Today, the Fort Vancouver Commemorative Silver Half Dollar Coin remembers the passing of the bill forming the Washington Territory on March 2, 1853.

From the History of the State of Washington by Edmond Stephen Meany, published in 1909:

=====

It is clearly shown that the people in the northern counties of Oregon Territory, even though relatively few in number, were abundantly justified in their desire for a separate organization.

The area to be included in the new Territory was apparently determined by nature. The majestic sweep of the “River of the West” from its mouth to its intersection of the British line at the forty- ninth parallel embraced enough land to make a large, populous, and wealthy State.

The agitation took up this idea from the first. John Butler Chapman moved from Oregon to Grays Harbor in the winter of 1850-1851, and began what he called Chehalis City. His one-house “city” disgusted him. He moved to Puget Sound, settling at Steilacoom, and took immediate interest in the movement for a new government.

At the Fourth of July celebration in Olympia, in 1851, he was the orator. That oration is lost to history except in the surviving tradition that he aroused enthusiastic applause when he graphically pictured the grandeur of the proposed Territory and future State of Columbia.

Thus the great river contributed the name as well as the boundary. A petition was forwarded to Congress. The agitation was continued. Independence Day was again celebrated at Olympia.

This time the oration was delivered by a well-educated young lawyer, named Daniel R. Bigelow, who had arrived the previous November. While crossing the plains he had delivered a Fourth of July oration in 1851.

The effect of his Olympia oration is best shown by the treatment it received. To further the cause uppermost at the time, a newspaper was begun and named after the proposed Territory — The Columbian.

Though Mr. Bigelow had made no special plea for a division of Oregon, his eloquent oration was published in full more than two months after its delivery, in the first issue of that pioneer paper, September 11, 1852.

The following quotation will show the spirit applauded by those pioneers:

“We are now assembled on the verge of United States soil, — no monumental shafts erected on revolutionary battlefields meet our eyes to stimulate our patriotism and awaken our sympathies. We are far removed from all such scenes, farther than the most enthusiastic actors in those scenes ever expected the results of their labors to extend. But the scene exhibited here today shows that the great national heart sends its pulsations, actively, healthfully, patriotically even to this distant extremity. We see the flag of the Union waving over us, and we feel that beneath its ample folds we are at home.”

A convention was called to meet at the house of H. D. Huntington, known affectionately as “Uncle Darby,” in the town of Monticello near the mouth of Cowlitz River. The convention assembled on October 25, 1852, and adopted a memorial to Congress saying:

“The memorial of the undersigned, delegates of the citizens of Northern Oregon, in convention assembled, respectfully represent to your honorable bodies that it is the earnest desire of your petitioners, and of said citizens that all that portion of Oregon Territory lying north of the Columbia River and west of the great northern branch thereof, should be organized as a separate territory under the name and style of the Territory of Columbia.”

They then appended nine strong reasons and signed their names, forty-four in all. A copy of the memorial was sent to General Joseph Lane who was then Oregon’s delegate to Congress.

On November 4, the Oregon Legislature adopted a memorial asking for the division, but before this reached Washington City, Delegate Lane had acted on the Monticello document.

On the first day of the second session of the Thirty-second Congress, December 6, 1852, Mr. Lane, by suspension of the rules, introduced a resolution requesting the Committee on Territories to examine into the expediency of dividing Oregon Territory and reporting by bill or otherwise.

The bill was up for consideration by the House on February 8, 1853.

The contest, as shown by the Congressional Globe, was by no means a dull proceeding. Though President Millard Fillmore was a Whig, Congress was overwhelmingly Democratic in both branches. The Speaker was a Democrat, Linn Boyd of Kentucky. Delegate Lane was a Democrat.

The bill was afforded favorable consideration from the beginning, though obstacles were not wanting. Lane’s extended and forceful speech was several times interrupted by questioners, one of whom asked how many people were in the proposed new Territory.

This brought the retort: “The population of Columbia in that case will be quite as great as was that of the whole of Oregon at the period of its organization into a Territory.”

He indorsed the Monticello memorial as a part of his speech and closed his remarks with the following:

“That a single Territory of this Union should become a State embracing an area of over three hundred and forty-one thousand square miles, and commanding a range of sea-coast of over six hundred miles, is a proposition so utterly at variance with the interests of the country, and with every principle of right and justice, that I sincerely trust Oregon may not be the State so admitted into the Confederacy.”

Mr. Stanton, of Kentucky, said that as we already had a District of Columbia, he would like to see the name of this new Territory changed from Columbia to Washington. Mr. Lane said he would never object to that name.

Mr. Stanton then concluded: “I have nothing more to say, except that I desire to see, if I should live so long, at some future day, a sovereign State bearing the name of the Father of his Country. I therefore move to strike out the word ‘Columbia’ wherever it occurs in the bill, and to insert in lieu thereof the word ‘Washington.’ ”

Mr. Stanley, of North Carolina, said he hoped that motion would prevail.

There was something singular about the case. He had just been suggesting that identical change to his neighbor. The new name was adopted, but not without some opposition.

It was pointed out that the same name for the national capital and a State would tend to endless confusion in the transition of the mails. Some appropriate Indian name, it was suggested, would be better.

The contest was carried to the Senate, where Stephen A. Douglas, chairman of the committee on Territories, reported the bill favorably with an amendment. As time was short the amendment was withdrawn.

It was not printed, and only recently a search in the manuscript records of the Senate showed that the Douglas amendment did not favor an Indian name, but simply added two letters, making the suggested name “Washingtonia.”

The bill passed the Senate on March 2, 1853, and was signed by President Fillmore two days before his term of office expired.

The southern boundary had been changed during the consideration so as to run along the Columbia River to its intersection of the forty-sixth parallel of north latitude, near the mouth of the Walla Walla River, thence due east along that line to the summit of the Rocky Mountains.

By that change the area was about doubled. Another large addition was made when Oregon became a State, on February 14, 1859. Her eastern boundary was defined: “thence up the middle of the main channel of said river [Snake], to the mouth of the Owyhee River; thence south, to the parallel of forty-two degrees north.”

This left all of the present State of Idaho and portions of Montana and Wyoming attached to Washington until March 3, 1863, when Idaho Territory was organized, giving Washington its present eastern boundary.

…

=====

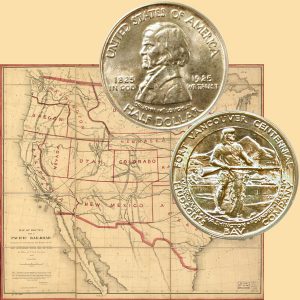

The Fort Vancouver Commemorative Silver Half Dollar Coin shows with a western territorial map, circa 1855.