Today, the Bicentennial Half Dollar Coin goes back in time to view a satirical commentary on the issue of tea versus liberty 241 years ago.

The New England Magazine, Volume 30 from 1904 included an article about Newspaper Satire During the American Revolution by Frederic Austin Ogg.

The piece began:

=====

One has but to glance over the dingy files of the “New York Packet” or the “Pennsylvania Journal,” now preserved in some of our larger libraries, to be vividly impressed with the contrast between the newspapers of a century and a quarter ago and those of today.

Even the most aspiring of the former were small, poorly printed sheets, barren, for the most part, of illustrations, and altogether lacking in numerous desirable qualities now to be found in the commonest product of journalistic enterprise.

Yet in proportion to their number and the facilities which existed for their circulation, the newspapers of the Revolutionary era constituted no less important an influence in the life of the people than do those of our own time.

They were not merely newspapers. They partook largely of the nature of controversial brochures and became the clearing-houses of the literary-minded.

They were utilized to the utmost by the lawyer, the physician, the scholar, the poet, and most of all by the politician.

In the year 1768 the number of newspapers published in America was twenty-five, to which several were added before the close of the Revolutionary period.

As the breach with the mother country widened these newspapers became the storm-centers of the controversy.

Until 1775 one finds comparatively little satire—of a political nature, at least—in the volume of colonial literature. But after the actual outbreak of the war such literature grows voluminous.

The specimens which follow are not chosen to represent any particular type but rather the range and qualities of the satire which filled the newspapers of the Revolution and which had so much to do, on the one hand with sustaining, on the other with impeding, that movement.

It was on Tuesday, December 16, 1773, that a party of fifty New Englanders disguised as Mohawk Indians put to a practical test in Boston harbor the vexed question as to how “tea would mingle with saltwater.”

Of course the episode created no little astonishment and aroused a vigorous discussion in governmental circles in England.

“To repeal the tea-duty now would stamp us with timidity,” declared Lord North, the Prime Minister; and the dominant political party quite agreed.

Following this line of argument, it was determined, though against much protest, that the tea-duty should remain.

Tea, in other words, was to be made the exclusive instrument of maintaining the avowed parliamentary right to tax the colonists.

This decision determined the direction in which the spirit of resistance in America should find its chief expression.

Obviously the British designs might best be thwarted and the authors of them most discomfited by a general refusal throughout the colonies to use tea in any quantity or under any conditions until the odious tax should be removed.

Numerous resolutions and considerable legislative enactments were accordingly passed to this effect.

But there were some whose patriotism could not be stretched quite so far as to deny themselves their favorite beverage—particularly in the face of the following somewhat urgent invitation which went the round of the British and Tory newspapers:

“O Boston wives and maids, draw near and see Our delicate Souchong and Hyson tea, Buy it, my charming girls, fair, black, or brown, If not, we’ll cut your throats and burn your town.”

The following, communicated by “E. B.,” is taken from the “Pennsylvania Journal” of March 1, I775, and is, of course, directed against the considerable number of people who, as a contemporary put it, placed “Hyson-tea” before “Liber-tea”:

“The following petition came to my hand by accident; whether it is to be presented to the Assembly now sitting at Philadelphia, the next Congress or Committee, I cannot say. But it is certainly going forward and must convince every thinking person that the measures of the late Congress were very weak, wicked, and foolish, and that the opposition to them is much more considerable and respectable than perhaps many have imagined:

“The Petition of divers OLD WOMEN of the city of Philadelphia: humbly sheweth:—That your petitioners, as well spinsters as married, having been long accustomed to the drinking of tea, fear it will be utterly impossible for them to exhibit so much patriotism as wholly to disuse it.

“Your petitioners beg leave to observe that, having already done all possible injury to their nerves and health with this delectable herb, they shall think it extremely hard not to enjoy it for the remainder of their lives.

“Your petitioners would further represent, that coffee and chocolate, or any other substitute hitherto proposed, they humbly apprehend from their heaviness, must destroy that brilliancy of fancy, and fluency of expression, usually found at tea tables, when they are handling the conduct or character of their absent acquaintances.

“Your petitioners are also informed that there are several other old women of the other sex, laboring under the like difficulties, who apprehend the above restriction will be wholly unsupportable; and that it is a sacrifice infinitely too great to be made to save the lives, liberties, and privileges of any country whatever.

“Your petitioners, therefore, humbly pray the premises may be taken into serious consideration, and that they may be excepted from the resolution adopted by the late Congress, where in your petitioners conceive they were not represented; more especially as your petitioners only pray for an indulgence to those spinsters, whom age or ugliness have rendered desperate in the expectation of husbands; those of the married, where infirmities and ill-behavior have made their husbands long since tired of them, and those old women of the male gender who will most naturally be found in such company.

“And your petitioners as in duty bound shall ever pray, &c.”

Throughout the Revolution the issuing of a British proclamation was always the signal for the sharp wits from one end of the country to the other.

The orders caused to be published successively by Dunmore, Howe, Clinton, Cornwallis, and others of lesser note, were parodied and satirized until the originals had been made public laughing-stocks.

It would not be an easy matter to estimate the influence which these parodies and satires had throughout the colonies in nerving the people to reject with scorn the offers of conciliation held out by the enemy.

…

=====

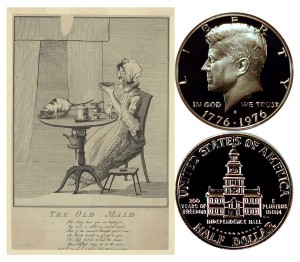

The Bicentennial Half Dollar Coin shows beside an artist’s image of an elderly woman drinking tea, circa 1775.