Today, the Morgan Silver Dollar Coin remembers when the explorer, Henry Stanley, told of his many adventures to the Lotos Club in New York on November 27, 1886.

The New York Tribune newspaper of November 28, 1886 provided a lengthy description of Mr. Stanley’s tales of his explorations:

=====

The Explorer Tells of His Adventures —

Henry M. Stanley, the African explorer, was entertained at dinner by the Lotos Club last night. Fourteen years ago, when he had Just returned from Africa after having found Livingstone, the same club had Stanley for its guest.

Shortly before 9 o’clock, the President rose and called for order.

All honor to our returning guest! The years have left their marks upon his frame and their honors upon his name. Let us make him forget the fevers that have parched him, the wild beasts and the more savage men that have pursued him. [“Hear! hear!”] He is once more among the friends of his youth, in the land of his adoption. Let us make him feel at home. [Applause.] I give you the health of our friend and comrade. [Applause.]

Mr. Stanley on rising to respond was received with prolonged cheering, and it was some moments before he could be heard. When the demonstration came to an end he said:

Mr. Chairman and Gentlemen of the Lotos Club:

One might start a great many principles and ideas which would require to be illustrated and drawn out in order to present a picture of my feelings at the present moment. I am conscious that in my immediate vicinity there are people who were great when I was little. I remember very well, when I was unknown to anybody, how I was sent to report a lecture by my friend right opposite, Mr. George Alfred Townsend [applause], and I remember the manner in which he said, “Galileo said, ‘The world moves round,’ and the world does move round,” upon the platform of the Mercantile Hall in St. Louis— one of the grandest things out! [Laughter and applause]

The next great occasion when I had to come before the public was Mark Twain’s lecture on the Sandwich Islands, which I was sent to report. And when I look to my left here I see Colonel Anderson, whose very face gives me an idea that Bennett has got some telegraphic dispatch and is just about to send me to some terrible region for some desperate commission. [Laughter]

And of course you are aware that it was owing to the proprietor and editor of a newspaper that I dropped the pacific garb of a journalist and donned the costume of an African traveler. It was not for me, one of the least in the newspaper corps, to question the newspaper proprietor’s motives. He was an able editor, very rich, desperately despotic. [Laughter.]

He commanded a great army of roving writers, people of fame in the news-gathering world; men who had been everywhere and seen everything, from the bottom of the Atlantic to the top of the very highest mountain; men who were as ready to give their advice to National Cabinets [Laughter] as they were ready to give it to the smallest police-courts in the United States. [Laughter.]

I belonged to this class of roving writers, and can truly say that I did my best to be conspicuously great in it [laughter] by an untiring devotion to my duties, an untiring indefatigability, as though the ordinary rotation of the universe depended upon my single endeavors. [Laughter.]

If as some of you suspect, the enterprise of the able editor was only inspired with a view to obtain the largest circulation [laughter] my unyielding and guiding motive, if I remember rightly, was to win his favor by doing with all my might that duty to which, according to the English State Church catechism it had pleased God to call me. [Laughter and applause.]

He first dispatched me to Abyssinia—straight from Missouri to Abyssinia! [Laughter.] What a stride, gentlemen! [Renewed laughter.]

People who live west of the Missouri River have scarcely, I think, much knowledge of Abyssinia, and there are gentlemen here who can vouch for me in that.

But it seemed to Mr. Bennett a very ordinary thing and it seemed to his agent in London a very ordinary thing indeed. [Laughter.] So I, of course, followed suit. I took it as a very ordinary thing also, and I went to Abyssinia and somehow or another good luck followed me, and my telegrams reporting the fall of Magdala happened to be a week ahead of the British Government’s.

The people said I had cone right well, though the London papers said I was an imposter. [Laughter.] The second thing I was aware of was that I was ordered to Crete, to run the blockade, describe the Cretan rebellion from the Cretan side and from the Turkish side; and then I was sent to Spain to report from the Republican side and from the earliest side, perfectly dispassionately. [Laughter.]

And then all of a sudden I was sent for to come to Paris.

Then Mr. Bennett, in that despotic way of his, said: “I want you to go and find Livingstone.”

As I tell you, I was a mere newspaper reporter. I dared not confess my soul as my own. Mr. Bennett merely said “Go,” and I went. He gave me a glass of champagne and I thought that was superb. [Laughter.]

I confessed my duty to him, and I went. And as good luck would have it. I found Livingstone. [Loud and continued cheering.]

I returned as a good citizen ought, and as a good reporter ought, and as a good newspaper correspondent ought, to tell the tale, and arriving at Aden, I telegraphed a request that I might be permitted to visit civilization before I went to China. [Laughter.]

I came to civilization; and what do you think was the result? Why, only to find that all the world disbelieved my story. [Laughter.]

Dear me! If I were proud of anything, sire, it was that what I said was a fact [“Good!”]; that whatever I said I would do, I would endeavor to do with all my might, or, as many a good man had did before, as my predecessors had done, lay my bones behind. That’s all. [Loud cheers.]

I was requested, in an off-hand manner—just as any member of the Lotos Club here present would say— “Would you mind giving us a little resume of your geographical work?” I said: “Not in the least, my dear sir; I haven’t the slightest objection.”

And do you know that to make it perfectly geographical and not in the least sensational I took particular pains and I wrote a paper out, and when it was printed it was just about so long [indicating and inch].

It contained about a hundred polysyllabic African words. [Laughter.] And yet “for a’ that and a’ that,” the pundits of the Geographical Society, the Brighton Association, said that they hadn’t come to listen to any sensational stories, but that they had come to listen to facts. [Laughter.]

Well, now, an old gentleman, very reverend, full of years and honors, learned in Cufic inscriptions and cunieform characters, wrote to The Times, stating that it was not Stanley who had discovered Livingstone, but that it was Livingstone who had discovered Stanley. [Laughter.]

Mr. Stanley then alluded to the unbelief in his discoveries prevailing at that time in New York, and continued:

If it had not been for that unbelief, I don’t believe I should ever have visited Africa again. I should have become, or I should have endeavored to become, with Mr. Reid’s permission, a conservative member of the Lotos Club. [Laughter.]

I should have settled down and become as steady and as stolid as some of these patriots that you have around you here. I should have said nothing offensive. I should have done some “treating.” I should have offered a few a cigar, and on Saturday night, perhaps, I would have opened a bottle of champagne and distributed it among my friends. But that was not to be.

I left New York for Spain, and then the Ashantee War broke out, and once more my good luck followed me, and I got the treaty of peace ahead of everybody else, and as I was coming to England from the Ashantee War a telegraphic dispatch was put into my hands at the Island of St. Vincent saying that Livingstone was dead!

I said: “What does that mean to me? The New Yorkers don’t believe in one. How shall I prove that what I have said is true? By George! I will go and complete Livingstone’s work. I will prove that the discovery of Livingstone was a mere flea-bite. I will prove to them that I am a good man and true.”

That’s all that I wanted. [Loud cheers.] I accompanied Livingstone’s remains to Westminster Abbey. I saw those remains buried which I had left sixteen months before enjoying full life and abundant hope. The Daily Telegraph’s proprietor cabled over to Bennett: “Will you join us in sending Stanley over to complete Livingston’s explorations?”

Bennett received the telegram in New York, read it, pondered a moment, snatched a blank and wrote, “Yes. Bennett.”

That was my commission and I set out to Africa, intending to complete Livingstone’s explorations, also to settle the Nile problem as to where the headwaters of the Nile were, as to whether Lake Victoria consisted of one lake, one body of water, or a number of shallow lakes; to throw some light on Sir Samuel Baker’s Albert Nyanza, and also to discover the outlet of Lake Tanganyika, and then to find out what strange, mysterious river this was which had lured Livingstone on to his death — whether it was the Nile, the Niger or the Congo.

Edwin Arnold, the author of “The Light of Asia,” said, “Do you think you can do all this?”

“Don’t ask me such a conundrum as that. Put down the funds and tell me to go. That’s all.” [Hear! Hear!] And he induced Lawson, the proprietor, to consent. The funds were had and I went.

First of all, we settled the problem of the Victoria; that it was one body of water; that instead of being a cluster of shallow lakes or marshes, it was one body of water, 21,500 square miles in extent.

While endeavoring to throw light upon Sir Samuel Baker’s Albert Nyanza, we discovered a new lake, a much superior lake to the Albert Nyanza — the Dead Locust Lake — and at the same time Gordon Pacha sent his lieutenant to discover and circumnavigate the Albert Nyanza, and he found it to be only a miserable 140 miles, because Baker, in a fit of enthusiasm, had stood on the brow of a high plateau and, looking down on the dark blue waters of the Albert Nyanza, cried romantically: “I see it extended indefinitely toward the southwest!”

“Indefinitely” is not a geographical expression, gentlemen. [Laughter.]

We found that there was no outlet to the Tanganyika, although it was a sweet water lake. After settling that problem, day after day, as we glided down the strange river that had lured Livingstone to his death, we were in as much doubt as Livingstone had been when he wrote his last letter and said: “I will never be mad black man’s meat for anything less than the classic Nile.”

After traveling 400 miles we came to the Stanley Falls, and beyond them we saw the river deflect from its Nileward course toward the Northwest. Then it turned west, and then visions of towers and towns and strange tribes and strange nations broke upon our imagination, and we wondered what we were going to see, when the river suddenly took a decided turn toward the southwest and our dreams were put an end to.

We saw then that it was aiming directly for the Congo, and when we had propitiated some natives whom we encountered by showing them crimson beads and polished wire that had been polished for the occasion [laughter], we said: “This for your answer. What river is this?”

“Why, it is the river, of course.” That was not an answer, and it required some persuasion before the chief, bit by bit, digging into his brain, managed to roll out sonorously the words: “It is the Ko-to-yah Congo” — “It is the river of Congoland.”

Alas for our classic dreams! Alas for Crophi and Mophi, the fabled fountains of Herodotus! Alas for the banks of the river where Moses was found by the daughter of Pharaoh. This is the parvenu Congo!

Then we glided on and on, past strange nations and cannibals — not past those nations which have their heads under their arms [laughter] for 1,100 miles, until we arrived at a circular extension of the river and my last remaining companion called it the Stanley Pool, and then, five months after that, our journey ended.

After that I had a very good mind to come back to America and say, like the Queen of Uganda, “There, what did I tell you?”

But you know the fates would not permit me to come over in 1878. The very day I landed in Europe, the King of Italy gave me an express train to convey me to France, and the very moment I descended from it at Marseilles, there were three ambassadors from the King of the Belgians, asking me to go back to Africa.

“What! Back to Africa? Never! [Laughter.] I have come for civilization. I have come for enjoyment. I have come for love, for life, for pleasure. Not I. Go and ask some of those people you know who have never been to Africa before. I have had enough of it.”

“Well, perhaps, by and by—”

“Ah, I don’t know what will happen by and by, but, just now, never, never! Not for Rothschild’s wealth!” [Laughter and applause.]

I was received by the Paris Geographical Society, and it was when I begun to feel, “Well, after all, I have done something, haven’t I!”

I felt superb. [Laughter.] But you know I have always considered myself a republican. I have those bullet riddled flags and those arrow torn flags, the Stars and Stripes that I carried in Africa for the discovery of Livingstone and that crossed Africa, and I venerate those old flags. I have them In London now jealously guarded in the secret recesses of my cabinet. I allow only my very best friends to look at them, and if any of you gentlemen ever happen in at my quarters I will show them to you. [Applause.]

After l had written my book, “Through the Dark Continent,” I began to lecture, using these words: “I have passed through a land watered by the largest river of the African continent, and that land knows no owner. A word to the wise is sufficient.

You have cloths and hardware and glassware and gunpowder, and those millions of natives have ivory and gums and rubber and dyestuffs and in barter there is good profit!” [Laughter.]

The King of the Belgians commissioned me to go to that country. My expedition when we started from the coast numbered 300 colored people and 14 Europeans. We returned with 3,000 trained black men and 300 Europeans. The first sum allowed me was $50,000 a year, but it has ended at something like $700,000 a year. Thus you see the progress of civilization.

We found the Congo having only canoes. Today, there are eight steamers. It was said at first that King Leopold as a dreamer. He dreamed he could united the barbarians of Africa into a confederacy and call it a free state; but on February 25, 1885, the Powers of Europe, and America also, ratified an act recognizing the territories acquired by us to be the free and independent State of the Congo.

Perhaps when the members of the Lotos Club have reflected a little more upon the value of what Livingstone and Leopold have been doing, they will also agree that these men have done their duty in this world and in the age that they live, and that their labor has not been in vain on account of the great sacrifices they have made to the benighted millions of dark Africa. [Loud and enthusiastic applause.]

=====

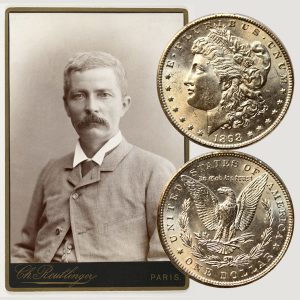

The Morgan Silver Dollar Coin shows with an image of Henry Stanley, circa 1884.