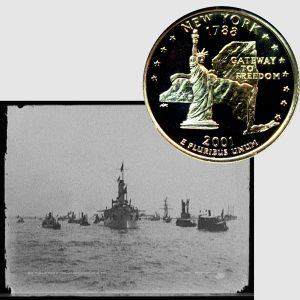

Today, the New York State Quarter Coin remembers the naval parade in New York Harbor of the successful Santiago fleet on August 20, 1898.

From the Scientific American of September 3, 1898:

=====

Saturday, August 20, was a red-letter day in the history of New York city, for when the seven armored warships of Admiral Sampson’s fleet, fresh from the smoke of battle and bearing the scars of a victorious struggle, steamed in stately line up the North River, New Yorkers gazed upon a sight the like of which no city has ever witnessed before.

True, there have been other naval parades signalizing the close of successful wars. Victors in even greater numbers had dressed ship, and bells had swung and trumpets blared at triumphal naval parades long before the Dutch founders of New York set foot upon Manhattan Island.

But never before has such a fleet of armored battleships and cruisers, representing the latest ideas of warship construction, come home to parade in triumph with the scars of a victorious struggle fresh upon it.

Immediately after the signing of the Peace Protocol orders were given for the battleships and cruisers of Sampson’s squadron to come north to be docked and overhauled at the Brooklyn navy yard.

In agreement with a popular wish, while the ships were coming up the coast, instructions were given for the fleet to parade from Tompkinsville, on its arrival at New York, up the North River to Grant‘s tomb and return.

The instructions to this effect were delivered to the incoming fleet as it was working its way up the Jersey coast in the gray dawn of the morning. The photograph showing the flagship “New York” with the other vessels astern was taken while approaching the “New York” at 5 A. M. by our artist on the government boat “Nina.”

The dispatches were handed aboard, and by the time the fleet reached Staten Island, the ships were in trim for the parade, and the crews, dressed in their picturesque white duck, were formed up on the upper decks and superstructures in the picturesque grouping shown in the illustrations.

The flagship “New York,” with Admiral Sampson on board, led the way. The sight of this handsome vessel, whose outline is perhaps the most familiar to the public of all the ships of the navy, recalled the many incidents of the War in which she has figured:

The blockade of Havana, the bombardment of Matanzas, the cruise to Porto Rico, ending in the attack on San Juan, in which she was struck by a shell and one of her seamen killed, and finally her long stern chase at Santiago, where the chances of war had decreed that she should only be “ in at the death,” missing the great fight that preceded it.

A few hundred yards astern loomed up the “Iowa,” bigger than the “New York” (8,200 tons) by 3,140 tons, and looking especially formidable with her lofty spar deck and its forward 12-inch guns, carried 26 feet above the water line.

The “Iowa ” bore the marks of the San Juan and Santiago engagements.

Forward on the starboard bow two square patches of plate showed where a couple of big shells had entered when the “Iowa” was exposed to the first rush of Cervera‘s fleet at Santiago. A score of holes on the berth deck show where the flying fragments of one of the shells tore through the tough steel plating.

On the spar deck, holes big and little testify to the slaughter which another bursting shell would have caused among the 6-pounder batteries had the men not been sent below decks during the San Juan bombardment.

Next came the “Indiana,” one of the famous trio of which the “Oregon” is just now the most popular member.

She lay to the eastward of the harbor when the Spanish fleet came out, and it was only the unfortunate fact that her boilers were in trouble that prevented her from joining in the chase.

Although not the largest in displacement, the “Brooklyn,” with her lofty bow, towering smokestacks, and great length, was, perhaps, the most impressive vessel in the fleet.

The comparative inaction of this vessel in the earlier stages of the war was more than atoned for in the splendid opportunity which she was given in the Santiago fight.

When the Spanish fleet headed for the west, the “Brooklyn” was the only vessel that lay directly in their path. They were all headed directly for her (the captured Spaniards say with the intention of crippling her by their concentrated fire, and so escaping from the slower battle ships).

As the “Vizcaya” drew near, the “Brooklyn” swung out in a wide turn to sea and then took up the chase in company with the “Oregon.”

She carried more of the scars of conflict than any other vessel in the fleet, having been struck some thirty-six times.

Most of the hits were received in the long range duel which she fought with the “Christobal Colon” during the latter’s 48-mile dash for liberty.

Astern of the “Brooklyn” came the “Massachusetts,” looking uncommonly weatherstained, and therefore very much like a warrior just in from hard service.

The “Massachusetts,” like the “New York,” had the misfortune to be absent from her station when the battle of Santiago took place. She was coaling several miles down the coast at the eventful hour for which during many a long day and night, her ship’s company had impatiently waited.

The chances of war were largely answerable for the fact that the “Massachusetts” was not so much in the public mind as some other ships that steamed by the applauding thousands that thronged every vantage point on each side of the river.

The great similarity between the “Indiana,” “Massachusetts,” and the “Oregon,” and the impossibility of the average spectator identifying the Pacific coast vessel, was all that prevented the “Oregon” from receiving a special ovation from the multitude.

She followed the “Massachusetts,” and her freshly painted hull, with a brilliant coat-of-arms conspicuous at her bow, had covered up all suggestions of that 14,000 mile journey round “the Horn”and the death-dealing blows this splendid ship had dealt at Santiago.

Remarkable to relate, the “Oregon” has less marks to show for the war than any other ship. She is practically unscathed, and proves again the old truth that the best protection to a ship is a crushing fire delivered by her own guns.

The excellent performance of the “Oregon” was due to rigid discipline, careful and continual inspection, and the fact that everything in the ship was at all times tuned up to concert pitch.

We have just learned from one of her officers an interesting fact regarding the speed shown by the “Oregon” at Santiago.

It seems that some of the blockading vessels were repairing their boilers, one at a time, keeping the fires banked in the other three. At the earnest request of the chief engineer of the “Oregon,” fires were kept going under all four of her boilers, the chief having declared that they were in sufficiently good repair to stand a few hours pressing under forced draught.

A day or two later the Spanish fleet made its attempt, and the “Oregon” was able to pass through our fleet with all boilers going and the forced draught in full swing.

During the last half hour of the chase she was running well up to her trial speed.

Last in the procession was the second-class battle ship “Texas.” Not much over half the size of the “Iowa,” and representing an earlier day in battleship design, she has won laurels in the war second to none.

This vessel does not appear in our illustrations, as we have recently shown and described her at considerable length in our issue of August 20.

The vessels will all be docked in the new dry dock, known as No. 3, at the Brooklyn navy yard, which is about to be opened after the long months of work that were necessary to repair the leaks which appeared shortly after it was turned over by the contractors.

=====

The New York State Quarter Coin shows with an image of the return of Santiago fleet, New York Harbor, Aug. 20, 1898.