Today, the Washington State Quarter Coin remembers when Captain George Vancouver saw the mountain and named it Mount Rainier 225 years ago.

In The National Magazine of June 1919, an article by C. T. Conover discussed the naming of the mountain and the many subsequent arguments to change the name.

=====

In a recent issue of the NATIONAL MAGAZINE appeared a beautiful view of Mount Tacoma from Tacoma, Washington, and two inspired poems on the subject.

Thirty-odd years ago the writer lived in Tacoma, and had Tacomacitis in its usual aggravated form. He has been thru all the phases of the malady.

He was told that the Indian name of the mountain was Tacoma, as the Tacoma people of today have been told, and that Rainer was a rank usurper. He believed it.

Finally he stumbled upon the fact that Tacoma was not actually an Indian word, and he then began a general research of the subject.

Now, when he goes to Tacoma, he goes around the back streets and registers under an assumed name.

Having implicit confidence in Joe Chapple’s honesty of purpose, and believing that he does not intend to set himself up as an authority on geographic names in opposition to the United States Geographic Board, he (the writer) will briefly state the main facts in this almost farcical comedy.

Captain George Vancouver, who first explored the Puget Sound region, and by right of discovery affixed geographical names, none of which have ever been questioned save only the name of Mount Rainier, in his “Voyage of Discovery to the North Pacific Ocean and Round the World,” London, 1801, under date of May 8, 1792, says:

“The weather was serene and pleasant and the country continued to exhibit between us and the eastern snowy range the same luxurious appearance. At its northern extremity Mount Baker bore by compass N. 22, the round, snowy mountain now forming its southern extremity, and which, after my friend Rear Admiral Rainier, I distinguished by the name Mount Rainier, bore N. (S.) 44E.”

In the words of the late veteran geographer, George David son, author of the “Pacific Coast Pilot,” and formerly of the United States Coast Survey:

“The accepted right of the discoverer in a new country, with uncivilized inhabitants, or with no inhabitants to apply geographic names, has never been traversed by competent authority.”

By this unquestioned right was Rainier christened by the first white man who ever beheld its majestic beauty and grandeur.

There is no record that it was known by any other name, by Indian or white man, until 1853, when Theodore Winthrop made a flying trip thru the Northwest and laid the foundation for the future controversy in these words in his work, “The Canoe and the Saddle”:

“Of all the peaks from California to Frazer’s River, this one before me was royallest. Mount Regnier Christians have dubbed it in stupid nomenclature, perpetuating the name of somebody or nobody. More melodiously the Siwashes call it Tacoma, a generic term also applied to all snow peaks.”

Mr. Winthrop was a bird of passage, entirely unacquainted with the Indian language, and so ignorant of the subject under discussion that he misspelled the word “Rainier.”

Still, this was the germ from which all the trouble arose, and Winthrop is referred to by every advocate of the name Tacoma, and Winthrop’s statement is always quoted, usually omitting the last nine words.

By elision of words even the Bible can be made to mean anything one wishes it to.

Winthrop, upon whose authority the controversy rests, definitely states, however, that the word “Tacoma” is a generic term applied to all Snow peaks.

It is rather a flimsy foundation, surely, for a geographical name.

Winthrop’s book did not reach Puget Sound for several years, and it naturally led to discussion among the early settlers, who had never heard the word before.

Many of the most intelligent pioneers believe that the sputtering, guttural use of the word “Tacobed” or “Dacobed” by the Indians after the appearance of Winthrop’s book was the usual Indian attempt to adopt a white man’s word.

Thus Ezra Meeker, still living, and a pioneer of 1853, a firm friend of the Indians, and in his day the largest employer of Indian labor on Puget Sound, a settler in the environs of Tacoma a generation before Tacoma was settled, in his book, ”The Tragedy of Leschi,” written in defense of an Indian chief, says:

“We have a like curious phenomenon in the case of Winthrop first writing the word ‘Tacoma’ in September, 1853. None of the old Settlers had heard that name, either thru the Indians or otherwise, until after the publication of Winthrop’s book, when it became common knowledge and was applied to a hotel in Olympia in 1866. However, as Winthrop claimed to have obtained the word from the Indians, the fact was accepted by the reading public, and the Indians soon took their cue from their white neighbors.”

Supporting Mr. Meeker’s theory is this testimony from Dr. Charles M. Buchanan, superintendent of the Tulalip Indian agency, and pre-eminently the greatest living authority on Indian languages and customs in the Northwest: “I have never considered ‘Ta-ko-bid’ a genuine Indian word. Several very intelligent Indians, Some of the most intelligent and reliable I have ever known, agree with me in the belief that it is merely an Indian attempt to say a word they have heard the whites use, and this appears to confirm Meeker.”

The late Thomas W. Prosch, historian, founder of the first newspaper in Tacoma, and Son-in-law of General McCarver, founder of the town of Tacoma, in the Washington State Historical Society publication, states that he has never been able to find the word “Tacoma” in any of the records of the state, territory, or nation, that Vancouver, Lewis and Clarke, Wilkes, White, or Fremont never appear to have heard of it, nor did the early missionaries, Hudson’s Bay men, or early settlers, and adds: “No one as far as I can learn ever wrote the word, put it in type or otherwise, before Winthrop. He wrote his book with the aid of a Chinook jargon dictionary.”

In 1868 General McCarver platted the present town site of Tacoma as “Commencement City,” but after reading Winthrop’s book he changed the name to Tacoma.

From the birth of Tacoma, in 1868, until March, 1883, Rainier was in universal use as the name of the mountain everywhere on Puget Sound and even in Tacoma.

The writer has a file of Tacoma newspapers confirming this fact.

On January 1, 1880, the Tacoma North Pacific Coast said editorially: “In this issue we publish a poem by Mrs. Belle W. Cook entitled ‘Mount Tacoma.’ We do not suppose, however, that names as well established as are Puget Sound, Mount Rainier, or Straits of San Juan de Fuca can be changed by an editor’s whim or an author’s sentiment. So we shall continue to apply the name of the old English rear admiral to our mountain, and call it Mount Rainier.’’

In the meantime the Northern Pacific Railroad Company acquired the town site of Tacoma as its Pacific terminus, and in March, 1882, the company’s official organ, the Northwest Magazine, contained the announcement that the company’s literature and agents would hereafter use the name “Mount Tacoma” for the mountain “instead of Rainier, which the English captain Vancouver gave to this magnificent peak when he explored the waters of Puget Sound in the last century.”

This changed the whole aspect of the situation. Winthrop’s statement had heretofore had no general effect in changing the name of the mountain, but when the only trunk line railroad reaching the Pacific Northwest adopted the word ‘’Tacoma” in all its extensive advertising literature, there was a full-fledged controversy at once.

However, even after the Northern Pacific’s edict, the Tacoma newspapers had great difficulty in accustoming themselves to the new name, and for a year or so most frequently used the name “Rainier.”

As late as July 12, 1884, the Tacoma Daily News referred to “Mount Tacoma, which, by the way, is Mount Rainier everywhere except in Tacoma.”

Soon, however, Tacoma took up the fight to change the name manfully and womanfully, and has continued it to this day.

It is rather a nice thing to have the most majestic scenic feature in the nation named after one’s home town.

A collection of wonderful Indian legends came into existence featuring dusky maidens, romantic lovers and weird fantasies of all sorts.

George Francis Train, the eccentric publicist, was enlisted in the cause and wrote grotesque copy for the Tacoma papers, alternate lines written in red and blue pencil.

Finally, about 1889, he was sent around the world with a private secretary in a globe-encircling tour against time, chanting the touching refrain:

“Tacoma! Tacoma!! Aroma! Aroma!! “Seattle! Seattle!! Death rattle! Death rattle!!”

Mr. Train was long since gathered to his fathers, but his secretary of that day is continuing “the fight for justice to the mountain.”

Finally, in 1890, the contest reached the ears of the United States Board on Geographic Names, and a hearing was ordered, and all available testimony submitted.

The board unanimously decided for Rainier.

Again, in 1917, after twenty-seven years of effort, Tacoma again got the matter before the United States Geographic Board and again the decision was for Rainier, the board stating in its decision that “No geographic feature in any part of the world can claim a name more firmly fixed by right of discovery, by priority and by universal usage for more than a century. So far as known, no attempt has ever been made by any people in any part of the world to change a name so firmly established.”

Dr. C. Hart Merriam, a distinguished member of the board, in a conclusive paper on the subject at that time, published by the government printing office, gives expression to a pertinent fact, thus:

“If the people of Tacoma are so eager to call places by their Indian names, why have they not adopted the unquestioned aboriginal name ‘Shuh-bah-lup instead of Tacoma for their own city?”

While Tacoma does not appear to be a genuine Indian word, and while, according to State Senator William Bishop, himself the son of a full-blooded Indian and possessing high intelligence and much knowledge of Indian lore, no Indian can pronounce the word, there are authentic Indian names for Rainier.

Dr. William Frasier Tolmie, chief factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company and a learned man, in his diary in 1833, fifty years before the controversy, and twenty years before the white man’s entrance into the Puget Sound country, records the Indian name as “Puskehouse.”

Peter Stamup, a full-blooded Indian born in sight of Rainier, a member of the bar and a Presbyterian minister for years, probably the most intelligent Indian ever born on Puget Sound, gives the Indian name as “Tiswauk.”

This name and a variation, “Stiguak,” is confirmed by F. H. Whitworth, son of the early president of the University of Washington, and he himself interpreter in pioneer times for the superintendency of Indian affairs for Washington, adding that in all his contact with the Indians in his capacity as interpreter he never heard the name “Tacoma” applied to the mountain by any Indian, nor, in fact, by any white man, until after the publication of Winthrop’s book.

The venerable Father Boulet, who spent the greater part of his life as a missionary among the Indians, and who recently was still living, gives the Indian name of Rainier as “Tu-ah-ku.”

Some early historians, however, follow Winthrop in the claim that Tacobet and its variants was a generic term applied to all snow peaks.

The late Elwood Evans, an eminent Tacoma lawyer and historian, in his “History of Oregon and Washington,” says:

“It was known as Rainier to all early settlers up to the time of the completion of the Northern Pacific Railroad to Tacoma. The railroad then re-named the mountain after the city, claiming that to be its original name. The truth is, however, that the Puyallup Indians called all snowy peaks Tak-ho-ma.”

The late General Hazard Stevens, who was the son of the first governor of Washington, and who made the first ascent of Rainier, in an interesting article describing his ascent in the Atlantic Monthly for November, 1876, states that “Tak-homa, or Ta-homa, is an Indian generic term for mountain, just as we use the word “mount’ as Takhoma Wynatchie, or Mount Wynatchie.”

Clinton A. Snowden, a well-known Tacoma journalist, in his notable work, “Rise and Progress of an American State,” Volume 4, says of the early efforts to change the name:

“The newspapers and people of Oregon joined this opposition. The attempt to change the ancient name of the majestic mountain was declared to be nothing less than a sacrilege. It was simply a scheme of a lot of real estate boomers and speculators to turn a great world landmark into an advertisement, to reduce sublimity itself to the level of a signboard. . . . The newspapers of Tacoma and the people of the town stood sturdily for the change and made such a fight as they were able. The Indians were appealed to for evidence on both sides, and after their custom generally furnished something that was satisfactory to both. Edward Huggins, last of the Hudson’s Bay factors, who had lived for thirty years among the Indians, had never heard them use any name other than La Monte, the Chinook name. Mrs. Huggins, who was a daughter of John Work, and who was born on the Coast, says, however, that “the name was Tachkoma, and that everything in the shape of a mountain or large mound covered with snow was called Tach koma or Tacobah.”

Julian Hawthorne’s “History of Washington, the Evergreen State,” says that Vancouver named the mountain Rainier, “which was accepted by the early settlers up to the time of the completion of the Northern Pacific Railroad; then re-naming the mountain after the city, the company called it Mount Tacoma.”

Dr. George Otis Smith, director of the United States geological survey, in a letter dated February 28, 1908, and published in the proceedings of the Washington State Historical Society, finally by incontrovertible evidence, confirms the fact that Tacoma was certainly not the Indian name for Rainier.

He states that in 1901, when in charge of the investigation of the northwestern boundary of the United States, he made use of an old boundary map which had not been published, but which he had photographed from the state department archives; that this old map antedates most of the settlement of the state of Washington, and gave both the Indian and the English names, when there were English names, since the country was then comparatively unknown to white men.

Dr. Smith says: “Now, the interesting fact is that Mount Baker was given not only this English name, but the Indian name as well—Tahoma. In other words, the Indians applied this name, which you know signifies The Great Mountain, not only to Rainier, but also to Mount Baker.

The fact is the Siwash would speak of the largest mountain in his vicinity as ‘the mountain’ or ‘Tahoma,’ just as the Tacoma man will today refer to ‘the mountain,’ meaning Rainier, or the ranchman in the vicinity of Nooksack will designate Mount Baker as ‘the mountain.’”

Not one man in fifty in the state of Washington calls the mountain Tacoma. The name is practically unheard of outside of the city of Tacoma, and even in the county in which Tacoma is situated there are many strong opponents to the efforts to change the name.

Bibliography of Washington Geology and Geography, officially issued by the state in 1913, cites forty-seven Publications on the mountain.

In forty-six cases the mountain is called Rainier; in one case, Tacoma.

Long years ago the Northern Pacific abandoned the name “Mount Tacoma,” and Charles S. Fee, then general passenger agent, said to a delegation of protesting Tacoma citizens:

“Gentlemen, we have carried this farce as far as we going to for advertising purposes. The name has officially been declared to be Rainier, and that is what we shall call it. You may call it what you please.”

=====

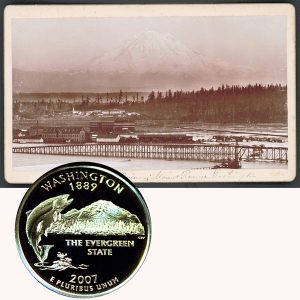

The Washington State Quarter Coin shows with an image of Tacoma with Mount Rainier in the background, circa late 1800s.