Today, the Standing Liberty Gold Quarter Coin remembers when the Bostonians took a stance for freedom in a meeting 244 years ago about tea.

From Tea Leaves, Being a Collection of Letters and Documents Relating to the Shipment of Tea to the American Colonies in the Year 1773, by the East India Tea Company, compiled by Francis S. Drake, published in 1884:

=====

On Sunday, the 28th, the ship “Dartmouth,” Captain Hall, owned by the Quaker, Francis Rotch, arrived in Boston harbor, with one hundred and fourteen chests of tea, and anchored below the castle.

As the news spread, there was great excitement. Despite the rigid New England observance of the Sabbath, the selectmen immediately met, and remained in session until nine o’clock in the evening, in the expectation of receiving the promised proposal of the consignees.

These gentlemen were not to be found, and on the next day, bidding a final adieu to Boston, they took up their quarters at the castle.

Hutchinson advised the consignees to order the vessels, when they arrived, to anchor below the castle, that if it should appear unsafe to land the tea, they might go to sea again, and when the first ship arrived she anchored there accordingly, but when the master came up to town, Mr. Adams and others, a committee of the town, ordered him at his peril to bring the ship up to land the other goods, but to suffer no tea to be taken out.

The committee of correspondence, who also held a session that day, seeing that time was precious, and that the tea once entered it would be out of the power of the consignees to send it back, obtained the promise of the owner not to enter his ship till Tuesday, and authorized Samuel Adams to summon the committees and townspeople of the vicinity to a mass meeting, in Boston, on the next morning.

The invitation read as follows: “A part of the tea shipped by the East India Company is now arrived in this harbor, and we look upon ourselves bound to give you the earliest intimation of it, and we desire that you favor us with your company at Faneuil Hall, at nine o’clock tomorrow forenoon, there to give us your advice what steps are to be immediately taken, in order effectually to prevent the impending evil, and we request you to urge your friends in the town, to which you belong, to be in readiness to exert themselves in the most resolute manner, to assist this town in its efforts for saving this oppressed country.”

The journals of Monday announced that the “Dartmouth” had anchored off Long Wharf, and that other ships with the poisonous herb might soon be here.

They also contained a call for a public meeting, as announced in the following handbill, already printed and distributed throughout the town:

“Friends! Brethren! Countrymen! That worst of plagues, the detested tea, shipped for this port by the East India Company, is now arrived in this harbor; the hour of destruction or manly opposition to the machinations of tyranny stares you in the face; every friend to his country, to himself, and posterity, is now called upon to meet at Faneuil Hall, at nine o’clock this day, (at which time the bells will ring,) to make a united and successful resistance to this last, worst and most destructive measure of administration. Boston, November 29, 1773.”

At nine o’clock the bells were rung, and the people, to the number of at least five thousand, thronged in and around Faneuil Hall.

This edifice, then about half as large as now, was entirely inadequate to hold the concourse that had gathered there.

Jonathan Williams, a citizen of character and wealth, was chosen moderator. The selectmen were John Scollay, John Hancock, Timothy Newell, Thomas Newhall, Samuel Austin, Oliver Wendell, and John Pitts. The patriotic and efficient town clerk, William Cooper, was also present.

Samuel Adams, Dr. Warren, Hancock, Dr. Young and Molineux took the lead in the debate.

The resolution offered by Adams, “that the tea should not be landed; that it should be sent back in the same bottom to the place whence it came, at all events, and that no duty should be paid on it,” was unanimously adopted.

On hearing of this vote the consignees withdrew to Castle William.

For the better accommodation of the people, the meeting then adjourned to the Old South Meeting House.

The speeches made at the Old South have not been preserved. Some were violent, others were calm, advising the people by all means to abstain from violence, but the men in whom they placed confidence were unanimous upon the question of sending back the tea.

Dr. Young held that the only way to get rid of it was to throw it overboard. Here we find the first suggestion of its ultimate fate.

Both Whigs and Tories united in the action of the meeting. To give the consignees time to make the expected proposals, the meeting adjourned till three o’clock.

Of this assembly Hutchinson says: “Although it consisted principally of the lower ranks of the people, and even journeymen tradesmen were brought to increase the number, and the rabble were not excluded, yet there were divers gentlemen of good fortune among them.”

With regard to the speeches he observes: “Nothing can be more inflammatory than those made on this occasion; Adams was never in greater glory.”

And of the consignees he says: “They apprehended they should be seized, and may be, tarred and feathered and carted, — an American torture, — in order to compel them to a compliance. The friends of old Mr. Clarke, whose constitution being hurt by the repeated attacks made upon him, retired into the country, pressed his sons and the other consignees to a full compliance.”

A visitor from Rhode Island who attended the meeting, speaking of its regular and sensible conduct, said he should have thought himself rather in the British senate than in the promiscuous assembly of the people of a remote colony.

At the afternoon meeting in the Old South, it was resolved, upon the motion of Samuel Adams, “that the tea in Captain Hall’s ship must go back in the same bottom.”

The owner and the captain were informed that the entry of the tea, or the landing of it, would be at their peril.

The ship was ordered to be moored at Griffins’ wharf, and a watch of twenty-five men was appointed for the security of vessel and cargo, with Captain Edward Proctor as captain that night.

It was also voted that the governor’s call on the justices to meet that afternoon, to suppress attempted riots, was a reflection on the people.

Upon Hancock’s representation that the consignees desired further time to meet and consult, the meeting consented, “out of great tenderness to them,” and adjourned until next day.

This meeting also voted that six persons “who are used to horses be in readiness to give an alarm in the country towns, when necessary.”

They were William Rogers, Jeremiah Belknap, Stephen Hall, Nathaniel Cobbett, and Thomas Gooding, and Benjamin Wood, of Charlestown.

The guard for the tea ships, which consisted of from twenty-four to thirty-four men, was kept up until December 16.

It was armed with muskets and bayonets, and proceeded with military regularity, — indeed it was composed in part of the military of the town, — and every half hour during the night regularly passed the word “all’s well,” like sentinels in a garrison.

It was on duty nineteen days and twenty- three hours.

If molested by day the bells of the town were to be rung, if at night they were to be tolled.

=====

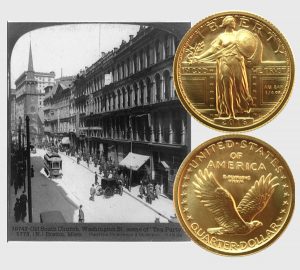

The Standing Liberty Gold Quarter Coin shows with an image of the Old South Meeting Hall, circa 1910.