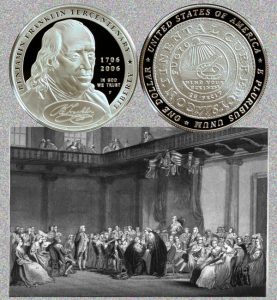

Today, the Benjamin Franklin Founding Father Commemorative Silver Dollar Coin remembers when a lawyer’s diatribe and accusations helped spur a revolution on January 29, 1774.

From the Life of Benjamin Franklin, published in London, 1826:

=====

Hopes were at this period entertained in both countries, of an adjustment of the differences between the colonies and Great Britain; and Dr Franklin had some thoughts of returning to America in 1773, to aid in this good work; but an affair of a most singular description suddenly involved him personally with the government, and exasperated the public mind, in Massachusetts in particular, to the utmost degree.

This province considered itself more deeply aggrieved by the stationing of a permanent military force there, with the avowed design of enforcing submission.

As early as March 1770, a quarrel had taken place between the towns-people, and the soldiers, in which several of the former were kilted. This event was commemorated for two or three years with great solemnity, when the ablest popular leaders harangued them on the horrors of slavery and arbitrary power.

In the course of this period the judges of the province, to preserve them in the interest of the mother- country, were made independent of the people, and paid entirely by the crown.

This the assembly, who had hitherto voted them an annual income, resented as a kind of bribery, and in 1772 impeached chief-justice Oliver as receiving corrupt and illegal fees.

Governor Bernard could find no mode of defeating this measure, but the dissolving the assembly.

In this province the popular leaders had not the discretion and good-humor of Franklin, but personal animosities exasperated the public discontents, and the lieutenant-governor, judge Oliver, and others, wrote to the secretary of state at home, pressing the necessity of coercion, and giving distorted pictures of public affairs.

The letters of these parties were brought to Dr Franklin, to convince him, as he says, that while he was blaming the ministry at home, their measures in fact were instigated and called for by a strong party in the colonies.

It is proper to notice here, that Dr Franklin has been accused of obtaining those letters surreptitiously, through his office of postmaster-general for America.

No proof however of any unfair mode of obtaining them was ever exhibited at the time.

He only, as he states, had the originals deposited with him, under the seal of secrecy as to the channel through which they were obtained, and which therefore he never would disclose.

As the agent for Massachusetts Bay, he applied for leave to transmit those letters to his constituents, which was given to him, as he states, on the condition that they should not be printed or copied, that they should only be shown to a few of the principal persons at Boston, and that they should be carefully sent back.

Upon these conditions he transmitted them to America.

Of these famous letters nothing more is now known, than that they were addressed to Mr. Thomas Whately, secretary to the treasury.

No copies of them have appeared among the writings or papers of Franklin, but from the indignant strain in which he speaks of them, as the production of “time- servers” seeking their own private emolument through any quantity of public mischief; betrayers of the interests, not of their native country only, but of the government they pretended to serve, &c., they were no- doubt highly insidious and inflammatory.

At Boston the public anger and animosity excited by them was almost without bounds.

The assembly drew up a petition and remonstrance to his majesty, in which they prayed for justice against the governor and lieutenant-governor, as betrayers of the public trust and of the people they governed, and as sending home private, partial, and false information concerning them.

A day being fixed for hearing this petition and remonstrance before the privy council, Dr Franklin attended at that board, as the agent of Massachusetts Bay, and Mr. Weddeburne then attorney-general, as -counsel for the governor and lieutenant-governor.

Finding the business thus warmly espoused by his majesty’s government, Dr Franklin applied for counsel and for time. Three weeks were allowed him, and the business was finally and fully argued on the 29th of January, 1774, when Mr. Dunning (afterwards Lord Ashburton) and Mr. J. Lee appeared with him as counsel on behalf of the Massachusetts Assembly.

The speeches of the accusing counsel were never reported, but the extracts which Mr. Dunning read from these famous letters, will sufficiently substantiate Dr Franklin’s character of them.

Oliver suggested to the minister “to stipulate with the merchants of England, and purchase from them large quantities of goods proper for the American market; agreeing beforehand to allow them a premium equal to the advance of their stock, if the price of their goods were not enhanced by a twofold demand in future, even though the goods might lie on hand till this temporary stagnation of business ceased. By such a step,” said he, “the game will be up with my countrymen.”

On another occasion he says, “that some method should be devised to take off the original incendiaries, whose writings supplied the fuel of sedition through the Boston Gazette.”

Mr. Hutchinson declared there must be an abridgment of English liberties in the colonies, or the government could not proceed.

Mr. Wedderburne directed the whole force of his reply, not to the contents of the letters, but to the manner of their having been obtained by Dr Franklin, which he contended could not have been “by fair means.”

“The writers did not give them to him,” said he, “nor yet did the deceased correspondent, who, from our intimacy, would otherwise have told me of it; nothing then will acquit Dr. Franklin of the charge of obtaining them by fraudulent or corrupt means, for the most malignant of purposes, unless he stole them from the person who stole them. This argument is irrefragable.”

“I hope, my lords,” he continued, “you will mark and brand the man, for the honor of this country, of Europe, and of mankind. Private correspondence has hitherto been held sacred in times of the greatest party rage, not only in politics, but in religion.”

“He has forfeited all the respect of societies and of men. Into what companies will he hereafter go with an unembarrassed face, or the honest intrepidity of virtue? Men will watch him with a jealous eye, they will hide their papers from him, and lock up their escrutoires. He will henceforth esteem it a libel to be called a man of letters, homo Trium literarum!

“But he not only took away the letters from one brother, but kept himself concealed till he nearly occasioned the murder of the other. It is impossible to read his account, expressive of the coolest and most deliberate malice, without horror. (Here he read a letter of Dr Franklin to the Public Advertiser.) Amidst those tragical events; of one person nearly murdered; of another answerable for the issue; of a worthy governor hurt in his dearest interests; the fate of America is in suspense: here is a man, who, with the utmost insensibility of remorse, stands up and avows himself the author of all. — I can compare it only to Zanga in Dr Young’s Revenge.

‘Know then ’twas I—

I forged the letter, —I disposed the picture:—

I hated, — I despised,— and I destroy.’

“I ask, my lords, whether the revengeful temper, attributed by poetic fiction only to the bloody African, is not surpassed by the coolness and apathy of the wily American.”

Franklin is said to have stood during the time of the delivery of this long speech at the council-table, immovably erect, and with not a feature disturbed by the attack.

The council, February 7th, voted the petition of the Massachusetts Assembly “groundless, vexatious, and scandalous,” and Dr. Franklin within a few days was dismissed from his office of postmaster-general.

The next morning Franklin told Dr Priestley he had never before been so sensible of the power of a good conscience; for that if he had not considered the thing for which he had been so much insulted as one of the best actions of his life, and what he should certainly do again in the same circumstances, he could not have supported it.

It is remarkable however that Dr. Franklin retained to a very late period a lively recollection of this insult.

He wore on this occasion a full dress suit of spotted Manchester velvet, and it is observed by Dr. Bancroft, that he had on the same dress when he signed the treaties of commerce and alliance with France; which led him to suspect, that he was influenced in that transaction by the remembrance of his former treatment before the council.

=====

The Benjamin Franklin Founding Father Commemorative Silver Dollar Coin shows with an artist’s portrayal of the privy council of January 29, 1774.