Today, the Florida State Quarter Coin remembers the Adams – de Onis treaty and the transfer of the area from Spain to the United States on February 22, 1819 and again two years later on the same date.

Not only did the negotiations take a long time, but the actual transfer did not move smoothly either.

From A History of the United States by Edward Channing, published in 1922:

=====

The propositions that underlay the negotiations of 1818 were that the Spaniards should give up all claims to territory on the North American continent east of the Mississippi River and also to the territory on the Northwest Coast north of California.

In exchange the United States would give up all claims to Texas or to the country between the Rio Grande and one of the Texan Rivers, — the Colorado, the Sabine, or some other — and in addition pay five million dollars to its own citizens to extinguish claims that they were supposed to have against the Spanish government for spoliations committed on American commerce during the French wars.

Jefferson had some objections to any bargain that would restrict the western extent of the United States.

Monroe answered him that the boundary in that wilderness could be easily arranged with whatever new government might be formed in Mexico, — which seemed to be on the point of seceding from Spain.

He maintained, moreover, that the immediate settlement of our western boundary was necessary for the internal peace of the country.

The negotiations dragged on and on, until Adams was thoroughly tired.

His general proposition was to take Florida and give up all territory west of the Texan Colorado and south of the forty-first parallel; De Onis, on his part, proposed the Sabine River and the forty-third parallel.

Finally, somewhat against his will, but in conformity with the wish of the President, Adams compromised on the Sabine and the forty-second parallel.

The treaty was signed on February 22, 1819, the American ratifications were handed over and the documents were sent to Spain

Adams had scarcely written a joyful sentence or two in his diary over the completion of the Florida negotiations when doubt arose as to the completeness of the settlement.

The treaty had provided that all grants of land made by the Spanish authorities before January 24, 1818, should be regarded as valid; it now appeared that some very large grants which the negotiators had in mind in selecting this date were, as a matter of fact, actually dated January 23, and therefore had been validated by the provision of this treaty which had purposely been drawn to exclude them.

Adams at once addressed De Onis. The Spaniard appeared to be shocked and signed a statement that the validity of these land grants was not recognized in the treaty.

Before many months passed away, further mortification appeared in the shape of the refusal of the Spanish government to ratify the treaty at all.

Possibly, someone in authority at Madrid wished to barter ratification for a recognition of these land grants; but it is more likely that the Spanish government hoped that by withholding ratification it could postpone the recognition of the Spanish American republics, perhaps indefinitely.

The six months provided for the exchange of ratifications passed away and then came a revolution in Spain that made the king a constitutional monarch and deprived him of the power to alienate Spanish territory.

As the probability of the ratification of the treaty faded away, its value became more manifest to American eyes.

Monroe and Jefferson and Adams were one in condemning the actions of the Spaniards.

It was even suggested that the United States might be justified in taking possession of Florida without any ratification; but before anything was done, the Spanish Cortes and the king decided to ratify and the transaction was completed at Washington on February 22, 1821, two years to a day after the actual signing of the instrument by Adams and De Onis.

The ratification of the treaty did not put an end to the friction between American officials and the Spaniards.

The treaty obliged the latter to hand over the province within six months after the exchange of ratifications and to deliver up the forts and the archives.

The archives had been removed to Havana, for Florida had been under the administration of the governor general of Cuba.

An American officer was sent to Havana, but after many delays he came away without the papers.

Then, too, questions arose as to whether forts included artillery and whether the obligation of the United States to transport Spanish officials and employees and their families from Florida to Cuba included feeding them on the voyage.

Adams declared that a fort included artillery and the Spaniards insisted that transportation included provisions.

Monroe sent Andrew Jackson to take possession of the ceded province and govern it, until other arrangements should be made.

Congress had already provided that for a limited time the officers appointed by the President to take possession of Florida should have all the powers that the Spanish authorities had exercised; and, as they had exercised practically all powers, Jackson’s authority was unlimited by law or usage.

Jackson proceeded to Pensacola, ” took possession,” issued decrees and orders, and then, in the somewhat naive language of his biographers, was waited upon by a daughter of a deceased Spanish official.

She declared that the Spaniards, who had not yet gone, were taking with them papers that were necessary to prove her title to land and property in Florida.

Jackson at once sent an officer to demand the papers and upon these being refused, he directed them to be seized and also that Colonel Callava, the recalcitrant official, should be brought before him.

This was done and, after some debate, Jackson sent him to prison (1821). It was at this point that Eligius Fromentin, whom Monroe had appointed judge in Florida, ordered Callava to be produced bodily in his court, which led to Fromentin’s being summoned into Jackson’s presence.

From this point, the matter diffused into letter writing and Jackson soon after resigned his appointment and retired to his Tennessee plantation.

…

=====

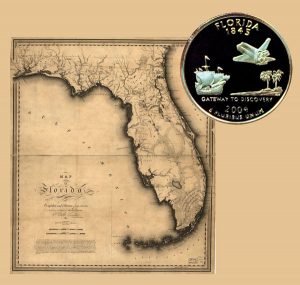

The Florida State Quarter Coin shows with an image of territorial map, circa 1823.