Today, the Jamestown Commemorative Silver Dollar Coin remembers when the men and boys set sail from England headed for their adventure in Virginia 411 years ago.

From The United States by James Wilford Garner, Henry Cabot Lodge, and John Bach McMaster, published in 1913:

=====

After the failure of Raleigh no single individual was found to risk his fame and fortune in efforts at colonization, but the work was soon taken up by corporate companies.

The success attending the Muscovy and East India Companies, which had been founded to trade with Russia and India respectively, led a few venturesome merchants and traders to inquire if similar results could not be obtained by corporate action in America.

The conditions were indeed vastly different, but the venture was made and a charter secured from King James I. in 1606 for a company with two subdivisions, the London Company and the Plymouth Company, so called from the names of the towns which became the headquarters of the two companies respectively.

The first was granted permission to plant a colony anywhere on the coast of Virginia (the name applied to all the English claims in America at this time) between the thirty- fourth and thirty-eighth degrees of north latitude; the second was given the same privilege between the forty-first and forty-fifth, neither company to plant a colony within one hundred miles of a settlement already made by the other.

The announcement of a new colonial policy such as had not yet been introduced in America was contained in the clause which declared that the colonists and their posterity should enjoy all “liberties, franchises and immunities” as though they were abiding in the realm — that is, they were to enjoy the benefits of the common law equally with the inhabitants of England.

This declaration really deserves to be called an epoch in the history of colonization.

The government of the colony was to be nominally in the hands of two councils, one resident in England, the other in the colony; but as one was appointed directly, and the other indirectly, by the king, all power was virtually in his hands.

The council in America was to administer affairs according to instructions issued by the king, but any laws or ordinances which it might make were subject to repeal by the crown or by the home council.

The form of government thus provided was absurdly cumbrous and soon had to be abandoned.

The first instructions ordered that the land tenure should be the same as in England ; that trial by jury should be preserved, and the supremacy of the king and of the Church of England maintained.

The colony itself was to be started on a system of communism.

In the words of Doyle, it was to be a “vast joint-stock farm, or collection of farms, worked by servants who were to receive, in return for their labor, all their necessaries and a share in the proceeds of the undertaking.”

All trade was to be in the hands of a treasurer or cape merchant, and was to be public.

The patentees were given the right to exact a duty of two and a half per cent, from all English subjects, and five per cent, from all foreigners trading with the colony.

For twenty years the proceeds were to accrue to the company, after that to the crown.

Among the first councilors appointed by the king were Sir Ferdinando Gorges, Sir Edwin Sandys, Sir Thomas Smythe and Sir Francis Popham, all able and well-known men of their time.

These preliminaries being completed, preparations were made to send out the first colony to take possession of the company’s lands.

On December 19, 1606, three puny vessels, with an aggregate tonnage of not over one hundred and sixty tons, sailed from England on what was perhaps, for Englishmen at least, the most important voyage in its results since Columbus had sailed out of Palos with his three caravels more than a hundred years previous.

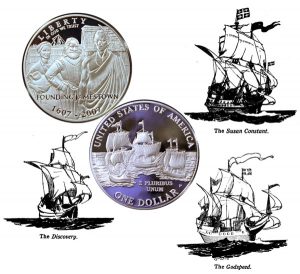

The three ships were called the Susan Constant, the Godspeed and the Discovery, all belonging to the Muscovy Company, and they carried one hundred and four settlers to the coast of Virginia under the command of Christopher Newport, a well-known seaman of the time.

The voyage was long and stormy and spring was well advanced when they entered Chesapeake Bay (May, 1607).

The two capes at the entrance of this bay were named Charles and Henry, in honor of the king’s sons, and one of the largest rivers flowing into the bay they called James, in honor of their king.

Sailing up this for fifty miles they selected a place for settlement and called it Jamestown.

An inventory of the settlers shows that they were ill-fitted for the task which they had undertaken.

Fifty-five, more than half the entire number, were ranked as “gentlemen,” that is, men disdaining labor, and out for adventure: a London tailor, a barber and a perfumer were sent along to look after the wants of these gentlemen.

Twelve laborers and a few artisans were expected to furnish the necessary brawn and sinew.

There was not a woman in the company.

The place selected for the town, a malarial peninsula, chosen in flat contradiction to the instructions of the Virginia council, was no better suited to colony-building than the men who settled there.

However, the company contained a few men of worth, among them John Smith, whose life, says Fiske, reads like a chapter from “The Cloister and the Hearth,” and but for whose presence and foresight the colony would have met the fate of Raleigh’s earlier experiment.

The thirst for gold was still strong, and the settlers were instructed to find this and also a way to India.

So that while others were engaged in erecting huts or stretching tents, Captains Newport and Smith went up the river on this quest, but after a conference with the Indian chief, Powhatan, the supreme ruler in these parts, turned back at the falls where Richmond now stands and returned to Jamestown.

Shortly thereafter Newport sailed for England with a batch of cheerful reports and a quantity of ore which proved to have been “taken from the wrong heap.”

It was hardly reasonable to expect that such a company would be harmonious.

Dissensions had broken out on shipboard, where Smith was kept in irons for a month mainly on account of jealousy, and was actually excluded from the council, of which he had been appointed a member, for another month after landing.

After the departure of Newport in July the dissensions increased and the troubles of the colonists grew apace.

To internal trouble was added the haunting fear of Indian attacks, for, in spite of special instructions to that end, some of the red men had not been well treated by the newcomers.

Heat, famine, and fever made deadly work, and by the end of September about half the colonists had succumbed.

Fortunately for the colonists Smith was among the survivors.

Several of his enemies had perished and this made it all the easier for him to gain the ascendency.

The story of his career for the next two years forms one of the most romantic pages in American history.

He has left us an account of a still more remarkable career preceding this in Europe and Asia Minor, so remarkable, indeed, that its credibility has been seriously doubted by careful critics.

There is no question that he was a vain fellow, a sort of “braggart captain;” but neither is there any doubt that he was a remarkable man, a true Elizabethan Englishman, and that there is a considerable element of truth in his narrative of his own exploits.

=====

The Jamestown Commemorative Silver Dollar Coin shows with artists’ images of the Susan Constant, Godspeed and Discovery.