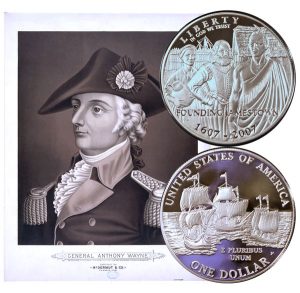

Today, the Jamestown Commemorative Silver Dollar Coin remembers when Lord Cornwallis visited the area 236 years ago.

Lord Cornwallis did not lose as many men, however the bravery of the Americans perhaps changed his strategy and could have began his downfall.

From the Battles of the United States, By Sea and Land by Henry Barton Dawson, published in 1858:

=====

The Action at Jamestown Ford, VA, July 6, 1781

General Cornwallis having reached Williamsburg, as related in a former chapter, preparations were made for his passage over the James River; and General Lafayette, waiting his motions, remained at Tyre’s plantation.

In accordance with the plan of operations which he had adopted, Lord Cornwallis moved from Williamsburg on the fourth of July; and on the evening of the same day, the Queen’s Rangers, under Lieutenant-colonel Simcoe, passed the river for the purpose of covering the passage of the baggage.

On the fifth and sixth of July the passage of the baggage and bat-horses was continued; and the seventh was the time which had been assigned for the passage of the main body of the army.

The intentions of the enemy were properly understood by General Lafayette; the principal difficulty which he experienced being in the means to be employed for securing correct information of the enemy’s movements.

In this he was opposed, chiefly, by the character of the maneuvers of Lord Cornwallis, who, penetrating the purposes of General Lafayette, so concealed his own, that the latter was kept in perfect ignorance of the details of the movements of his adversary, while he supposed that every feature was fully understood.

The design of General Lafayette was to wait until the greater part of the enemy had passed the river, and then to fall on the rear of that portion which remained, while its numbers or means of defense were not sufficient to secure it from his assault.

With this design he moved from Tyre’s, and, on the evening of the fifth of July he encamped within eight or nine miles of the enemy.

On the next morning, supposing the proper time had come for his intended blow, he prepared for the assault; and, notwithstanding intelligence was brought by Lieutenant-colonel Mercer, from Greenspring, that the main body had not yet crossed the river, he pressed forward to that place, reaching it within a few minutes after Lord Cornwallis had left it and moved towards the ford.

So perfect, indeed, had Lord Cornwallis perfected his plans, that General Lafayette discredited the report of Lieutenant-colonel Mercer; and this, added to the anxiety to fight, which the army evinced, induced him to abandon his usual caution, and attack the enemy.

The ground, in front of Greenspring, between the mansion and the Williamsburg road, is low and wet, forming a morass, about a quarter of a mile in width, and passable only by a narrow causeway of logs.

Over this causeway the enemy had gradually withdrawn; and the same narrow pathway afforded the only way by which General Lafayette could pursue him.

“Sage and experienced” as he was, Lord Cornwallis rejoiced that his adversary was giving way to the rashness of youth; and “his measures were taken to encourage the adventurous spirit, with the resolution , of turning it to his own advantage.”

His troops, both on the line of march and in camp, were kept as compact as possible; and orders were given, in case of an attack, that his pickets should fall back with the appearance of alarm and confusion, for the purpose of leading on the assailants.

At length, about three o’clock in the afternoon, General Lafayette moved from Greenspring, in pursuit of what he supposed to have been the rear of the British army.

A small party of dragoons, followed by the rifles, commanded by Majors Call and Willis, led the way over the causeway, and halted in a wood near the Williamsburg road.

The cavalry of Colonel Armand and Lieutenant-colonel Mercer’s commands, led by Major McPherson, followed next; and they were supported by the Pennsylvania line, led by the fearless General Wayne.

The Baron Steuben, with the militia, remained at Greenspring, as a reserve; but the distance between the two bodies, and the intervening causeway, neutralized the benefit which such a body might, reasonably, be expected to afford.

After the main body had crossed the causeway the riflemen were thrown upon the flanks, while the cavalry continued to move in advance of the column.

In this order the advance had not moved more than a mile when, about sunset, it was thrown back by a heavy fire from the enemy’s Yagers; when Lieutenant-colonel Mercer and Major McPherson were directed to leave the cavalry and take command of the riflemen—the former, those on the right; the latter, those on the left.

With these the enemy’s pickets were again attacked and driven back, with considerable loss, on his horse, which had been formed in an open field, about three- hundred yards in the rear.

At this moment the American cavalry came up and joined the riflemen,—that commanded by Colonel Armand supporting Major McPherson; that of the Virginia establishment supporting Lieutenant-colonel Mercer,—but the latter, made more bold by their supposed advantage, pushed forward, and formed in a ditch, under cover of a rail-fence, from which they renewed their fire, on what now showed itself to be the main body of the British army.

They were joined, soon afterwards, by Majors Willis and Galvan, with two battalions of Continental troops (light infantry), and by Captain Savage, with two field-pieces, all of whom joined in the engagement, and opened their fire on the enemy’s line.

When the American artillery opened its fire, it is probable Lord Cornwallis supposed the time had come when he should strike the fatal blow; and his line, in order of battle, moved against the Americans.

His right wing,—composed of the splendid brigade of veterans, which Lieutenant-colonel Webster had commanded throughout the earlier part of the campaign, embracing the Twenty-third, Thirty-third, and Seventy-first regiments, and the light troops, the brigade of the Guards, the Hessians, two battalions of light-infantry, and three field pieces,—led by Lieutenant colonel Yorke, encountering the party led by Major McPherson; while his left,—composed of the Forty-third, Seventy-sixth, and Eightieth regiments, supported by the cavalry of the Legion, and the light companies,—led by Lieutenant-colonel Dundas, encountered Lieutenant-colonel Mercer.

This formidable array of troops moved against the riflemen, in their position behind the rail-fence; but the latter, supported by the cavalry and the Continentals, received them with perfect coolness, and “the conflict was keenly maintained for some minutes.”

The force of numbers, however, compelled the Americans to fall back; and the enemy, animated with the prospect of an easy victory, rushed forward in pursuit.

A short distance in the rear of the first line, but, to some extent, concealed from the enemy by a dense wood, General Anthony Wayne—the hero of Stony Point—was holding a select body of about five hundred Pennsylvania troops in readiness for action.

When the light troops, in front, fell back, and revealed the unpleasant fact, that, instead of meeting a rear-guard, the main body of the British army,—a body of veterans,—led by Lord Cornwallis in person, was moving against him, all the peculiar characteristics of General Wayne’s character were displayed.

The sword and the bayonet were the favorite companions of that distinguished officer;—he rather gloried in their companionship, than sought to avoid their acquaintance,—and when the formidable array, which was moving down upon him, and the scattered fragments of his light-troops came in sight, he disdained to retreat before he had crossed his steel with that of the enemy.

With a degree of cool, determined resolution, which has scarcely a parallel in history, he awaited the approach of the enemy’s left wing,—the right being engaged in the pursuit of the light troops,—and when it had nearly reached him,—far outflanking him, both to the right and the left, he ordered his men to charge with the bayonet, and dashed against the line, with his usual impetuosity.

The three regiments whom he had assailed, not less than their distinguished commander-in-chief, were astonished at this unexpected attack; nor was their surprise diminished, when, after sustaining an action, with great spirit, for several minutes, the audacious assailant coolly withdrew his men, and retired about half a mile, where he joined his light troops, and passed over the causeway to Greenspring in safety.

The novelty of the last movement, and the unsurpassed bravery with which it was executed, appear to have changed the plan of operations which Lord Cornwallis had adopted; and probably supposing it was designed as a stratagem to draw him into an ambuscade, he made no attempt at pursuit; but allowed the Americans to withdraw to Greenspring without interference, and crossed over to Jamestown Island before morning, with every appearance of undesired haste.

The loss of the Americans, in this action, exclusive of that of the riflemen, which was not ascertained, was one hundred and eighteen men, killed, wounded, and missing; that of the enemy is said to have been about seventy-five.

=====

The Jamestown Commemorative Silver Dollar Coin shows with an image of General Anthony Wayne, circa 1878.