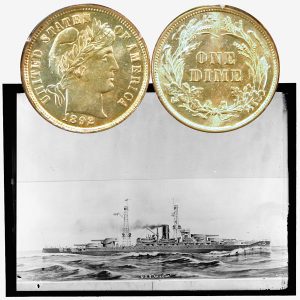

Today, the Liberty Head Silver Dime Coin remembers when the large crowd cheered the christening launch of the USS Arizona on June 19, 1915.

From the New York Tribune of the following day:

=====

Cheering Thousands at Navy Yard Watch Great Super Dreadnought Given to Sea—Wine Splashes Bows, But Water Bottle Refuses to Break.

Philosophers say that every you move even your little finger alter the center of gravity of world just that much. If that is so, then the sensitive center of gravity got one of the scares of its life yesterday at eleven minutes after 1 o’clock. At that moment 26,000,000 pounds of steel slid off the earth and tumbled into the East River.

The world’s center of gravity was not the only thing that was disturbed thereby. The world’s comparative naval statistics will also have to be adjusted, for those 26,000,000 pounds of steel made up the hull of the mightiest battle machine ever wrought the by the hands of mere men—the super dreadnought Arizona.

The Arizona does not belong to the grape juice navy. She belongs to the good old ships of the line christened with stuff with a sting in it. There were those who thought in the watery times of Josephus that she should be christened with nothing but water, especially since Arizona is dry state. There were others who held that a ship was not christened unless she went down the ways with the taste of champagne in her teeth.

Finally the controversy was compromised by placing in the hands of Miss Esther Ross, of Preston, Ariz., who stood sponsor for the ship, a magnum of champagne and a little bottle of water gathered at the brink of the Roosevelt Dam in Arizona.

But the great, grim fighter was no man to take a chaser with her liquor. She took the champagne between her teeth and swallowed it all, but she refused the water, and the bottle dangled unbroken at the end of its string, untasted and having no part in the ceremony.

At three minutes to 1 o’clock the first warning whistle came to the christening party that the great thing was about to happen. Naval Constructor John E. Otterson, who was using all his naval science in giving his undivided attention to Miss Ross, handed her the bottle of champagne, and instructed her again just how to break it.

Governor Hunt of Arizona pulled out the small bottle of water and gave that to Miss Ross also. Mr. Otterson did not lavish such minute instructions on that bottle. He was not interested in pure water from Roosevelt Dam.

Another warning whistle came, and from afar down in the depths below the hull there came a few blows of a sledge hammer. But there were only a few. All the unnecessary parts of her cradle had been knocked out earlier in the day. She was resting in a sliding cradle, weighing 500 tons, that was to go into the river with her.

The real work of starting that 13,500 ton mass was being done by the hand of Naval Constructor Stocker, who was releasing the great hydraulic trigger. For ten minutes the christening party in their little close-packed rostrum, built about the ship’s prow stood waiting.

Close beside Miss Ross and her mentor Otterson stood another man, with his ear to a telephone. Before the party was aware of it word came to him that all was clear.

Then the leviathan began to move. Unless you had the edge of the prow in line with some stationary object that first movement was imperceptible. There was a fraction of a second of this stealthy beginning before the crowd saw that the great hulk was going. It seemed almost inconceivable that such a mass could really move. But it did; there came a sudden quickening of her movement, and everyone saw that she was going.

A shout went up, and then Miss Ross smashed the christening stuff against the great wall of steel slipping away from her. There was a white, feathery spout of the champagne, and with rapidly increasing speed the Arizona went down the ways.

She was so immense with her 608 feet of length she seemed to move by inches when she travelled yards. There was no noise, no swaying, just a steady, irresistible movement of an unbelievably big mass of steel into the water. They say, the men of science who built her, that by the time the Arizona hit the water she was travelling at the rate of fifteen miles an hour, but it did not look possible.

The super dreadnought took the water as easily as a rowboat. A brimming glass on her deck would scarcely have spilled a drop, it seemed, she went so steadily into the water. Then as she was completely in, resting as high and buoyantly as a cork, there was a little dip of her prow, and she swam on serenely out into the river, in a great graceful curve, turning upstream. But not far, for, like a pack of terriers attacking a great boar, a score of tugs closed in about her and snubbed her up. She had displaced 31,400 tons, but only what looked like a little ripple ran over the water as she glided in.

The Arizona slid to the water over two parallel strips of planking 70 inches wide and 600 feet long, built of smoothed timbers nicely joined and strongly braced. The lower ends of these ways extended under water fur 160 feet eleven feet below the surface.

In the cradle and the sliding ways there were the equivalent of 350,000 board feet of lumber. The slope of the inclined plane was at the rate of eleven-sixteenths of an inch to the foot. Thirty thousand pounds of a specially mixed grease were put between the sliding ways of the launching cradle and the stationary ways. The elapsed time between the first move and the moment she floated clear was about thirty seconds, and at the end she was going twenty-two feet a second, or fifteen miles an hour.

Greater care had to be taken in launching that mountain of steel than in launching a birch bark canoe. Any little precaution overlooked would have meant to warp the hull and perhaps tear her asunder. Inside she was braced and shored in every direction with timbers to stiffen her against the various stresses and strains incident to her moving.

At her bows nine toggle blocks on each side were lashed together by steel wire ropes running under the keel. These pressed snugly on the outside against mighty shoring within, holding the forward part of the vessel solid so there would be no warping of her structure when the after part began to float and the bow was still on shore.

Within a hundred feet of the stern were dog shores, long blunt wedges that humped up under the cradle, holding the whole mass from moving. A sixty-ton hydraulic jack depressed the dog shores, and then the only thing that held the ship was the hydraulic triggers, a new device in launching.

They were under the midships section, two steel bars, one engaging the cradle each side of the keel. They were held in place by hydraulic piston rams in cylinders under a pressure of from 1,700 to 3,900 pounds to the square inch. Naval Constructor Stocker, who was in charge of the launching, stood with his hand on the levers controlling these triggers, and it was his arm that gave the final impulse which sent the great ship on her way.

He and his assistants were down beneath the hull, in the trigger pit. The great mass moved above them, then gained speed. If she looked as if she were moving slowly to the spectators above the ground, there was nothing slow about the way she was flying over their heads at the end —and then she was gone, and they stood blinking in the sun. They climbed out and watched the tugs in the river get her.

=====

The Liberty Head Silver Dime Coin shows with an image of the USS Arizona traveling in open water, circa 1915.