Today, the Texas Centennial Commemorative Silver Half Dollar Coin remembers a letter written by Stephen F. Austin on December 22, 1835 during their struggles for independence.

Perhaps by miscommunication or through intentional misleading information, Austin believed Texas should remain part of Mexico.

But, after spending time “across the border” in New Orleans, he quickly changed his position.

From the Life and Times of Henry Smith, The First American Governor of Texas by John Henry Brown, published in 1887:

=====

IMPORTANT LETTER FROM STEPHEN F. AUSTIN.

On the 31st of December, 1835, the following letter, addressed to certain persons named, some of whom were not members of the council, was read, but not printed in the journals. The original letter, now before us, is endorsed by E. M Pease, Secretary: “Referred to committee on State and judiciary, December 31, 1835.”

It will be remembered that Stephen F. Austin, Branch T. Archer and William H. Wharton, had been appointed, by the consultation on the 12th day of November, commissioners to seek aid for Texas in the United States.

This letter, as shown on its face, was written by Gen. Austin on the eve of their departure on that mission. Here it is:

Quintana, December 22, 1835.

Dear Sirs. — We expect to get off to-morrow in the Wm. Robbins, Archer, the two Whartons and myself and several other passengers.

There has been a great deal of low intrigue in the political maneuvering of a party who I am at last forced to believe have their own personal ambition and aggrandizement in view, more than the good of the country.

These men have operated on Archer until they have made him almost a political fanatic, preaching a crusade in favor of liberty against the city of Mexico, the only place short of which the army of Texas ought to stop, &c.

The Mexicans say that it is rather curious that the people of Texas should fight against military rulers, and at the same time, try to build up an army that may, in its turn, rule Texas as it pleases. I think it probable there will be some thousands of volunteers from the United States in a few months. They nearly all wish to join the regular army on the basis of volunteers.

What shall we do with so many? How support them? I fear that the true secret of the efforts to declare independence is, that there must then be a considerable standing army, which, in the hands of a few, would dispose of the old settlers and their interests as they thought proper.

The true policy for Texas is to call a convention, amend the declaration of the 7th of November last, by declaring Texas a State of the Mexican Confederacy under the basis laid down in the fifth and other articles of said declaration of 7th of November — form a constitution and organize a permanent government.

Every possible aid should be given to the Federal party in the interior; but it should be done as auxiliary aid, in conformity with the second article of the declaration.

By doing this the war will be kept out of Texas. This country will remain at peace. It will fill up rapidly with families, and there will be no great need of a standing army.

I believe that the combinations in the State of Tamaulipas are very extensive to form a new republic by a line from Tampico, west to the Pacific, and it is probable that the capitulation at Bexar was male to promote that object.

In short, it is much easier to keep the war out of Texas, than to bring it back again to our own doors. All that is necessary is for us not to do anything that will compel the Federal party to turn against us, and if they call on us for aid, let it be given as auxiliary aid, and on no other footing.

This takes away the character of a national war, which the government in Mexico is trying to give it, and it will also give to Texas just claims on the Federal party, for remuneration out of the proceeds of the Custom Houses of Matamoros and Tampico, for our expenses in furnishing the auxiliary aid.

But if Texas sends an invading force of foreign troops against Matamoros, it will change the whole matter. Gen. Mexia ought to have commanded the expedition to Matamoros and only waited to be asked by the Provisional Government to do so.

I repeat: It is much easier to keep the war out of Texas and beyond the Rio Grande, than to bring it here to our own doors. The farmers and substantial men of Texas can yet save themselves, but to do so they must act in union and as one man.

This, I fear, is impossible. In the upper settlement Dr. Hoxey is loud for independence. Of course he is in favor of a large standing army to sustain it, and will no doubt be ready to give up half or all of his property to support thousands of volunteers, etc., who will flood the country from abroad.

It is all very well and right to show to the world that Texas has just and equitable grounds to declare independence; but it is putting the old settlers in great danger to make any such declaration, for it will turn all the parties in Mexico against us. It will bring back the war to our doors, which is now far from us, and it will compel the men of property in Texas to give up half or all to support a standing army of sufficient magnitude, to contend with all Mexico united.

Yours respectfully, S. F. Austin.

To Messrs. F. W. Johnson, Daniel Parker, D. C. Barrett, J. W. Robinson, Wyatt Hanks, P. Sublett and Asa Hoxey.

P. S. Mr. Parker will please send this letter to T. J. Rusk, of the Nacogdoches department. S. F. A.

This letter from Gen. Austin, considering the time and the peculiar circumstances under which it was written — the time being the eve of his departure on a momentous mission; the circumstances being that he differed with the chief executive of the country, his two colleagues, Wharton and Archer, and with a rapidly growing public sentiment in favor of absolute independence from Mexico, will appear to many as extraordinary and ill-timed.

And when his New Orleans letter to Gen. Houston, written only sixteen days later, is read, unless a satisfactory explanation can be given, astonishment must be the result.

One of its effects was to increase the alienation between Governor Smith, the head of the Independence party, and a majority of the council who agreed with Gen. Austin.

But, rightly understood, it was in harmony with all the utterances of that gentleman, from his first Mexican letter, from Matamoros, May 30th, 1833, followed by others from the City of Mexico down to and after his return to Texas in September, 1835.

That Gen. Austin’s heart and interest were deeply involved in the welfare of Texas, must be evident to every mind comprehending his true position.

But it must be borne in mind that he went to Mexico in May, 1833, as the agent of Texas, to secure her admission into the Mexican Union as a distinct State, separate from Coahuila, under the constitution drafted by the convention of April in that year, which selected him as one of three commissioners to represent them at the Mexican Capitol, and that he alone undertook the journey; that he remained in Mexico two years and three months and during most of that time was incarcerated in the prisons of the Capitol — denied, much of the time, intercourse with his friends and rarely hearing from Texas, and then in meager and unreliable rumors — and that he had no reliable means of knowing the truth in regard to the rapidly changing events, either in Texas or Mexico.

…

It will be seen that he continued to cherish the views he brought from Mexico and seems not to have grasped the real condition of affairs in Texas, or from a Texas stand point, but rather to have been misled by those who believed in fighting for statehood as an integral part of Mexico and who were opposed to independence.

But a very short stay in New Orleans opened to his mind a new line of thought, in favor of the policy he had before opposed and largely for reasons that had been urged by Governor Smith, Wharton, Archer, Travis and others. This cogent reason was, that while fighting in internecine strife as a mere province of Mexico, Texas need expect no material aid from the United States; but, on the other hand, if Texas would declare herself an Independent Republic, men, money and munitions of war would pour in upon her from the great Republic to which nineteen-twentieths of the Texas people owed their birth.

From that moment Stephen F. Austin was an ardent friend and advocate of independence. He rendered valuable service in the United States; returned home in June, became the first Secretary of State ofhte Republic on the 23rd of October, and died on the 27th of December, 1836, lamented by all as the founder and father of American civilization in Texas.

=====

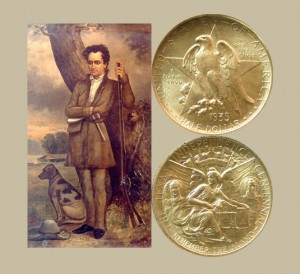

The Texas Centennial Commemorative Silver Half Dollar Coin shows with an artist’s image of Stephen F. Austin, circa 1833.