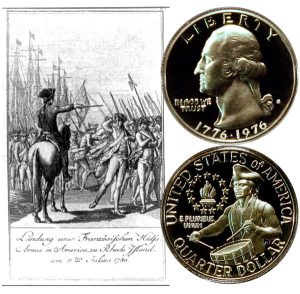

Today, the Washington Bicentennial Quarter Coin remembers the meeting between Washington and Rochambeau on May 22, 1781.

After almost a year of not working well together, some historians believe the plans discussed at the meeting 236 years ago led to the surrender at Yorktown and the end of the war.

From the New Outlook, Volume 24, edited by Alfred Emanuel Smith and Francis Walton, published in 1881:

=====

The French at Yorktown. By Eliot McCormick.

When Admiral de Terney set sail from Brest on the 6th of April, 1780, bringing Rochambeau and 6,000 troops to the help of America, neither he nor his companion, nor the King of France, who had sent them, could faintly imagine the far off consequences of the enterprise.

If his Most Christian Majesty had guessed that he was giving an impulse to Republican sentiment that would speedily sweep him from his own throne, De Terney would no doubt have stayed at home and Rochambeau’s descendants would not now be coming to America to celebrate his victories.

But, happily for us, the king had not the gift of prevision. Whether he did it of his own accord, or whether the revolutionary tide was already too strong, he dispatched the troops without whose aid the colonies might not have secured their independence.

Although they left France in April it was not until the 10th of July that they reached the American coast.

Their destination was Newport, but it must have seemed to the sea-tossed voyagers as though Newport were the fabulous Isle of St. Branden, which sank beneath the waves when anyone sought to find it.

Storms drove them from their course, head-winds kept them back, English cruisers chased them away from port, and, worse than all, they fell ill by hundreds with the scurvy.

Had the voyage lasted much longer there might have been no army left.

Finally, however, they sighted the Rhode Island shore at Point Judith, and although in our day the place bears an inhospitable name, to the sick and weary Frenchmen it must have been a most inviting haven.

What made it more inviting was the discovery, as the fleet drew near, of the white flag of France, bearing the golden fleur de lis, which had been raised above the rocks to assure them that the country was not in unfriendly hands, and that they might safely make the journey up to Newport.

Their arrival was hailed with joy. No part of the colonies had suffered more than Rhode Island. Newport, prior to the war one of the most prosperous of the colonial towns, had experienced great losses both in wealth and population.

The surrounding country had been stripped of trees for firewood for the armies. Once a garden, it had become bare and desolate.

Now, under the protection of the French, it was hoped that it might have a chance to revive. The houses accordingly were illuminated, the officers were welcomed to the homes of the people, and that series of fetes, receptions and dinners begun which has made the French occupation of Rhode Island one of the most brilliantly picturesque episodes in American History.

It was not long before the people became warmly attached to their new guests, whose elegant manners and thoughtful consideration contrasted strikingly with the rude arrogance of the British.

“The French officers of every rank” writes one from Providence at that time, “have rendered themselves agreeable by their politeness, which characterizes the French nation.”

On the French themselves the Americans seem to have made scarcely as favorable an impression.

One of Rochambeau’s aids—a young Swede named De Fersen—writes home to his father in terms that are the reverse of complimentary:

“The spirit of patriotism,” he says, “only exists in the chief and principal men in the country, who are making very great sacrifices. The rest, who make up the great mass, think only of their personal interest. Money is the controlling idea in all their actions. They only think of how it may be gained. Everyone is for himself; no one for the general good.

“The inhabitants of the coast, even the best Whigs, carry to the English fleet, anchored in Gardner Bay, provisions of all kinds, and this because they are well paid. They overcharge us mercilessly. Everything is enormously dear.

“In all the dealings we have had with them they have treated us more like enemies than friends. Their greed is unequaled; money is their God ; virtue, honor, all count for nothing to them compared with the precious metal. I do not mean that there are no estimable people, of noble and generous character.

“There are many; but I speak of the nation in general. I believe that they are more like the Dutch than the English.”

On the other hand, De Fersen’s superior—Count de Rochambeau himself—bears witness to the patriotism of the people in the story of a Wheelwright whom he desired to mend his carriage, but who declined on the ground that he was sick with ague and would do no work at night, “not even for a hatful of guineas.”

Rochambeau went in person to the man’s shop, told him that General Washington would arrive at Hartford the same evening, to confer with the French the following day, and that unless the carriage were repaired they would be too late to meet him.

“You are no liars, at any rate,” the man replied, “for I read in the Connecticut paper that Washington was to be there to confer with you. As it is for the public service I will take care that your carriage shall be ready for you at six in the morning.”

The man kept his word; and Rochambeau adds: “I do not mean to compare all Americans to this good man, but almost all the inland cultivators and all the land-owners of Connecticut are animated with that patriotic spirit which many other people would do well to imitate.”

While the Americans were naturally elated at the arrival of the French, the Tory sympathizers were correspondingly depressed, and artfully sought to create the impression that the movement was only preliminary to a seizure of the country by the King of France.

“The Chevalier de Terney,” says Rivington’s “ Royal Gazette”—the Tory organ at that time in New York—“may be expected at this time to land a body of troops on this continent, in which case possession of the land would be taken in the name of the French king.

“However, in this intention they probably will be molested by a power that has hitherto often proved too mighty for the united House of Bourbon. The prospect of a French army landing in the northern provinces alarms the republican fraternity in Connecticut and Massachusetts.

“Should their Roman Catholic allies ever nestle themselves on one of the revolted States it is apprehended their independence must give way to the establishment of a French government, laws, customs, etc., ever abhorrent to the sour and turbulent temper of the Puritan.”

This was July 16th, before the news of the landing of the troops at Newport had reached New York.

Under date of August 2d, the same paper adds:

“The French admiral has taken possession of Rhode Island in the name of the King of France, and displayed the French colors without the least deference to the flag of their ally, the revolted Americans.

“This affords disgust and mortification to the rebels, evincing that their Roman Catholic friends intend to keep possession of all they seize on in North America.”

Journalism, it seems, even at that early day had little to learn in the way of misrepresentation and deceit.

Whether or not these insinuations had any effect there is no doubt that for some time after the arrival of the French Washington was unfavorably disposed toward them, and did not grant Rochambeau the personal interview he desired until after he had publicly disavowed any intention of exercising independent authority, and declared that he and his troops were subject to General Washington’s command.

Even when they had met, as they did at Hartford, September 20th, Washington does not seem to have been wholly reconciled. Under date of January 14, 1781, De Fersen writes, “There is a coolness between Washington and M. Rochambeau.

“The dissatisfaction is on the part of the American general. Ours is ignorant of the reason.

“He has given me orders to go with a letter from him and to inform myself of the reason for his discontent – to heal the breach if possible, or, if the affair be more grave, to report to him the cause.”

De Fersen does not, state whether he ascertained the cause of the coolness but it is more than likely that it was due to the tardiness of Rochambeau in taking any steps that looked to a forward movement.

De Fersen himself expresses his own displeasure and that of the French officers at the long delay.

“We have been long enough,” he writes May 17, 1781; “in inaction—in shameless inaction. It would have been of more use to the Americans to have sent out the money which we have cost the king here. They would have employed it to better purpose.”

The event, however, seems to have justified Rochambeau’s policy.

The situation was a grave one; no more supplies could be expected from France; the destinies of the conflict hinged upon the blow that he should strike, and it was of the last importance that he should strike it under the most favorable conditions.

In the spring of 1781, for the first time since Rochambeau‘s arrival, the conditions seemed promising.

The British army had been effectually divided by Cornwallis’s Southern expedition, and Cornwallis himself was likely to be entrapped in Virginia.

At the very time when De Fersen was making his sharpest criticism, Rochambeau was arranging with General Washington for an interview in which a plan of operations should be adopted.

The meeting was held at Wethersfield, Conn., May 22d, and resulted in a mutual understanding.

Washington’s idea, as disclosed at the interview, was to make New York the point of attack, concentrating there the entire French and American force.

Rochambeau, who had in mind the cooperation of the French fleet, then in the West Indies, preferred to carry the troops to Virginia and there attack the army of Cornwallis, already held in check by Lafayette.

A final determination between the two plans was left until after the French troops should have joined Washington’s army on the Hudson River —a movement which Rochambeau at once proceeded to effect.

Accordingly, on the 9th of June, the French made their exit from Newport.

Their route led them across the country through the towns of Plainfield, Canterbury, Windham, Bolton, Hartford, Farmington, Southington, Newtown, Ridgebury, Bedford, North Castle and White Plains, where they arrived on the 5th of July.

Here, or in this neighborhood, they remained until August 19th, when suddenly the camp was again broken, the army transported across the Hudson at King’s Ferry, and marched southward through the villages of Pompton, Chatham and Morristown, New Jersey.

At the start no one beyond the commanding officer and a few of his intimates had the slightest idea where the army was bound.

It was generally believed that an attack was meditated upon New York from the Jersey side, and this idea was confirmed in the English mind by an intercepted letter from the Chevalier de Chastellux to the French representative at Congress, “wherein,” says Rochambeau, “he boasted of having artfully succeeded in bringing round their opinion to concur with that of General Washington, stating, at the same time, that the siege of the island of New York had been at length determined upon, and that our two armies are on the March for that city, and that orders had been sent off to M. de Grasse to come with his fleet and force his way over the bar of Sandy Hook to the mouth of the harbor of New York.”

Not till the army arrived at Princeton did it become known that its destination was Virginia, and that the plan which had finally been decided upon was to attack Cornwallis in concert with the fleet of De Grasse.

The troops, spurred by the change of base, and the assurance that definite action was at length to be taken, pushed on with renewed vigor.

It was now too late for General Clinton, the British commander at New York, to make any effort to overtake them, and, without fear of attack or hindrance, they pursued their march through Trenton to Philadelphia.

Here the army was reviewed by the Continental Congress, and the elegant presence of the French troops in their white uniforms and parti-colored trimmings is said to have made a profound impression upon the spectators.

It was at Chester, a short distance out of Philadelphia, that the army learned of De Grasse’s safe arrival in the Chesapeake, and that the only factor which had hitherto seemed wanting to the complete success of their undertaking was now supplied.

The delight of Washington on receiving this gratifying news is said to have been in striking contrast to the ordinary coolness and imperturbability of his nature.

“I have been equally surprised and touched,” writes the Count de Deuxpont, alluding to this occurrence, “at the true and pure joy of General Washington. Of a natural coldness and of a serious and noble approach, which in him is only true dignity, and which adorns so well the chief of a whole nation, his features, his physiognomy, his deportment—all were changed in an instant. He put aside his character as Arbiter of North America, and contented himself with that of a citizen, happy at the good fortune of his country. A child whose every wish had been gratified would not have experienced a sensation more lively; and I believe that I am doing honor to the feelings of this rare man in endeavoring to express all their ardor.”

Washington’s character, indeed, was a continual study to the French generals, and the favorable impression which he made upon them seems to have been deep and permanent.

From Chester the army took its way to Annapolis, and at this point De Grasse’s transports were in readiness to carry the troops to the James, where Lafayette was already awaiting their arrival.

=====

The Washington Bicentennial Quarter Coin shows against an artist’s image of the French landing at Rhode Island in July 1780.