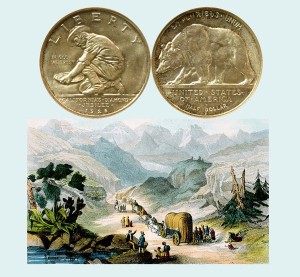

Today, the California Diamond Jubilee Commemorative Silver Half Dollar Coin remembers the first emigrant wagon train to arrive in California 175 years ago.

In The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine of November 1890, one of the party gave his account of the trip.

An excerpt of the last days before reaching their destination:

=====

We were now in what is at present Nevada, and probably within forty miles of the present boundary of California. We ascended the mountains on the north side of Walker River to the summit, and then struck a stream running west which proved to be the extreme source of the Stanislaus River.

We followed it down for several days and finally came to where a branch ran into it, each forming a cañon. The main river flowed in a precipitous gorge in places apparently a mile deep, and the gorge that came into it was but little less formidable.

At night we found ourselves on the extreme point of the promontory between the two, very tired, and with neither grass nor water. We had to stay there that night.

Early the next morning two men went down to see if it would be possible to get through down the smaller cañon.

I was one of them, Jimmy John the other. Benjamin Kelsey, who had shown himself expert in finding the way, was now, without any election, still recognized as leader, as he had been during the absence of Bartleson.

A party also went back to see how far we should have to go around before we could pass over the tributary cañon.

The understanding was, that when we went down the cañon if it was practicable to get through we were to fire a gun so that all could follow; but if not, we were not to fire, even if we saw game.

When Jimmy and I got down about three-quarters of a mile I came to the conclusion that it was impossible to get through, and said to him, “Jimmy, we might as well go back; we can’t go here.”

“Yes, we can,” said he ; and insisting that we could, he pulled out a pistol and fired.

It was an old dragoon pistol, and reverberated like a cannon. I hurried back to tell the company not to come down, but before I reached them the captain and his party had started.

I explained, and warned them that they could not get down; but they went on as far as they could go, and then were obliged to stay all day and night to rest the animals, and had to go about among the rocks and pick a little grass for them, and go down to the stream through a terrible place in the cañon to bring water up in cups and camp-kettles, and some of the men in their boots, to pour down the animals’ throats in order to keep them from perishing.

Finally, four of them pulling and four of them pushing a mule, they managed to get them up one by one, and then carried all the things up again on their backs — not an easy job for exhausted men.

In some way, nobody knows how, Jimmy got through that cañon and into the Sacramento Valley. He had a horse with him—an Indian horse that was bought in the Rocky Mountains, and which could come as near climbing a tree as any horse I ever knew.

Jimmy was a character. Of all men I have ever known I think he was the most fearless; he had the bravery of a bulldog.

He was not seen for two months—until he was found at Sutter’s, afterwards known as Sutter’s Fort, now Sacramento City.

We went on, traveling west as near as we could.

When we killed our last ox, we shot and ate crows or anything we could kill, and one man shot a wild-cat. We could eat anything.

One day in the morning I went ahead, on foot of course, to see if I could kill something, it being understood that the company would keep on as near west as possible and find a practicable road.

I followed an Indian trail down into the cañon, meeting many Indians on the way up. They did not molest me, but I did not quite like their looks.

I went about ten miles down the cañon, and then began to think it time to strike north to intersect the trail of the company going west. A most difficult time I had scaling the precipice.

Once I threw my gun up ahead of me, being unable to hold it and climb, and then was in despair lest I could not get up where it was, but finally I did barely manage to do so, and made my way north.

As the darkness came on I was obliged to look down and feel with my feet lest I should pass over the trail of the party without seeing it.

Just at dark I came to an enormous fallen tree and tried to go around the top, but the place was too brushy, so I went around the butt, which seemed to me to be about twenty or twenty five feet above my head.

This I suppose to have been one of the fallen trees in the Calaveras Grove of Sequoia gigantea or mammoth trees, as I have since been there, and to my own satisfaction identified the lay of the land and the tree.

Hence I concluded that I must have been the first white man who ever saw the Sequoia gigantea, of which I told Frémont when he came to California in 1844.

Of course sleep was impossible, for I had neither blanket nor coat, and burned or froze alternately as I turned from one side to the other before the small fire which I had built, until morning, when I started eastward to intersect the trail, thinking the company had turned north.

But I traveled until noon and found no trail; then striking south, I came to the camp which I had left the previous morning.

The party had gone, but not where they had said they would go; for they had taken the same trail I had followed, into the cañon, and had gone up the south side, which they had found so steep that many of the poor animals could not climb it and had to be left.

When I arrived the Indians were there cutting the horses to pieces and carrying off the meat. My situation, alone among strange Indians killing our poor horses, was by no means comfortable.

Afterward we found that these Indians were always at war with the Californians.

They were known as the Horse Thief Indians, and lived chiefly on horse flesh; they had been in the habit of raiding the ranches even to the very coast, driving away horses by the hundreds into the mountains to eat.

That night after dark I overtook the party in camp. A day or two later we came to a place where there was a great quantity of horse bones, and we did not know what it meant; we thought that an army must have perished there.

They were of course horses that the Indians had driven in there and slaughtered. A few nights later, fearing depredations, we concluded to stand guard—all but one man, who would not. So we let his two horses roam where they pleased. In the morning they could not be found.

A few miles away we came to a village; the Indians had fled, but we found the horses killed and some of the meat roasting on a fire.

We were now on the edge of the San Joaquin Valley, but we did not even know that we were in California.

We could see a range of mountains lying to the west, the Coast Range, but we could see no valley.

The evening of the day we started down into the valley we were very tired, and when night came our party was strung along for three or four miles, and every man slept right where darkness overtook him.

He would take off his saddle for a pillow and turn his horse or mule loose, if he had one. His animal would be too poor to walk away, and in the morning he would find him, usually within fifty feet.

The jaded horses nearly perished with hunger and fatigue.

When we overtook the foremost of the party the next morning we found they had come to a pond of water, and one of them had killed a fat coyote; when I came up it was all eaten except the lights and the windpipe, on which I made my breakfast.

From that camp we saw timber to the north of us, evidently bordering a stream running west. It turned out to be the stream that we had followed down in the mountains — the Stanislaus River.

As soon as we came in sight of the bottom land of the stream we saw an abundance of antelopes and sandhill cranes. We killed two of each the first evening.

Wild grapes also abounded. The next day we killed thirteen deer and antelopes, jerked the meat and got ready to go on, all except the captain’s mess of seven or eight, who decided to stay there and lay in meat enough to last them into California!

We were really almost down to tidewater, but did not know it.

Some thought it was five hundred miles yet to California. But all thought we had to cross at least that range of mountains in sight to the west before entering the promised land, and how many more beyond no one could tell.

Nearly all thought it best to press on lest the snows might overtake us in the mountains before us, as they had already nearly done on the mountains behind us (the Sierra Nevada).

It was now about the first of November. Our party set forth bearing northwest, aiming for a seeming gap north of a high mountain in the chain to the west of us.

That mountain we found to be Mount Diablo. At night the Indians attacked the captain’s camp and stole all their animals, which were the best in the company, and the next day the men had to overtake us with just what they could carry in their hands.

The next day, judging by the timber we saw, we concluded there was a river to the west. So two men went ahead to see if they could find a trail or a crossing.

The timber seen proved to be along what is now known as the San Joaquin River. We sent two men on ahead to spy out the country.

At night one of them returned, saying they had come across an Indian on horseback without a saddle who wore a cloth jacket but no other clothing.

From what they could understand the Indian knew Dr. Marsh and had offered to guide them to his place.

He plainly said “Marsh,” and of course we supposed it was the Dr. Marsh before referred to who had written the letter to a friend in Jackson County, Missouri, and so it proved.

One man went with the Indian to Marsh’s ranch and the other came back to tell us what he had done, with the suggestion that we should go on and cross the river (San Joaquin) at the place to which the trail was leading.

In that way we found ourselves two days later at Dr. Marsh’s ranch, and there we learned that we were really in California and our journey at an end.

After six months we had now arrived at the first settlement in California, November 4, 1841.

The account of our reception, and of my own experiences in California in the pastoral period before the gold discovery, I must reserve for another paper. — John Bidwell.

=====

The California Diamond Jubilee Commemorative Silver Half Dollar Coin shows with an artist’s image of wagon train, circa 1850.