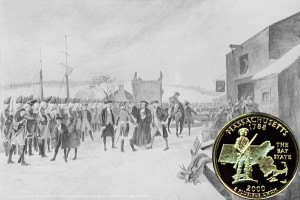

Today, the Massachusetts State Quarter Coin tells the story of one man’s remembrance of that fateful day 240 years ago, that almost became the first battle of the revolution.

Charles M. Endicott authored the Account of Leslie’s Retreat at the North Bridge in Salem, on Sunday, February 26, 1775, published in 1856.

He included Mr. William Gavett’s recollections:

=====

On Sunday, 26th February, 1775, my father came home from church rather sooner than usual which attracted my notice; and said to my mother “the reg’lars are come and are marching as fast as they can towards the Northfields bridge;” and looking towards her with a very solemn face remarked “I don’t know what will be the consequence but something very serious, and I wish you to keep the children in.”

I looked out of the window just at this time and saw the troops passing the house. My father then stepped out, and stood at the foot of the yard looking into the street. While there, our minister Mr. Barnard came along and took my father by the arm, and they walked down towards the bridge beside the troops.

My father was very intimate with Mr. Barnard, but was not a deacon of his church as some accounts state. This is all I saw of the affair myself; what I was afterwards told, the subject being very often discussed in my hearing for a long time, is as follows:

Col. David Mason had received tidings of the approach of the British troops and ran into the North Church, which was contiguous to his dwelling, during service in the afternoon, and cried out, at the top of his voice, “the reg’lars are coming after the guns and are now near Malloon’s Mills.”

One David Boyce, a Quaker, who lived near the church, was instantly out with his team to assist in carrying the guns out of the reach of the troops, and they were conveyed to the neighborhood of what was then called Buffum’s hill, to the N. W. of the road leading to Danvers and near the present estate of Gen Devereux.

My father looked in between the platoons, as I heard him tell my mother, to see if he could recognize any of the soldiers who had been stationed at Fort William on the Neck, many of whom were known to him, but he could discover no familiar faces—was blackguarded by the soldiers for his inquisitiveness, who asked him, with oaths, what he was looking after.

The northern leaf of the draw was hoisted when the troops approached the bridge, which prevented them from going any further. Their commander (Col. Leslie) then went upon West’s, now Brown’s, wharf, and Capt. John Felt followed him.

He then remarked to Capt. Felt, or in his hearing, that he should be obliged to fire upon the people on the northern side of the bridge if they did not lower the leaf.

Capt. Felt told him if the troops did fire, they would be all dead men or words to that effect. It was understood afterwards that if the troops fired upon the people, Capt. Felt intended to grapple with Col. Leslie and jump into the river, for said he “I would willingly be drowned myself to be the death of one Englishman.”

Mr. Wm. Northey, observing the menacing attitude assumed by Capt. Felt, now remarked to him, “don’t you know the danger you are in opposing armed troops, and an officer with a drawn sword in his hand?”

The people soon commenced scuttling two gondolas, which lay on the western side of the bridge, and the troops also got into them to prevent it.

One Joseph Whicher, the foreman in Col. Sprague’s distiller, was at work scuttling the Colonel’s gondola, and the soldiers ordered him to desist and threatened to stab him with their bayonets if he did not—whereupon he opened his breast and dared them to strike—they pricked his breast so as to draw blood.

He was very proud of this wound in after life and was fond of exhibiting it.

It was a very cold day, and the soldiers were without any overcoats and shivered excessively, and showed signs of being very cold.

Many of the inhabitants climbed upon the leaf of the draw and blackguarded the troops.

Among them was a man, (name not recollected,) who cried out as loud as possible, “Soldiers, red jackets, lobster coats, cowards, d—na—n to your government!”

The inhabitants rebuked him for it, and requested nothing should be done to irritate the troops.

Colonel Leslie now spoke to Mr. Barnard, probably observing by his canonical dress, that he was a clergyman, and said, “I will go over this bridge before I return to Boston, if I stay here till next autumn.”—

Mr. Barnard replied, he prayed to heaven there might be no collision; or words of a similar import.

Then the Colonel remarked, he should burst into the stores of William West, and Eben Bickford, and make barracks of them for his troops until he could obtain a passage; and turning to Captain Felt said, “By God! I will not be defeated;” to which Captain Felt replied, “You must acknowledge you have already been baffled.”

In the course of the debate between Colonel Leslie and the inhabitants, the Colonel remarked that he was upon the King‘s highway, and would not be prevented passing over the bridge.

Old Mr. James Barr, an Englishman, and a man of much nerve, then replied to him; “it is not the King’s highway, it is a road built by the owners of the lots on the other side, and no king, country or town has anything to do with it.”

The Colonel replied, “There may be two words to that;” and Mr. Barr rejoined, “Egad, I think that will be the best way for you to conclude the King has nothing to do with it.”

Then the Colonel asked Captain Felt if he had any authority to order the leaf of the draw to be lowered, and Captain Felt replied there was no authority in the case, but there might be some influence.

Colonel Leslie then promised, if they would allow him to pass over the bridge, he would march but fifty rods, and return immediately, without troubling or disturbing anything.

Captain Felt was at first unwilling to allow the troops to pass over on any terms, but at length consented, and requested to have the leaf lowered.

In this, he was joined by Mr. Barnard and Colonel Pickering, and the leaf was lowered down.

The troops then passed over, and marched the distance agreed upon without violating their pledge, then wheeled and marched back again, and continued their march though North street, in the direction of Marblehead.

A nurse, named Sarah Tarrant, in one of the houses near the termination of their route, in Northfields, placed herself at the open window, and called out to them:—”Go home and tell your master he has sent you on a fool’s errand, and broken the peace of our Sabbath; what,” said she, “do you think we were born in the woods, to be frightened by owls?”

One of the soldiers pointed his musket at her, and she exclaimed, “fire if you have the courage,—but I doubt it.”

The inhabitants generally, including the women, congregated on Odell’s Hill, where they could see all that was passing at the bridge, and waved their handkerchiefs, and cheered the inhabitants in token of encouragement, showing that but one spirit animated the whole mass.

A company of militia from Danvers, under Captain Samuel Eppes, came into town, and went back of Colonel Sprague’s distillery, and sat down, so as to expose their persons as little as possible, watching the movements at the bridge until all was over.

The account recently published of Colonel Pickering’s being on the North side of the bridge with forty armed militia, Mr. Gavett says “is all poetry,” it has no foundation whatever.

The Colonel was on the south side of the bridge like any other citizen. In Marblehead, a company of militia turned out to be ready for any emergency.

It was thought that one Colonel Sargent had the principal agency in conveying the information about the guns to General Gage.

=====

The Massachusetts State Quarter Coin shows against an artist’s rendition of the standoff at the North Bridge.