Today, the North Dakota State Quarter Coin remembers the day, September 8, 1883, when a young Theodore Roosevelt stepped from the train in the western wilderness of what is now North Dakota.

In his book, Roosevelt’s Ranch Life in North Dakota, Albert Tangeman Vollweiler included descriptions of Mr. Roosevelt’s arrival and his efforts as a cattle rancher.

=====

It was into this region that Theodore Roosevelt came in September, 1883.

He had never been naturally robust and, therefore, by hard effort, he had learned while yet in his teens, to box, to ride, to shoot, and to stay out of doors with nature till he loved to do this.

After he had served several terms in the New York Assembly, when he was yet a slender young man of twenty-six, he came over the Northern Pacific for a hunting trip in the Little Missouri Valley.

When he arrived at the squalid shack town of Little Missouri on the west bank of the Little Missouri River, opposite which Medora was later built, he went to the rude hotel, taking his baggage along.

This consisted chiefly of a fine collection of rifles. One was an Express, inlaid with gold plates engraved with hunting scenes. The one he usually used, however, was a Winchester of 45-90 calibre.

The hotel was known as the Pyramid Park hotel. It was built of logs and was managed by E. H. Bly of Bismarck who made his living by cutting logs for ties and by boarding such men as came to Medora.

It was the only building at Medora besides the station. The entire upper floor of the hotel consisted of a room which contained fourteen beds, and Roosevelt occupied one of these.

The next day he met a ranchman, J. A. Ferris, who happened to be in town and, after a bargain had been made, the latter took him eight miles southward to his ranch, Chimney Butte.

Here the party outfitted and, with ponies, blankets, rifles, and food, proceeded fifty miles southward. They returned late in the fall after a successful hunt.

If this country supported such numbers of wild animals it would also support herds of cattle and so, before leaving, having been attracted by the health- giving life of a cattle ranch, Roosevelt purchased Chimney Butte Ranch.

This included the horses and cattle that were marked with a Maltese Cross on their left hips, a few rude buildings and corrals, together with grazing rights over the surrounding region.

Roosevelt retained the services of the former owners, Sylvane Ferris and A. W. Merrifield, to manage his new property.

Most good cowmen used a Texan breed of cattle because of their size and their ability to withstand the winter. This was especially true of experienced cowmen who came from the South.

Easterners usually made poorer stockmen unless they stayed long enough to learn the cattle business by experience.

Roosevelt labored under this handicap. The cattle business was new to him and to his foreman, Sylvane Ferris.

The latter had come from Canada and had previously hunted or worked on the Northern Pacific railroad.

The year following Roosevelt’s purchase of Chimney Butte, he had shipped in to his ranch many carloads of Minnesota dogie cattle.

They had no pride of ancestry, nor great size nor hardiness to withstand the winter. These things tended to preclude the possibility of making large profits.

Roosevelt never owned any land in North Dakota. The land of the government was used freely by all ranchmen before it was surveyed and homesteaders came.

Since there were no fences in the early stages of the ranching industry, the brand indicated the owner.

The region was well adapted for cattle raising. The buttes break the force of the winter winds and the clusters of plum and buffalo-berry bushes, ash, box-elder, elm, and cedar trees afford natural shelter for stock.

Grazing is good the year round, for the short nutritious grass ripens early. It thus escapes frosts and retains its food value and is as good as hay when obtained on exposed places in winter.

The region soon built up rapidly. Eastern capitalists invested their money and men of intelligence, sometimes with a college education, and hardy, trusty pioneers managed their ranches, while Texan cowboys came to work on them.

The latter formed the bulk of the population, so that the country west of the Missouri resembled the southwest more than the country east of the Missouri.

Soon the valleys held great herds of cattle that found there abundant food both summer and winter.

The cattle with the Maltese Cross brand now numbered about 3000. Eighty ponies were kept to help take care of them. Six men were employed in summer and three in winter.

Their wages were about $35 to $40 per month with “room” and board. The foreman, Sylvane Ferris, was financially interested in the undertaking.

In 1884 Roosevelt started a new ranch on untrodden ground at Elkhorn, also on the Little Missouri river, forty miles north of Chimney Butte.

Here he built a very substantial log cabin out of logs that were all squared. It was a much better cabin than the one at Chimney Butte and served as Roosevelt’s headquarters.

After he abandoned it, it was used as a lumber yard by the surrounding settlers.

In 1904, there were only a few logs left to mark the spot where it stood.

This ranch used an elkhorn and triangle for its brand and was managed by Sewall and Dow.

The largest number of cattle on Roosevelt’s two ranches at any one time was about 5,000.

They roamed from the Kildeer Mountains on the north to the Chalk Buttes on the south.

…

Young Roosevelt, like any new comer in the west, found people waiting for him to show what kind of a man he was.

Bull-whackers, buffalo-hunters, broncho-busters, cow-punchers, and mule-skinners stated that this new eastern dude would soon be returning home.

“Four-eyes,” one of them called him, because he committed the unpardonable offense in this country of wearing spectacles, though most people called him “Mr. Roosevelt.”

When he brought in cattle they looked with furtive glances at the “stuck up tenderfoot shassayin’ ’round, drivin’ in cattle and chasin’ out game.”

Even the unprejudiced waited askance till he made good. This he soon did. At intervals he would go out hunting for a day and sometimes make long trips.

The hunger, cold, and wet inevitably encountered were lost on him. Though no crack sharpshooter or broncho-buster he was a good shot, a good rider, and took his medicine like a man. “Fer a critter with a squint he war plum handy with a gun,” remarked one pioneer.

On the round-up he neither asked nor received any favors. He worked hard like any other cowboy, whether it was in the sweltering heat of midsummer, or in a blinding blizzard in early winter.

He helped break his ranch horses, and rode both good and bad.

Once, while on a round-up he was thrown from the saddle and broke the point of his shoulder; at another he cracked a rib. Being 100 miles from a doctor, these injuries had to heal themselves, and, besides, he had to get thru his work as best he could.

Dantz tells us that the hard work on the round-up told on Roosevelt till be became rather gaunt, yet with grim, bull-dogged energy, he went thru it. On all occasions he fraternized with the cow-boys; he rode, ate, and slept with them; and at night listened to their simply told stories before a campfire.

…

=====

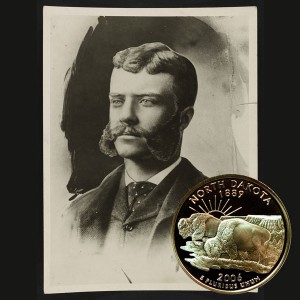

The North Dakota State Quarter Coin shows against a portrait of young Teddy Roosevelt from 1882.