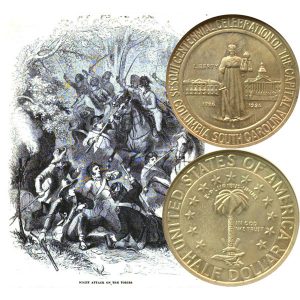

Today, the South Carolina Commemorative Silver Half Dollar Coin remembers the efforts of General Francis Marion in September 1780.

Francis Shallus wrote in his Chronological Tables for Every Day of the Year, Volume 2, published in 1817:

=====

September 4, 1780

American general Marion with 53 men surprised a party of 45 Tories and killed and wounded all but 15 who escaped, he then met and defeated the main body of them, about 200, whom he also put to flight.

=====

In the Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Volume 17, published in 1858, Benson John Lossing’s article about Francis Marion described the efforts:

=====

Who were the men that composed Marion’s famous Brigade? They were inhabitants of an isolated district in the interior of South Carolina, where British soldiery had not yet trodden.

They were willing to be loyal, while loyalty was consistent with honor and justice. They had not taken up arms, and were willing to remain quiet. But when the British commanders, faithless to the terms of the capitulation at Charleston, seized many of the best citizens there, and without provocation sent them to the loathsome prisons of St. Augustine, and then called upon the inhabitants to take up arms for the King, the people of Williamsburg district were among the first to resent the insult.

Their character may be well understood by an event related by Simms, in which their chosen representative was chief actor. Major John James had been sent by them to the Provincial Congress, and when the proclamation calling upon the people to arms for the crown appeared, he was in command of them as State Militia.

In this double capacity he visited Georgetown for information concerning the requirements of the proclamation. That post was then in possession of the British, and was commanded by Ardesoif, captain of a vessel which lay at anchor in the river nearby.

James was attired as a plain back woodsman, and Ardesoif was disposed to treat him with disdain. The patriot pressed his questions earnestly; and when he peremptorily demanded of the official what were the terms of submission, the haughty Briton replied, “Unconditional. His Majesty offers you a free pardon, of which you are undeserving, for you all ought to be hanged; but it is only on condition that you take up arms in his cause.”

“The people whom I come to represent will scarcely submit on such conditions, ” James replied.

“Represent!” exclaimed Ardesoif, in a rage; “you accursed rebel, if you dare speak in such language I will have you hung up at the yard-arm!”

Ardesoif was armed; James had no weapon: but before the insolent official could draw his sword the patriot seized the chair on which he had been sitting and with one blow floored him.

In a moment afterward James was in his saddle, and before pursuit could be attempted had escaped to the woods.

The people of his district gathered around him, and his story kindled a deeper hatred of British rule. They formed themselves into military companies under tried commanders, and then invited Marion to become their chief.

As we have seen, he was then in the camp of Gates, on the borders of North Carolina. They did not await his arrival to commence active operations, for rumor reported that the fiery Tarleton, who had heard of the rebellious gatherings in the Williamsburg district, was already rapidly approaching their domain.

Tarleton’s cruelties elsewhere had aroused the fiercest indignation throughout the Black River region, and under the general command of Captain M ‘Cottry, a large number of the Williamsburg people gathered on the banks of Lynch’s Creek to repel invasion.

There, four days before the signal defeat of Gates, near Camden, occurred, Marion took formal command of his Brigade, and among the interminable swamps of Snow’s Island, near the junction of Lynch’s Creek with the Great Pedee, he made his chief rendezvous during a greater portion of his independent partisan warfare.

Marion was now in the prime of life, having seen eight-and-forty summers. He was lean and swarthy, rather below the middle height of men, with a body well set upon awkward limbs.

His countenance was pleasing, and was lighted up by piercing black eyes, over which arched a high, intellectual forehead.

He wore a close “roundabout” jacket of coarse crimson cloth, and upon his head was the same cap, and silver crescent, and stirring words which marked him as the recruiting officer in that region five years before.

He was a stranger, personally, to most of those who then greeted him as their commander, but an invisible link of sympathy united the chief and his men at once.

His greater deeds were yet to be performed, but in all hearts there was a sure prophecy of his achievements.

Marion’s first expedition, after taking command, was against a large body of Tories under Major Gainey, an active British officer, who were encamped on Britton’s Neck, between the Great and Little Pedee.

Unsuspicious of danger, the usually vigilant Gainey was not prepared for a sudden attack.

Marion fell upon his camp just at dawn. A captain and several privates were killed, and Gainey mounted his horse and fled, closely pursued by Major James, the assailant of Captain Ardesoif.

Intent upon his game, James did not see the gathering Tories ahead until he was too near to retreat with safety. His rare presence of mind saved him.

Waving his sword aloft, he shouted, as if to a host of men, “Come on, boys; here they are!” and dashing forward he so frightened the Tories that they fled and sought safety in the dark swamps on the Pedee.

In this attack Marion did not lose a comrade, and had only two slightly wounded.

The followers of Marion were greatly elated by this success.

He did not allow their enthusiasm to abate by inaction, and within twenty- four hours afterward he was making a wide circuit to fall upon a Tory camp, under Captain Barfield, a few miles distant.

That officer was on the alert, and Marion resorted to stratagem.

He ambushed some picked men, and then, after showing himself to Barfield, feigned a retreat, and drew his antagonist into pursuit.

The Tories fell into the snare, and were scattered to the winds by the men in ambush.

This victory was more complete than the one over Gainey; and these successes, so sudden and thorough, inspired Marion’s followers with the greatest confidence in their commander and reliance upon themselves.

This was a great point gained at the outset for the partisan, and in that confidence and self-reliance was one of the chief elements of his success.

When Marion left the camp of Gates that general commissioned him to destroy the boats on the rivers of the lower country, so as to impede the progress of the British toward the interior, and to “annoy the enemy.”

Marion was doing more, far more; yet he was not neglectful of his superior’s orders.

Notwithstanding the heats of August were intense, and the cool shades of the cypress swamps were grateful, he did not relax his activity; and on the day succeeding Gates’s defeat he divided his brigade for wider service.

Intelligence of that disaster had not yet reached him, and with the smaller portion of his force he marched toward the Upper Santee, while four companies, under Colonel Peter Horry, were dispatched to the performance of the special service ordered by Gates, and to procure powder and balls, if possible.

These supplies were greatly needed. So scarce was ammunition within the field of Marion’s control that his men frequently went into action with only three or four cartridges apiece.

On the evening after leaving Horry, Marion approached Nelson’s Ferry, a short distance from Eutaw Springs, and the principal crossing-place of the Santee for travelers and troops passing between Charleston and Camden. While on the march he was informed of the defeat of Gates, but he withheld the sad intelligence from his men, fearing it might depress their spirits.

The concealment was brief, for that night his scouts brought word of the approach of a strong British guard, with a large body of prisoners from Gates’s army. Marion instantly resolved upon a daring enterprise, unmindful of the weakness of his force; and a little past midnight Colonel Hugh Horry was sent, with sixteen men, to take possession of the only road through the swamp to the Santee.

Then, at the head of the main body, Marion stealthily crept toward the camp of the British escort, and just at dawn he suddenly appeared in their midst.

The surprise and victory were instant and complete.

Not one of Marion’s men was lost, while twenty-four of the regulars and Tories were killed or made prisoners, and one hundred and fifty captives of the Maryland Continental Line were released.

Their liberator offered to incorporate them into his brigade, but only three accepted his invitation!

The disasters of the 16th of August had utterly crushed their spirits, and they saw no political future for the colonies, as independent States.

The cause of the patriots did, indeed, seem hopeless.

Two armies, under commanders of acknowledged skill, had been annihilated within the space of three months; Tarleton had struck Buford and Sumter almost exterminating blows near the banks of the Catawba, and the small corps of Marion was the only organized body of Republicans in open hostility to the crown below the Roanoke.

Had the British commanders been wise enough then to have discovered the expediency of a gentle, conciliating policy, the spirit of rebellion might have been soothed into inaction, and the subjugation of the South become a permanent result.

But the sentiment of military tyranny of an earlier and ruder age prevailed.

Multiplied cruelties and oppressions goaded the people to madness and resistance, and the arm of Marion was everywhere strengthened by their encouragement.

The British feared and hated him; and Tarleton and Wemyss, two of the most active cavalry officers of the Southern British army, were specially instructed by Cornwallis to catch the “Swamp Fox,” if possible.

And now, for the first time, the Williamsburg district suffered invasion.

Wemyss took the lead in pursuing Marion; and from the Upper Santee to the Black River, and beyond, even to the banks of the Great Pedee, he followed the partisan with hound-like pertinacity, while a band of Tories, ever intent upon plunder, hung upon his rear to get the jackal’s share of the carcass of Whig possessions.

Never was a military service so peculiar as that in Marion’s Brigade.

His force was continually fluctuating, for all were volunteers on call. Some with him today would be far away tomorrow, hurrying their families to places of safety, or moving their property from the invader’s track.

There was a necessity for this, for plunder and conflagration marked the progress of Wemyss and his Tory associates.

Marion always yielded to the earnest wishes of his men, when they asked for a day or week to look after family or property.

This indulgence made them prompt in duty and faithful in the fulfillment of promises. A desertion was rare; and a soldier seldom remained away longer than his specified furlough.

It was this peculiarity of the service that caused the invasion of Wemyss to make a great draft upon the strength of Marion’s Brigade, for all homes were endangered, either by the march of the invader or the rapacity of resident Tories, made bold by the presence of British power.

In his retreat the partisan seldom had more than eighty followers at a time; and when at Drowning Creek, on the last day of August, he made his first halt, and sent back scouts to obtain intelligence, he had only sixty men to follow him into North Carolina.

Saddened, but not disheartened, he pressed onward, and sat down at White Marsh, not far from the beautiful banks of Lake Waccamaw, to await the return of scouts sent back from time to time during his flight.

Marion had rested but a day when intelligence came that Wemyss had relinquished pursuit, and had retired to Georgetown.

The partisan leaped into his saddle, and twenty hours afterward he and his followers had retraced their steps sixty miles through the Tory settlements on the Little Pedee, and halted on South Carolina soil.

He found the people anxiously awaiting his return to lead them to avenge their wrongs. The path of Wemyss, seventy miles in length and fifteen in breadth, was a track of desolation. Sword, bayonet, and torch had been terribly active.

Plantations had been desolated by fire; cattle and sheep had been wantonly bayoneted in the fields; and scores of families were sheltered in the swamps.

The men gathered eagerly to the standard of their leader. Cruel wrongs gave strength to their arms, fleetness to their feet, power to their wills; and with the joy of desperate men intent on vengeance they followed Marion toward the Black Mingo Creek, fifteen miles distant, where a body of the hated Tories were encamped.

Stealthily as a tiger in the jungle Marion approached his foe. A mile above the Tory camp was a plank bridge across the deep stream, and over it he was obliged to pass.

The clatter of the horses’ hoofs startled the enemy, and an alarm-gun was fired.

Speed rather than caution was now necessary, and the partisan and his men pushed forward, at full gallop, to gunshot distance from the vigilant pickets.

There some dismounted, and at midnight Marion’s whole force fell upon the Tories at different points. The battle was brief and bloody.

Marion lost but one man, while the Tories were almost annihilated.

The few survivors fled to the Black Mingo Swamp for refuge; and Toryism in that region dwindled from its late giant proportions into the insignificance of a dwarf.

Wavering men came to a decision in the presence of the conqueror, and, with avowed Tories hitherto, joined his ranks.

He began to be called the Invincible; for he had never struck a blow without success, and throughout the whole low country his name was a terror to Tory and Regular.

=====

The South Carolina Commemorative Silver Dollar Coin shows with an artist’s image of a night attack on the Tories.