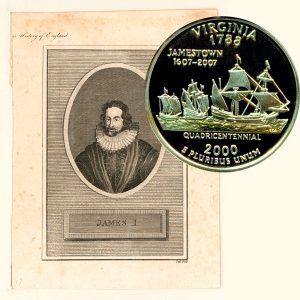

Today, the Virginia State Quarter Coin remembers when the King of England, James I, authorized the charter for settlement in America.

From the Handbook of the United States Political History for Readers and Students, compiled by Malcolm Townsend, published in 1905:

=====

Development of a Commonwealth.

The first permanent settlement made in America under the auspices of England was under the following charter: —

April 10, 1606. King James I. of England issued to an association of nobles, gentlemen, and merchants residing at London, called the “London Company,” a patent authorizing them to possess and colonize the land lying between the 34 and 41st degrees of north latitude.

“The intervening coast between latitude 38° and 41°, or between the present Rappahannock and the Hudson rivers, was to be common to both the ‘London Company’ and the ‘Plymouth Company,’ but neither was to plant a settlement within 100 miles of a previous settlement of the other.”

April 10, 1606. The King issued a second instrument to a similar body, organized at Plymouth, in southwest England, called the “Plymouth Company,” covering the territory between the parallels 38th and 45th degree of north latitude.

=====

From The Civil Government of the States, and the Constitutional History of the United States, by P. Cudmore, Esq., published in 1875:

=====

Colonial History.

The first settlement of Englishmen in North America was attempted in the reign of Queen Elizabeth. Her first patent was issued to Sir Humphrey Gilbert in 1578. An abortive attempt to settle a colony in Virginia was made by Sir Walter Raleigh, in this reign, under a transfer of Gilbert’s patent.

In the year 1603, one hundred and ten years after the discovery of the New World, there was not an Englishman in America.

In 1606, the Spaniards had established posts in Florida, and the French had settlements in New France, afterwards named Canada.

James I of England, who succeeded Elizabeth, by an ordinance, April 10, 1606, divided all of North America lying between 34 and 45 degrees of latitude into two districts.

The first district was called Southern Virginia; and the second, Northern Virginia (Plymouth Colony) which was changed to New England.

Southern Virginia was granted to the London company in 1607, by James I, and Northern Virginia, (Plymouth Colony) or New England was granted to the Plymouth company November 3, 1620, composed “of forty noblemen, knights and gentlemen, called the council,” established at Plymouth, in the county of Devon, for the planting, ruling, and governing New England in America, with the Earl of Warwick as head of the corporation.

South Virginia extended from the parallel of 34 to 40 degrees, and from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

The first settlement, under the Grant to the London company, was made at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607.

The management of the colony was given to Christopher Newport and Captain John Smith.

“The general superintendence of the colonies was vested in a Council, resident in England, named by the king, and subject to all orders and decrees under the sign manual; and the local jurisdiction was entrusted to a Council also named by the king, and subject to his instructions which was to reside in the colonies. Under these auspices, commenced, in 1607, the first permanent settlement in Virginia.”

In 1607, a new charter was granted to the company. The colony was to be governed by a governor and council. This was a close corporation.

The aristocracy of England, at this period of English history, had little respect for the people. Indeed the idea of a government of the people was repugnant to the aristocracy or wealthy classes of England.

The governor was appointed by the Company.

The people of England had no idea of a Town Meeting as a body politic or a town meeting — “where the people met in their aggregate capacity to elect local officers.”

For in England, the country was divided into counties, which were represented by Knights elected, generally, by the land owners. There were also certain boroughs represented by burgesses, generally, representing the mercantile interests.

The idea of the people meeting in their collective capacity, as in the Republics of Greece, was unknown in England.

In 1619, the people of Virginia were able to obtain a voice in the government of the colony.

Virginia colony was divided into eleven boroughs; and two members from each borough formed the House of Burgesses, in imitation of the British House of Commons.

This assembly was the first house of representatives in America.

As the people were poor and lived in log-cabins they did not think of forming a House of Lords.

It might be here remarked that the Southern Colonies followed the institutions and laws of old England which suited their wants and condition. That the people of all the colonies borrowed their laws from the English model, except the Puritans of New England, who followed the laws of Moses — the Bible was the basis of their laws and government.

And as the colonists of Virginia were of the Church of England, they established parishes and maintained the clergy with tithes as in England.

The crown of England became jealous of the extensive powers and territory of the London company. And at last King James I dissolved this great monopoly — this overgrown corporation.

The executive powers were in this corporation.

King Charles I recognized the authority of the Assembly of Virginia. And as the struggle in England was between Charles and the Parliament — the latter being Puritans, and the former of the Church of England, Virginia took part with the king.

The authorities banished all who would not use the liturgy of the Church of England.

So Virginians, as well as the Puritans were intolerant — both established church and state.

In 1758, the legislature of Virginia passed an act that the people might commute for the tobacco, in money, a tribute which had to be paid to the ministers of the Church of England.

For in the early days of the colony tobacco was the usual currency; for nearly all payments were made in tobacco, as afterwards in the Western States, men had to take what was then called “store pay,” that is, an order on a store for goods.

Virginia, in a great measure, retained the old English aristocratic customs and prejudices of caste.

The land holders, as in the old country, in that age, were the aristocracy.

They were called the upper class, and the landless the lower class. The upper class was principally attached to the crown.

The people of the South and of New England were dissimilar in politics, religion, manners and customs — they were not of the same race.

The Virginians were the descendants of the Normans — “Cavaliers;” and the Puritans of the Saxons, or “Roundheads.”

The colony of Virginia restricted the right of suffrage to householders; and made the English church the state church. And it compelled attendance at the worship of this church under penalty of twenty pounds.

Penal laws were passed against Quakers and Baptists.

The colonial legislature and Governor Berkeley were the embodiment of despotism.

Berkeley is reported to have said, “I thank God that there are no free schools or printing, and I hope that we shall not have them these hundred years!”

This was the status of the colonial legislature of Virginia until Bacon’s rebellion, in 1676, when the old intolerant legislature was dissolved and a more liberal one elected. The governors of the colony were appointed by the king.

=====

The Virginia State Quarter Coin shows with an artist’s image of James I.