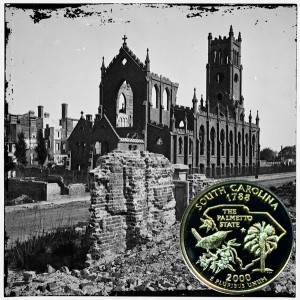

Today, the South Carolina State Quarter tells the story of Charleston 153 years ago.

The evening was cold with a strong wind blowing from the northeast.

At about half past eight in the evening of December 11, 1861, a fire began in the W.P. Russell & Co. manufacturing building. The large factory produced sashes and blinds.

The fire grew among the flammable materials, and the strong winds quickly spread the flames to the nearby buildings.

Soon, the fire became so extensive that efforts to control it were in vain.

The flames consumed businesses and livelihoods in a broad line extending from the foot of Hasell street, on the Cooper River, to the end of Tradd street, on the Ashley River.

The burned area covered 540 acres with loss estimates into the millions of 1861 dollars.

One small 1861 news article in the Painesville Telegraph claimed:

The Charleston Fire. The aggregate loss of property in buildings, goods, etc., is almost incredible. The Charleston Courier of the 16th roughly estimates at full ten millions of dollars, on which the insurance was comparatively limited. Most of the policies were in Charleston, Augusta, Savannah and other Southern Companies, many of which will be unable to pay one fourth of the loss incurred.

Published in the Charleston Mercury on January 1, 1862:

A Proclamation

The calamitous fire which has spread through our city, upon all who have been within its reach, inflicts loss and suffering. But there are many who, in its ravages, have lost so much, that the aid of all who have been fortunate in escaping its effects, should be, and will be, generously offered for their relief. To secure the most useful application of whatever may be thus contributed for the relief of those who are suffering, the following committee has been appointed. It will forthwith organize itself, make immediate application to our fellow-citizens for such aid as they can afford, and promptly relieve, as far as possible, with shelter, food and clothing, those whose misfortunes have deprived them of these necessaries.

Charles MacBeth

December 19th, 1861

Mayor of Charleston

The proclamation listed the committee members and noted where and to whom to contribute money, provisions and clothing.

Over the next four years of wartime, the people of Charleston did not rebuild the burned area.

In the latter years of the war, the remaining city was shelled and burned again during fighting between the north and south.

In April 1865 after the war ended, the Oceanus Steamer carried people from New York to visit Fort Sumter and Charleston for the raising of the Union flag.

One observer noted,

“Advancing along these streets, we come to the district burned in 1861. That fire consumed nearly a fifth part of the city. These ruins, which no attempt has been made to rebuild, stand in all their desolateness, increased by the havoc of the bombardment. The tall chimneys, grim and charred, the dilapidated walls, overgrown with moss, the cellars, rank with grass, weeds and thistles, the streets without pavement, and ankle-deep with sand, are a startling commentary upon the accounts with which we were favored during the war.”

It took time, many years, but Charleston rose from the ashes to become a thriving city once more.

The South Carolina State Quarter shows against the destruction of the December 11, 1861 fire, in particular, the Roman Catholic Cathedral of St. John and St. Finbar (Broad and Legare Streets).