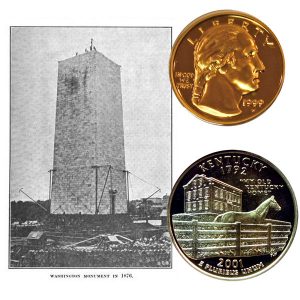

Today, the Kentucky State Quarter Coin and the Washington Gold Five-Dollar Coin remember when the legislature agreed, on January 24, 1850, to provide one of the blocks of marble for the monument overlooking the Potomac.

From Acts Passed at the Session of the General Assembly for the Commonwealth of Kentucky, published in 1850:

=====

No. 5.

Resolution providing a block of marble for the “Washington Monument.”

Resolved, by the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, That the Governor be and he is hereby authorized and requested to cause a suitable block of native marble to be conveyed to Washington city, to take its proper place in the Monument now being erected to the memory of the “Father of his Country,” and that the following words be engraved thereon: “Under the auspices of Heaven and the precepts of Washington, Kentucky will be the last to give up the Union.”

Approved January 24, 1850.

=====

An excerpt of the article, Inscribed Stones in the Washington Monument, by Arthur C. Cole, published in The History Teacher’s Magazine of March 1812:

=====

A crisis was occurring in the history of the republic; secession and civil war were threatening to involve the nation in the bloody struggle that was only delayed for another decade.

The South, dissatisfied with the treatment of her rights and institutions in the Union, was thinking of severing the bonds that held her to it.

An overwhelming majority of the citizens of South Carolina were in favor of the dissolution of the Union, believing that the South would be benefited both pecuniarily, politically, and morally.

One of her most prominent leaders, and a later United States Senator, declared the Union to be “a splendid failure of the first modern attempt by people of different institutions, to live under the same government.”

Such sentiment was not confined to South Carolina alone, but was expressed all over the lower South. These states, through their legislatures, through state constituent conventions, and even acting in a convention of the slaveholding states, seriously considered the expediency of secession and withdrawal from the compact of the federal Constitution.

Even when the compromise acts of 1850 were adopted as measures of pacification to check the tide of agitation, it was found that they only incited the secession element in the South to a greater determination to safeguard the interests of that section and to a greater readiness to resort to disunion.

The Union men labored hard to check this sentiment but for a time the odds were against them. The executives of South Carolina, Georgia, and Mississippi, themselves of the opinion that now was the time to act, advised preparations for armed resistance when the issue should be made.

Book-dealers in Philadelphia, New York, and Boston, noted an unprecedented sale of works on military tactics to southern buyers.

The militia of South Carolina was carefully equipped and drilled under the Palmetto flag.

The Mississippi legislature even refused to allow the Stars and Stripes to be unfurled over the state capitol where it was deliberating.

The call upon the various states for blocks of stone to the memory of Washington came inevitably, though unintentionally as an appeal for the preservation of the Union.

It recalled to loyal citizens the counsel of his farewell address to frown at the first dawnings of any movement to alienate one portion of the country from another, with “Union” as the first, the last, the constant strain of his immortal words.

They saw the full-orbed comet of disunion shooting athwart the political firmament, disturbing the harmony of our system, and threatening to throw it into chaos.

At no previous period had the nation been more imperiously called on to rally around the principles of Washington and to refresh their recollections with his parting words of counsel and advice.

Indeed several prominent and patriotic citizens proposed to make Washington’s farewell address a text-book of sound political truth for all time, to be turned to when any new course of action is proposed and doubts entertained of its propriety, and of its safety to the honor and prosperity of the republic.

The Union element of the Mississippi legislature answered the printing of a large number of copies of Governor Quitman’s disunion message by forcing through a resolution ordering the printing of fifteen thousand copies of the farewell address.

At no previous period had Washington’s precepts and the great lesson of his life been more generally appealed to than in the two years of 1850 and 1851, when the danger of disunion was doubtless greater than at any other time in the early history of the Republic.

Pilgrimages were made to his grave at Mount Vernon, his name was toasted as the watchword against disunion, his memory was the pillar of fire that guided the nation through that crisis.

“It is hardly extravagant to say,” declared one of the leading newspapers of the day on the anniversary of his birth, “that, had it not been for the commanding authority of that honored name, and its historical associations, in favor of national and conservative principles, this Confederacy the fruit of the counsels of WASHINGTON, and in part the work of his hands, might before this time have been broken up in the violence of the conflict, which has been raging between men of obstinate prejudices and extreme opinion, upon questions of purely internal administration. . . . If that danger is now happily passing away, we are in a great degree indebted for our escape from it to the moral as well as the political influence of the memory of WASHINGTON.”

As is to be expected, the national monument project became a popular one amid these conditions.

Generous contributions came in from all sides, from citizens in their private capacity, from the Masonic and Odd Fellow orders, from temperance societies, from schools and colleges, from Indian tribes, and from every possible source.

Assemblies were held at the base of the monument on each succeeding Fourth of July to listen to the speeches of distinguished visitors.

It was while at such a gathering in 1850, the monument then being fifty feet high, that President Taylor contracted his sudden and fatal illness from exposure to the midday heat while listening to a powerful appeal for the Union, by Senator Foote, of Mississippi.

A craze for monument building developed in these years.

Virginia began her famous one to Washington at Richmond, the project for a monumental column at Yorktown was taken up with enthusiasm, and Congress at length made an appropriation of fifty thousand dollars to carry into execution the resolution of 1783 for the erection of a bronze equestrian statue of Washington.

It was even proposed to erect one to commemorate his achievements at Fort Necessity.

Meantime, the work on the obelisk overlooking the Potomac went on apace.

Within a few years it grew to the height of one hundred and fifty feet. The states had made a prompt response to the appeal to their affection for the Father of his Country.

From them came the massive blocks—more significant by far than the stones from Switzerland, Rome, Turkey, Greece, or even far China and Japan—inscribed with words of affectionate devotion to the Union as the best mode of expressing the reverence with which they cherished his memory, that we now see on the landings of the staircase within the monument.

Michigan sent a block of native copper as “AN EMBLEM OF HER TRUST IN THE UNION”; Ohio inscribed upon a marble stone the legend, “THE MEMORY OF WASHINGTON AND THE UNION OF THE STATES, SUNTO PERPETUO.” “INDIANA— KNOWS NO NORTH, NO SOUTH, NOTHING BUT THE UNION.”

This sentiment was answered by Massachusetts, “OUR COUNTRY IS SAFE WHILE THE MEMORY OF WASHINGTON IS REVERED.”

Maryland sent a marble block, “THE MEMORIAL OF HER REGARD FOR THE FATHER OF HIS COUNTRY, AND OF HER CORDIAL, HABITUAL, AND IMMOVABLE ATTACHMENT TO THE AMERICAN UNION,” a sentiment similar to that of Kentucky,— “UNDER THE AUSPICES OF HEAVEN AND THE PRECEPTS OF WASHINGTON, KENTUCKY WILL BE THE LAST TO LEAVE THE UNION.”

Louisiana patriotically inscribed the words,—”THE STATE OF LOUSIANA, EVER FAITHFUL TO THE CONSTITUTION.”

The other southern states were more equivocal in their expressions.

Alabama praised “A UNION OF EQUALITY AS ADJUSTED BY THE CONSTITUTION”; Mississippi sent a stone with the simple inscription, “TO THE FATHER OF HIS COUNTRY.”

Proud South Carolina and several others inscribed merely their coat of arms.

The bitterness of feeling against the Palmetto state was evidenced when the figures on her coat of arms were mutilated after the block reached Washington—the work of some mad fanatic.

On the fifty foot landing one finds the Georgia stone bearing the legend: “THE CONSTITUTION AS IT IS, THE UNION AS IT WAS,” an enigma to the tourist who does not understand the history of this period. This was inscribed under the influence of Governor Towns, who in calculating the value of the Union had come to believe that it had become disadvantageous and perhaps undesirable to the South.

The Georgia constituent convention of December, 1850, however, dominated by Union men, counteracted the importance of his action by sending in a block devoid of a hostile sentiment, and a later legislature ordered the original stone replaced by one bearing the arms of the state. This, however, appears never to have been done.

In 1852, it was noticed that the collection of contributions had begun to decline.

In March of that year, when the monument was one hundred and five feet high, the society appealed to the American people stating that unless contributions became larger and more numerous than they had been in the last six months, it would be impossible to continue the work further.

By that time the crisis had passed and the danger of disunion was temporarily removed. The Society now began to resort to new expedients to raise funds. Collection boxes were placed at the polls on election days labeled “A DIME TO THE MEMORY OF WASHINGTON,” to encourage subscriptions on the democratic basis that had thus far been the feature of the movement.

Now, however, new by-laws were adopted making the contributor of twenty-five dollars a member and of one hundred dollars eligible to the office of vice-president of the society.

A special role of honor was provided for donors of from one hundred to one thousand dollars, whose names were to be inscribed in panels within the monument indicating the size of their gift.

The Sons of Temperance of the United States are said to have made a proposition to complete the monument, it being supposed that the work could be accomplished in five years by each member of the order paying five cents a week. If this rumor was based on fact, nothing came of the suggestion.

The Board of Managers next appealed to the clergymen to stir up the people on the Fourth of July, which happened to fall on Sunday, and suggested special collections in the churches for this great and patriotic object.

The funds raised by these efforts made it possible for the work on the monument to continue until it rose to a height of one hundred and fifty feet.

=====

The Kentucky State Quarter Coin and the Washington Gold Five-Dollar Coin show with an image of the early work on the monument in 1876.