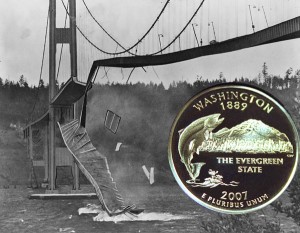

Today the Washington State Quarter Coin helps us remember the morning of November 7, 1940 when the winds of Puget Sound broke Galloping Gertie.

Newspapers of the day provided an eyewitness account written by Professor F. B. Farquarson, who was on the bridge studying the sway and how to correct the problem.

=====

I was the only person on the Narrows bridge when it collapsed. It wasn’t bravery on my part. I didn’t believe it would happen, and besides, I was anxious to get a motion picture of the unusual way the bridge was acting for my official records.

When I arrived about 9:45 am, the bridge was moving in a normal way, in the familiar rippling motion we were studying and seeking to correct.

About half an hour later it started a lateral twisting motion in addition to its vertical waves. It had never done that before. There was considerable noise of stress and strain. As the motion increased in severity, lamp posts were jerked back and forth in a side motion and at least six snapped off while I was on the bridge.

As I was taking my pictures, I noticed one auto stalled in the middle of the span, but was too busy to pay it much attention. Previously I had seen two men near the car. They were deathly sick. They stumbled and crawled to the Tacoma end.

I looked in the car and saw a dog in there. Then I went ashore to get some more films for my camera and walked out on the careening span again.

About 10 minutes later, as the pitching, twisting and rolling increased, the dog occurred to me again. Since I love dogs, I staggered out to mid-span again and opened the door and tried to coax him out. The animal was sick and terrified. As I tried to calm him he bit me on a knuckle.

Then I gave up the attempt, deciding that even if I succeeded in getting the dog out he’d probably fall overboard. So he stayed and plunged to his death a few minutes later in his master’s car.

A few minutes later I saw a side girder bulge out on the Gig Harbor side, owing to a failure, but though the bridge was buckling up as an angle of 45 degrees, the concrete didn’t break up. Even then I thought the bridge would be able to fight it out.

Looking toward the Gig Harbor end, I saw the suspenders —the vertical steel cables—snap off and a whole section of the bridge cave in.

The main cable over that part of the bridge, freed of its weight, tightened like a bow string, flinging the suspenders into the air like so many fish lines.

I realized the rest of the main span of the bridge was going, so I started for the Tacoma end. Behind me the rest of the bridge plunged into the Sound.

By that time I was between the tower on the Tacoma side and the Tacoma shore. I thought I was out of danger, but suddenly the bridge dropped from under me. I fell and broke one of my cameras. I got up and started, only to have the bridge fall out from under me again.

The part of the bridge I was on had dropped fully 30 feet, owing to the sudden shift of weight on the main cable.

It was one of those things that couldn’t happen once in a thousand years, a combination of conditions that no one anticipated.

=====

Now, engineers talk about “resonant load” and how Napoleon told his soldiers to break step over bridges — especially suspension bridges—to avoid the “dance of death.”

The winds on Puget Sound that fateful day blew at the right frequency to add too much “resonant load” to the five-month old Tacoma Narrows bridge.

The Washington State Quarter Coin shows against the falling Tacoma Narrows Bridge.