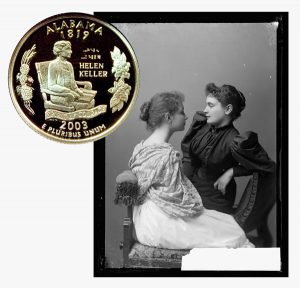

Today, the Alabama State Quarter Coin with its design of Helen Keller remembers the day Anne Sullivan arrived to begin teaching the young blind and deaf girl.

In the Library of Southern Literature, published in 1907, D. S. Burleson wrote an article about the life, struggles and accomplishments of the young girl:

=====

Helen Adams Keller was born June 27, 1880, in Tuscumbia, Alabama.

On her father’s side she is the great-granddaughter of Alexander Moore, an aide of La Fayette’s, and a great- great-granddaughter of Alexander Spotswood, an early colonial governor of Virginia; she is also a fourth cousin of General Robert E. Lee.

On her mother’s side she is related to the celebrated Adams and Everett families of Massachusetts. Her maternal grandfather, Charles Adams, was a brigadier-general in the Confederate Army, while her father, Arthur H. Keller, was a captain.

The latter for many years was editor of the Northern Alabamian, a weekly newspaper published in Tuscumbia.

Captain Keller was a man of liberal culture and unbounded hospitality; kindly, generous, and chivalrous — a true representative of the old school of Southern gentlemen.

At the age of nineteen months, Miss Keller, through the effects of acute congestion of the stomach and brain, was left totally and permanently deaf and blind.

From this time till almost seven years of age she lived a long night of almost total darkness and silence. She refers to this period as a dream throughout and says that her only consciousness of it is merely tactual.

“As near as I can tell,” says she, “asleep or awake, I felt only with my body. I can recollect no process which I should now dignify with the term thought.”

As she grew older, however, and the necessity for expression became more and more urgent, she was often rebellious and gave way to frequent outbursts of passion.

” ‘Light! give me light!’ ” says she, ”was the wordless cry of my soul, and the light of love shone on me in that very hour.”

She here refers to the coming of her teacher, Miss Anne Mansfield Sullivan (now Mrs. John Albert Macy).

Acting on the advice of Dr. Alexander Graham Bell, Captain Keller had applied for a teacher to the Perkins Institution for the Blind, and in response three months later Miss Sullivan arrived in Tuscumbia, on March 3, 1887, to enter upon a work that has brought both teacher and pupil into international prominence.

Miss Sullivan had not been with her pupil more than a month, when perhaps the most significant event in the life of Miss Keller occurred.

On the fifth of April, Miss Sullivan writes: “She has learned that everything has a name . . . We went out to the pump-house and I made Helen hold her mug under the spout while I pumped. As the cold water gushed forth, filling the mug, I spelled ‘w-a-t-e-r’ in Helen’s free hand. The word coming so close upon the sensation of cold water rushing over her hand seemed to startle her. She dropped her mug and stood as one transfixed. A new light came into her face.”

This light Miss Keller refers to as marking the awakening of her soul. To quote her own words:

“Suddenly I felt the misty consciousness of something forgotten — a thrill of returning thought; and somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew that ‘w-a-t-e-r’ meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. That living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, set it free!”

Thereupon Miss Keller’s education went forward with astonishing rapidity. On the seventeenth of June, about three and a half months after the first word was spelled into her hand, she wrote her first letter.

By the eighteenth of September, she knew six hundred words. By October she was telling stories in which the imagination played an important part.

In November, she wrote Dr. Alexander Bell a letter of one hundred and forty-five words, marking her sentences correctly, with capitals and periods.

In the spring of 1890 Miss Keller learned to speak. Miss Sarah Fuller, principal of the Horace Mann School, gave her eleven lessons in all.

The method was to have Miss Keller move her hand lightly over Miss Fuller’s face and feel the position of her tongue and lips when she made a sound. In an hour Miss Keller had learned six sounds.

“I shall never forget the surprise and delight I felt,” says she, “when I uttered my first connected sentence — ‘It is warm.’ ”

In 1892, at the age of twelve, Miss Keller wrote a sketch of her life for The Youth’s Companion. Her style in this was excellent for one of her youth, and promised much that has been fulfilled in her later writings.

Before October, 1893, she had read the histories of Greece, Rome, and the United States, knew a little French, and had begun the study of Latin.

In 1894 she entered the Wright-Humason School for the Deaf in New York City, chiefly for the purpose of vocal culture and training in lip reading, but also studied arithmetic, physical geography, French and German. Here she remained for two years.

In the fall of 1896 she entered the Cambridge School for Young Ladies to be prepared for Radcliffe, for, says she, “A potent force within me, stronger than the persuasion of my friends, stronger even than the pleadings of my heart, had impelled me to try my strength by the standards of those who see and hear.”

She continued in the Cambridge School for a little over one session; was then withdrawn and placed under the instruction of Mr. Merton S. Keith of Cambridge until she took her examinations in June, 1899, to enter Radcliffe.

These, despite many perplexing difficulties, she passed successfully, with credit in Advanced Latin.

In the fall of 1900 Miss Keller entered Radcliffe. During her four years there she had many disadvantages to labor against. She was practically alone in the presence of her instructors, getting only so much of their lectures as could be spelled into her hand, and could take no notes, as her hand was occupied.

She had to write her exercises on a typewriter so that her professors, who knew nothing of Braille, could read them.

Most of her text-books had to be spelled to her, since very few of those she needed were in raised print.

In 1904 Miss Keller took her degree at Radcliffe.

During this same year she was honored with a special day, known as ” Helen Keller Day,” at the St. Louis Exposition, on which occasion she was present and made an address.

A part of the following winter she spent at the home of her mother in Florence, Alabama.

Since that time she has been living at Wrentham, Massachusetts, with her former teacher, Mrs. John A. Macy.

Here, so she tells us in her article in the Ladies’ Home Journal, September, 1905, “What I am Doing,” she leads a very busy life; attending to her little domestic duties, answering letters, preparing addresses, writing articles, for Miss Keller is an occasional contributor to a number of leading periodicals, such as The Century, The Ladies’ Home Journal, The World’s Work, Current Literature, Charities, and others.

She has also found time to get out another volume entitled ‘The World I Live In,’ which appeared in 1908.

Such are some of the facts in the life of Miss Keller.

…

=====

The Alabama State Quarter Coin shows with an image of Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan, circa 1890s.