of the town officers, and was hedged about with so many regulations and restrictions that the landlord of the present day would give up in despair.

The ordinary was usually a large house, with great fireplaces, and many rooms, and ample stable accommodations.

“Across the road the barns display

Their lines of stalls, their mows of hay.”

The better class had a parlor which was used as a sitting room for ladies, or was engaged by some dignitary for himself or family.

The most interesting as well as the most used room of the house was the taproom; its enormous fireplace, bare sanded floor, and ample settles and chairs, with a constant flow of visitors, combined to make a cheerful spot.

A tall rudely made writing desk served as a place for the landlord to cast up his accounts, and for the accommodation of the few guests who desired to write.

The bar itself was usually made with a sort of portcullis gate, which could be closed if desired.

While the bars remained until very recently in some of these old places, the old portcullis gate is rarely seen.

By the end of the Seventeenth Century the designation “ordinary” had passed into disuse, and “tavern” was the name by which the ordinary was known.

It was singular that the word “inn,” used in England, was not common in America; “inn” was a word of Anglo-Saxon origin, meaning house; while tavern was in France taverne, in Spain and Italy, taverna, while the Latin form, taberna, was also used, all derived from the Latin root, tab, hence tabula, a table.

In later days, the word tavern had fallen into disrepute, but formerly it denoted a highly respectable place, kept by a most worthy landlord.

As to the entertainment of these places, opinion differs.

In 1637, Lord Ley declined Governor Winthrop’s invitation to make his home at the Governor’s house, on the plea that he was so comfortably situated at the ordinary.

Hempstead, in his journey to Maryland in 1749, writes of being “handsomely entertained;” while Madam Sarah Knight, on her trip to New York, found the accommodations little to her liking, as she has fully informed us.

Each tavern was known by name, and some of these names are most interesting — the Blue Anchor, the Great House, the King’s Arms, the King’s Head, the Thistle and Crown, Rose and Thistle, Duke of Cumberland, St. George and the Dragon, the Red Lion, the Green Dragon, Dog’s Head in the Manger, the Fighting Cocks, the Black Horse, the Three Cranes, Bunch of Grapes, Plow and Harrow (one of the places where Hempstead stopped), are some of the names adopted.

The corruption of some names gave amusing signs — The Bag o’ Nails, from the “Bacchanalians,” this was a favorite name; the Cat and Wheel, from St. Catharine’s Wheel; the Goat and Compass, from “God Encompasseth Us;” Pig and Carrot, from the French pique et carreau; an English one was the Bull and Mouth, from the Boulogne Mouth or Harbor.

Before it became customary to name the streets and number the houses, at a time when comparatively few people were able to read or write, sign boards were a necessity, for the sign language is universal.

The signs were widely varied; some were painted or carved boards; and images — some carved from stone; modeled in terra-cotta or plaster; painted on tiles; wrought of various metals, and even stuffed animals were utilized.

Some of these old signs are still in existence; occasionally such a sign is noticed at some inn, whose landlord has recognized its value and drawing power in these days of antique hunting.

Such for example, is Ye Golden Spur, on the East Lyme trolley line; and the signboard bearing the Lion and the Unicorn, at the Windham Inn, on Windham Green.

More, however, are carefully preserved among the treasures of the historical societies.

In Salem, Massachusetts, in 1645, the law granted the landlord a license provided “there be sett upp some inoffensive sign obvious for direction to strangers.”

The Rhode Island Court in 1655 ordered that all persons appointed to keep an ordinary should “cause to be sett out a convenient Signe at ye most perspicuous place of ye said house, thereby to give notice to strangers yt it is a house of public entertainment, and this is to be done with all convenient speed.”

The signs were attached to wooden or iron arms extended from the tavern, or from a post or a nearby tree, or from a frame supported by two poles.

The Buck’s Horn Tavern in New York City had a pair of buck’s horns over the door.

Of the “Wayside Inn,” Longfellow wrote that “Half effaced by rain and shine, The Red Horse prances on the sign.”

In the library at Windham Green is preserved an image of Bacchus, carved from a piece of pine by British prisoners confined at Windham during the Revolutionary War, and bequeathed by them to Widow Cary, who kept a tavern on the Green.

Miss Larned says, “The comical Bacchus, with his dimpled cheeks and luscious fruits, was straightway hoisted above the tavern for a sign and figure-head, to the intense admiration and delight of all beholders.”

In the custody of the Connecticut Historical Society at Hartford is a signboard showing on one side the British coat-of-arms, and on the other side a full-rigged ship under full sail, flying the Union Jack; it has the letters “U A H,” and the date 1766.

This sign belonged to Uriah and Ann Hayden, who kept a tavern near the Connecticut river, in Essex, then the Pettapaug parish of Saybrook.

Bissell’s Tavern, at Bissell’s Ferry in East Windsor, Connecticut, had an elaborate sign depicting thirteen interlacing rings, and in the center of each was a tree or plant peculiar to the State designated, the whole surrounding a portrait of Washington.

It may be mentioned here, that during and after the War of the Revolution scarcely a town but had its Washington tavern, with varied Washington signboards; all names or signs relating to the King or to the British Kingdom were discarded, and as the Golden Lion changed into The Yellow Cat, so the other names underwent a similar change.

As has been said, the ordinaries were established by order of the General Courts at first, and later by the town authorities, who considered them as town offices, the appointment one of honor, and were therefore very particular to whom a license was granted.

A landlord was one of the best known men in town, influential, and possessed of considerable estate.

The first house of entertainment in Cambridge, Massachusetts, was kept by a deacon of the church, who was afterward made steward of Harvard College.

The first license to sell strong drink in that town was granted to Nicholas Danforth, a selectman and representative to the General Court.

In New London, Connecticut, on June 2, 1654, “Goodman Harries is chosen by the Towne ordinary keeper.”

The Goodman died the following November, and on the sixth of that month “John Elderkin was chosen Ordinary Keeper.”

“Widow Harris was granted by voat also to keep an ordinary if she will.”

On Foxen’s Hill, at the other end of the town, Humphrey Clay and his wife Catharine kept an ordinary till 1664.

In this same town, “At a General Town meeting September 1, 1656, George Tongue is chosen to keep an ordinary in the town of Pequot for the space of five years, who is to allow all inhabitants that live abroad the same privilege that strangers have, and all other inhabitants the like privilege except lodging. He is also to keep good order and sufficient accommodation according to Court Order being not to lay it down under six months warning, unto which I hereunto set my hand. (Signed) George Tonge.”

George Tongue bought a house and lot on the Bank, between the present Pearl and Tilley streets, and opened the house of entertainment which he kept during his lifetime and which being continued by his family, was the most noted inn of the town, for sixty years.

His daughter married Governor Winthrop, and after the Governor’s death his widow went to live in this house on the Bank, which she inherited from her parents.

In Norwich, on December 11, 1675, “Agreed and voted by ye town yt Sergent Thomas Waterman is desired to keepe the ordynary. And for his encouragement he is granted four ackers of paster land where he can convenyently find it ny about the valley going from his house into the woods.”

He was succeeded in 1690 by Deacon Simon Huntington.

Under date of December 18, 1694, “The towne makes choise of calib abell to keep ordinari or a house of entertaynment for this yeare or till another be choosen.”

In 1700, Thomas Leffingwell received a license, and this is supposed to have been the commencement of the famous Leffingwell Tavern, situated at the east corner of the town plot, and continued for more than a hundred years.

In 1706, Simon Huntington, Junr., and in 1709, Joseph Reynolds, were licensed.

On December 1, 1713, “Sergent “William Hide is chosen Taverner.”

Here is shown the change of name from “ordinary” to “tavern.”

Women sometimes kept the ordinary and tavern, as quoted in the case of Widow Harris and Widow Cary; some of the taverns kept by them became quite noted.

In 1714, Boston, with about ten thousand inhabitants, had thirty-four ordinaries, of which twelve were kept by women; four common victuallers, of whom one was a woman; forty-one retailers of liquors, seventeen of these being women; thus proving that women were accorded some rights and privileges in the early days.

=====

The Connecticut Tercentenary Commemorative Silver Half Dollar Coin shows with an image of the Leffingwell Inn, circa 1961.