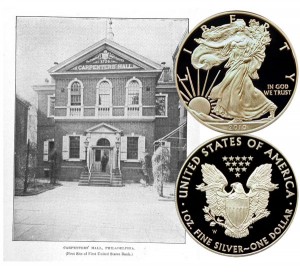

Today, a modern American Silver Eagle Dollar Coin remembers the early days of banking when the First Bank of the United States opened its doors on December 12, 1791.

Though not the first bank, earlier banks provided localized services.

This bank was approved for the national level with part of its objectives to foster a greater union among the states.

A summary in Triumphs and Wonders of the 19th Century by James Penny Boyd, published in 1899 provided historical highlights:

=====

EARLY BANKING IN THE UNITED STATES.

The first banks in the United States owed their origin to Robert Morris and Alexander Hamilton.

Morris, as early as 1763, conceived the plan of a bank to assist in developing American trade, and in 1779, Hamilton proposed the organization of “The Company of the Bank of the United States.”

These plans did not mature, but were followed, at the suggestion of Thomas Paine, by an association of ninety-two subscribers to a fund of 300,000 pounds Pennsylvania currency to support the Revolutionary army.

This association became known as the Pennsylvania Bank.

It commenced business July 17, 1780, and after a career of a year and a half, during which time it greatly aided the government in furnishing army supplies, its affairs were wound up.

On May 17, 1781, Hamilton presented the plan of a bank to Congress, which was to be truly national, and “created avowedly to aid the United States.”

Its name was to be the Bank of North America, with a subscription of $400,000 in gold and silver, and its notes, payable on demand, to be receivable for duties and taxes in every State.

Congress approved the plan, and Morris, then Superintendent of Finance, published it, with an address showing its advantages to the government and people, then suffering from the ill effects of a depreciated currency.

The Bank of North America was organized November 1, 1781, and began business January 7, 1782.

It creditably fulfilled its mission “to aid the United States,” and, after the expiration of its charter, became a State institution. In 1864 it entered the national banking system, though retaining its old name.

This bank was followed by the Rank of New York, which began business June 9. 1784, and by the Massachusetts Bank, which began business July 5, 1784.

FIRST UNITED STATES BANK. — This institution grew out of the recommendations of Alexander Hamilton, and formed a part of his scheme of strengthening the public credit and bringing about a closer union of States.

His plan was incorporated into a bill which passed the Senate January 3, 1791, and the House, January 20, 1791.

Washington signed it February 25, 1791.

The bill was hotly opposed as unconstitutional by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, Attorney-General Edmund Randolph, and in general by representatives from the Southern States.

The capital of the bank was fixed at $10,000,000, one fifth of which was to be subscribed by the government. The remainder was subscribed by individuals, and two hours after the opening of the books the capital was oversubscribed to the amount of 4000 shares.

The central bank was located at Philadelphia, and afterwards branches were established in New York. Boston, Baltimore, Washington, Norfolk, Charleston. Savannah, and New Orleans.

Business was first opened in Carpenters’ Hall, Philadelphia, December 12, 1791.

In July, 1797, the site was removed to a new building on Third Street, below Chestnut, and it remained there till the dissolution of the bank, with the exception of a brief removal to Germantown in 1798, during the epidemic of yellow fever.

Though this bank proved a profitable enterprise for the government, it failed to secure a renewal of its charter in 1811, chiefly because so many of its shares had passed into foreign hands.

=====

The periodical “Sound Currency,” published April 1, 1897, included more details about the First United States Bank along with its rules of charter:

=====

The Bank Established.

The Charter Secured.

Congress passed the act granting a charter to the Bank of the United States practically as proposed by Hamilton. This was not done, however, without strong opposition in Congress and elsewhere—based in part upon a denial of the utility of banks or upon special provisions in the pending bill, but mainly upon the unconstitutionality of such an act.

Their argument was that since there was in the Constitution no express grant of such a power to Congress, it must be considered as having been reserved to the States or to the people. In general the opposition came from the Republicans (as the present Democratic Party was then named).

In the House of Representatives the vote was 39 in favor to 19 against the measure. The nineteen who voted against the measure (including among their number James Madison) were, with one exception, from the States of Maryland, Virginia and North and South Carolina; while all but four of the 39 advocates were representatives of the Northern States.

Before signing the bill Washington called for the opinions of the members of his Cabinet. Edmund Randolph, Attorney-General, and Thomas Jefferson, Secretary of State, argued adversely to the power of Congress to charter a national bank.

Hamilton, Secretary of the Treasury, and Knox, Secretary of War, favored it—the former in a carefully prepared argument on the question of constitutionality supplementing his earlier report.

Washington signed the act, which thus became a law on February 25, 1791.

CONDITIONS OF THE CHARTER.

1. Capital. The capital was fixed at $10,000,000, divided into 25,000 shares of $400 each. One-fifth, $2,000,000, was to be subscribed by the Government on the terms noted below. The remaining $8,000,000 was open to subscription by the public, one-fourth to be paid in specie and three-fourths in Government obligations bearing 6 percent interest.

2. Administration. The protection of the small investors in the stock was secured by a graduated scale of voting which allowed each shareholder to cast one vote for one share, one additional vote for every additional two shares up to ten, another for every three shares, etc., no one being allowed to cast more than 30 votes. Foreign stockholders were not allowed to vote by proxy. The management was entrusted to a board of 25 directors—to serve without compensation— all of whom must be citizens of the United States. Not more than three-fourths were to be eligible for re-election—a provision urged by Hamilton in the belief that the rotation in office thus assured would be conducive to better and safer management.

3. The Government’s Interest. The President was authorized to subscribe for $2,000,000 of the stock. This, however, was to be, as Hamilton described the operation, merely “borrowing with one hand what is lent with the other;” as it was further provided that the money with which to pay for the stock was to be borrowed, from the bank, payable in ten annual installments of $200,000 each, or sooner if the Government should think fit. No other loans exceeding $100,000 were to be made to the Government without authority of law.

4. Note Issue. As in other banks chartered about this time, no express authority to issue notes to circulate as currency was conferred, as it was assumed that such a right existed unless especially prohibited. The issue of notes is several times referred to, however. It is provided, for example, that they shall be binding though not under seal; they are mentioned among the liabilities to be reported by the bank, and there is the provision “that the bills or notes of the said corporation originally made payable, or which shall have become payable, on demand, in gold or silver coin, shall be receivable in all payments to the United States.”

There was, however, a limit upon note issues in the section which limited all debts other than deposits to the amount of the capital stock, $10,000,000. In case of issues of notes in excess of this the directors were to be personally liable to creditors of the bank; but such of the directors as may have been absent or dissenting from the action might exonerate themselves by prompt notice of the fact of their absence or dissent to the President of the United States and to the stockholders, at a meeting called for that purpose.

5. Branches. The Directors were given authority to establish branches wherever, within the United States, they might deem proper.

6. Reports. The bank was required to furnish the Secretary of the Treasury as often as he should require, not exceeding once a week, a detailed statement of its financial condition, and the Secretary was given the right to inspect such general accounts on the books of the bank as referred to such statements.

7. Other Limitations. The bank was not forbidden to loan on real estate security, but could not hold real estate, beyond that necessary for its banking houses, unless it came into its hands in satisfaction of mortgage or judgments. The Government was pledged to grant no other bank charter during the continuance of this one, which was to run for twenty years.

THE BANK IN OPERATION.

In two hours after the Opening of the books the capital was over-subscribed to the amount of four thousand shares, and the corporation started off as a financial success. Oliver Wolcott, afterward Secretary of the Treasury, was offered the Presidency, but declined, and Thomas Willing, of Philadelphia, was selected.

The central bank was stationed at Philadelphia, beside the seat of Government, and $4,700,000 of the capital was reserved for that office. The remainder was distributed among the branches—of which eight were eventually established —at New York, Boston, Baltimore, Washington, Norfolk, Charleston, Savannah and New Orleans.

=====

The American Silver Eagle Dollar Coin shows with an image of Carpenters’ Hall, the initial location of the First Bank of the United States.