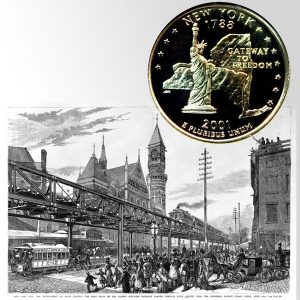

Today, the New York State Quarter Coin remembers when the Gilbert Elevated Railway opened on June 5, 1878 between Rector street and Central Park.

From the Railroad Gazette of September 16, 1904:

=====

Early Transportation in New York. By Henry E. Armstrong.

Between 1682, when Gov. Stuyvesant died on his farm, “the Great Bouwerie,” and the Revolution, the growth of New York was slow for a city of its destiny.

There was an average increase of population of only 150 a year.

In 1774 a census taken by the authorities showed a total of 22,861 souls.

Not until after the War of Independence do we find passenger transportation on a commercial basis.

In 1783 the rate for a carriage ride from the Battery to Murray Hill was fourteen shillings—about two dollars and a half.

For two shillings more the traveler could reach Gracie’s Point, opposite Hell Gate. For the same amount, 16 shillings, he might go up to Apthorpe’s, on the west side of the island, about where Ninety-second street is now.

The journey to Harlem was a day’s excursion and cost 38 shillings. When the Subway is open for traffic the New Yorker of 1904 will be able to go to Kingsbridge in half an hour for five cents.

The first serious effort to furnish transportation in New York was the stage line which was put on between Bowling Green and Bleecker street in 1830.

Competition soon became brisk. Coaches in all the glory of high colors, and embellished with portraits of celebrities, traversed the city from river to river, and from the point of the island, where the Aquarium (formerly Castle Clinton) stands today, to Greenwich Village and Yorkville.

The most pretentious stages were drawn by four horses and bore such honored names as Lady Washington, George Washington, and De Witt Clinton.

New York still boasts a line of buses on Fifth avenue, and the sight of them in an age of electric traction carries the mind back to a day when the Post Road to Boston ran through Madison Square, and what is now Central Park was sacred soil, wantonly wild and famous for the revolutionary relic of McGowan’s Pass.

Seven years before Madison Square was laid out, or in 1831, a great stride was made in transportation by the introduction of the horse-railroad. In that year the New York & Harlem Railroad Company was organized.

The pioneer of all street cars, the John Mason, named for the founder of the Chemical Bank and the first president of the world’s first horse-railroad company, made its initial trip between Prince and Fourteenth street on Nov. 26, 1832.

It carried the Mayor and Common Council of the city and John Stephenson, the builder.

When the subway of the Rapid Transit Construction Company is opened to traffic the occasion will be a red-letter day in the history of urban transportation, but it will not arouse and interest the people of New York as did the passage of the first horse-car through the streets, in 1832.

After the Civil War, when the city began to spread north of Central Park, which had been laid out in 1856, it became evident that the horse car service was behind the times.

The Hudson River Railroad landed its passengers at Thirtieth street and Ninth avenue, it was true, and the New York & New Haven and the Harlem railroads had termini in the neighborhood of Madison and Fourth avenues and Twenty-sixth street, but to avoid accidents trains had run as slowly as the horse-cars.

Agitation for quicker transportation to the foot of the island resulted between 1868 and 1870 in the incorporation of two underground railroad companies. One of them built an experimental section beneath Broadway from Warren to Murray street.

The excavation was made by a shield forced ahead by hydraulic pressure. Into the tunnel was introduced a steel casing 8 ft. in diameter, which was to hold a car as the piston fits in the cylinder. By powerful fans the car was to be blown on its way. This novelty was known as the Beach pneumatic road.

A public exhibition was set for April 26, 1870, and 18 daring men crowded themselves into the car and were pushed majestically from Murray to Warren. The company boldly announced that it would build 100 cars and soon have them running from the Battery to Harlem.

But that hole in the ground was soon abandoned, and the ambitious scheme to shoot business New York to Harlem pneumatically came to nothing.

Then there was the Arcade Railway, a picturesque idea that was never put into effect. The tracks were to be laid in a long arcade over the sidewalk the length of Broadway; but property owners along the route vigorously objected, and the promoters, calculating that the expense of construction would be altogether too great for a dividend payer, withdrew the scheme.

A Viaduct rail road to run through private property and cross intervening streets on substantial bridges shared the same fate.

Another project, the Greenwich Street Elevated Railroad, begun in 1866, had better luck; but never were promoters more abused or their public-spirited prospectus more derided.

One is reminded of the famous protest of Admiral Sir Isaac Coffin when the application for a charter for the Liverpool & Manchester Railway was before the House of Commons.

“Was the House aware,” asked that fine old Tory, “of the smoke and the noise, the hiss and the whirl which locomotive engines, passing at the rate of 10 or 12 miles an hour, would occasion? Neither the cattle plowing in the fields, nor grazing in the meadows, would view them without dismay. Iron would be raised in price 100 per cent. or more probably, exhausted altogether. it would be the greatest nuisance, the most complete disturber of quiet and comfort in all parts of the kingdom that the ingenuity of man could invent.“

But the promoters triumphed in spite of the Manhattan Coffins of 1866.

A one-track road was built from Battery Place through Greenwich street, and on July 2, 1867, New York was invited to ride on an air-line operated by cables.

Although steam locomotives were soon substituted the first elevated railroad in New York had a hard time of it.

Damned uphill and down, the butt of newspaper wits, and neglected by the traveling public, it struggled along against contumely and ingratitude until the sheriff got it. That was in 1871.

The legislature was asked at the session of 1872 for two rapid transit charters.

Dr. Rufus H. Gilbert, the applicant for one of them, proposed to suspend a pneumatic tube from lofty arches, and very much on the principle of the Beach device cars were to be slid through it noiselessly.

The roaring and grinding and creaking of the Greenwich street elevated trains was the chief objection to them.

New York is not so sensitive to noise now.

A steam railroad built up at the sides to save the modesty of second-story tenants was substituted for the fantastic plan of Dr. Gilbert, and then there was a return to the elevated railroad on Greenwich street.

The legislature of 1875 tackled the irrepressible problem again, passing the Husted bill for the appointment of a commission to decide as to the necessity (!) of rapid transit in New York, and, if it existed, to propose desirable routes.

A commission of Joseph Seligman, Louis B. Brown, Cornelius H. Delamater, Jordan L. Mott, and Charles J. Canda, recommended on July 13, that elevated steam railroads be built upon Second, Third, Sixth and Ninth avenues, and invited the Gilbert Company and the New York Company, the latter at the time operating a none too robust elevated road on Greenwich street, to enter upon the work of construction.

Before the end of 1876 the New York Company (now the Ninth avenue line), although assailed on all sides by litigants with extravagant damage claims, had pushed its tracks up to Fifty-ninth street, and was advertising “40 through trains” a day.

Cyrus W. Field, the Atlantic cable magician, invaded the rapid transit field in 1877, and bought a controlling interest.

By June 5, 1878, the Sixth avenue road was in operation from Rector street to Central Park.

The West Side lines were consolidated under the name of the Metropolitan Elevated Railroad.

The Third avenue line was operated as far as Forty-second street on August 26.

It was 1880 before the Second Avenue reached Sixty seventh street, but by the end of that year the elevated roads on both sides of the city, later known as the Manhattan Railway Company, had been extended to Harlem.

Some years before this there had been another consolidation, and a public work was completed which accomplished great things for rapid transit.

That was the assembling of the downtown stations of the Hudson River, New York & New Haven, and Harlem companies at Forty-second street under the colossal dome (for 1871) of Cornelius Vanderbilt’s Grand Central terminus.

Four years later the railroad tracks were shut in or removed from the streets below the Harlem River by tunnel and stone viaduct, an engineering work which cost $6,000,000. Half the expense was borne by the city.

After the completion of the fundamental lines of the east side elevated roads, in 1879-1880, there was no progress of especial interest in New York rapid transit until the Broadway horse car line was equipped with a cable, in 1892, to serve only a scant six years before its removal and the substitution of the conduit system of electrical traction, in 1898.

But surface cars on the crowded streets could furnish rapid transit only in name, although materially aiding in handling the crowds, and the demand for fast time from the residence part of town to the business section was so great that before the Ninth avenue elevated road had been open a year, it was reported in the Railroad Gazette that people had to be “turned away” during the rush hours, from stations north of Warren street.

So far as real rapid transit is concerned, therefore. there is a gap of 24 years—from 1880 to 1904, in the provision of new facilities for getting from one end of Manhattan Island to the other.

=====

The New York State Quarter Coin shows with an artist’s image of the Gilbert Elevated Railroad, circa 1878.