Today, the Maine Commemorative Silver Half Dollar Coin remembers when the first bridge of the area fell on June 23, 1816.

Rather than uniting the two villages across the river, this bridge divided Fort Western and Hook for years.

From the Illustrated History of Kennebec County, Maine; edited by Henry D. Kingsbury and Simeon L. Deyo, published in 1892:

=====

But the year 1796 saw the inception of an enterprise that was to settle finally the question of supremacy between the villages and radically affect the future careers of both.

The Kennebec river was a natural impediment between the two parts of the upper village. Pollard’s ferry had been run since 1785, from the foot of Winthrop street (then called Winthrop road) to the fort landing opposite.

Now the citizens of Fort Western daringly undertook to supplant this ferry with a bridge. The proposition provoked great consternation at the Hook.

The Fort Western people’s petition for a charter was duly presented to the legislature. The Hook people appointed Charles Vaughan their agent to resist it. But Daniel Cony being a senator and James Bridge a member of the house (both Fort Western men of great influence), the opposition of the Hook and its endeavor to divert the location of the proposed bridge to that place were of no avail.

The act incorporating the proprietors of the Kennebec bridge was passed February 8, 1796. The corporators — the foremost men of the village — were: Samuel Howard, William Howard, Joseph North, Daniel Cony, Jedediah Jewett, Samuel Dutton, William Brooks, Matthew Hayward, James Bridge.

It was a stipulation in the charter that the bridge should be located “between the ferry called Pollard’s ferry [now the town-landing] and the Mill stream [Bond’s brook] so called, which empties into Kennebec river about one hundred rods north of said ferry.”

Subscription books were immediately opened, shares were promptly taken, and the work of construction pushed forward with great energy. A Captain Boynton was the architect.

On the 9th of September, 1797, the completion of the pier in the channel was celebrated by “seven discharges of a field piece and three cheers.”

The super structure was two spans supported by rounded arches, braced and keyed. The work was finished November 21st amid great local rejoicing, and a corresponding degree of depression at the Hook.

Its cost had been $27,000. It was the first bridge across the Kennebec and the largest in the district of Maine.

—–

This bridge was never a profitable investment to its builders, who received no dividend on their stock for the first eight years.

It stood until Sunday, June 23, 1816, in the afternoon, when the eastern span fell from weakness and decay.

Mr. Lewis B. Hamlen, now living, saw it fall. After a delay of two years (during which time the ferry was restored) a second bridge was built (in 1818), after the model of the old one, but more elaborate, on the same spot, under contract, by Benjamin Brown and Ephraim Ballard, jun., for about $10,000.

This second bridge was destroyed by fire on the night of April 2, 1827.

Its successor was built under the superintendence of the same Ephraim Ballard during the following summer, and by the 18th of August was open for public travel.

This third bridge was bought by the city of Augusta in 1867 and made free to the public. It stood until 1890, when it was torn down and replaced by the present iron bridge at a cost of §59,000.

It may be well to preserve permanently in these pages the rates of toll as posted at the entrance of the three old toll-bridges:

Rates of Toll.

Each foot passenger, 2 cents.

Each horse and one rider, 12 cents.

Each single horse cart, sled or sleigh, 16 cents.

Each wheelbarrow, handcart, and every other vehicle capable of carrying a like weight, 4 cents.

Each team, including cart, sled or sleigh drawn by two beasts, 25 cents.

Each additional beast, 5 cents.

Each single horse and chaise, chair or sulkey, 20 cents.

Each coach, chariot, phaeton or curricle, 35 cents.

Neat cattle, exclusive of those rode on, in carriages, or in teams, each, 4 cents.

Sheep and swine, 4 cents.

The foregoing rates were painted black upon a white sign board 4×5 feet in size, in well proportioned letters two inches in perpendicular height.

—–

A few public spirited men had courageously burdened themselves for its erection, but thereby they had given their village an immense advantage in its lively race with its gallant neighbor.

The location of the Kennebec bridge at the Fort instead of at the Hook was intensely disappointing to the people of the latter place, who had long looked at their sister village with increasing jealousy.

The two sections of the town were now become hopelessly estranged and ill-feeling began to disturb the smooth running of town business.

Each village manifested a readiness to oppose the other in its pet schemes, whether they concerned public improvements or the election of candidates to office.

From this state of affairs there seemed to be no relief save by a division of the town.

The sentiment of Fort Western was favorable toward division; that of the Hook was therefore opposed.

The original movers for a division were Joseph North, Matthew Hayward, Stutely Springer, James Burton, James Bridge, Elias Craig, Gershom North, Theophilus Hamlen, John Springer and George Crosby — all of the Fort village.

The friends of division were numerous enough at a town meeting held in May, 1796, to appoint Daniel Cony “agent to prefer the petition to the general court during its then session.” The petition was presented by the town’s agent. Amos Stoddard, of the Hook, was then the town’s representative, and though himself originally opposed to division, he did not seek to defeat the proposition.

The desired act was passed by the legislature on the 20th of February, 1797, incorporating the Middle and North parishes into a town by the name of Harrington. Thus “after twenty-six years of united struggles, trials and labors, the town of Hallowell was divided.”*

The name chosen for the new town was in honor of a favorite courtier and honored minister of George the Second, Lord Harrington.

The once royally commissioned Colonel Dunbar had bestowed the same name sixty-eight years before to ancient Pemaquid (the present town of Bristol), but at the end of his brief though brilliant administration in Maine, Massachusetts prejudice discarded the name, with others equally eminent (Townsend and Walpole), which he had given to the towns of his founding.

The limits of the new town of Harrington embraced nearly two-thirds of the territory of old Hallowell. Its number of acres was 36,011. It retained about one-half of the valuation and population. It contained 250 polls, 119 houses, 84 barns, 21 shops, 74 horses, 157 oxen, 307 cows and three-years old cattle, 219 younger cattle, 620 tons of shipping, 7 saw mills and grist mills, $6,870 worth of stock in trade, and $3,000 at interest. One year later the population was 1,140.

=====

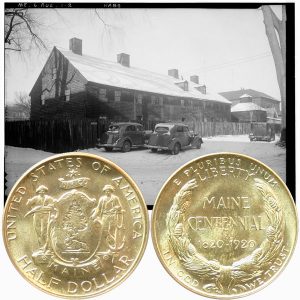

The Maine Commemorative Silver Half Dollar Coin shows with an image of Fort Western, circa 1930s.