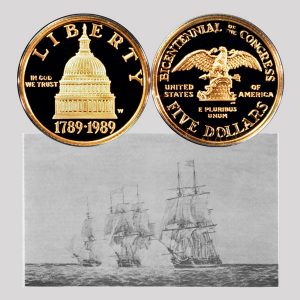

Today, the Congress Commemorative Gold Five-Dollar Coin remembers December 13, 1775 when the Continental Congress agreed to fund shipbuilding for their new navy formed earlier in October.

From The Navy of the American Revolution, Its Administration, Its Policy, and Its Achievements by Charles Oscar Paullin, published in 1906:

=====

When the Rhode Island instructions came up on October 7, a debate ensued, a synopsis of which has been left us by John Adams.

The discussion was participated in by Robert Treat Paine, Samuel Adams, and John Adams of Massachusetts, John Rutledge and Christopher Gadsden of South Carolina, Samuel Chase of Maryland, Stephen Hopkins of Rhode Island, Dr. John J. Zubly of Georgia, Eliphalet Dyer and Silas Deane of Connecticut, and Peyton Randolph of Virginia.

When the debate took place, the consideration of the Rhode Island instructions had been postponed until the 16th, and the motion before the Congress was to appoint a committee “to consider the whole subject.”

The establishing of a navy naturally found least favor among the members coming from the agricultural South, and most support from those of maritime New England.

Chase, of Maryland, declared, “It is the maddest idea in the world to think of building an American fleet; its latitude is wonderful; we should mortgage the whole continent.” He added, however: “We should provide, for gaining intelligence, two swift sailing vessels.”

Zubly, of Georgia, said: “If the plans of some gentlemen are to take place, an American fleet must be a part of it, extravagant as it is.”

Gadsden, of South Carolina, temperately favored the procuring of armed vessels, thinking that it was “absolutely necessary that some plan of defense, by sea, should be adopted.” He was opposed to the “extensiveness of the Rhode Island plan,” although he thought that it should be considered.

The friends of the navy acted on the defensive. They probably realized that their cause might well bide its time.

Its opponents, to use John Adams’s phrase, were “lightly skirmishing.”

In the end the motion was lost, and consideration of the instructions was deferred until the 16th.

On October 16, and again on November 16, the Rhode Island instructions were postponed.

Samuel Ward had hopes for a favorable action on the latter day. On November 16 he wrote from Philadelphia to his brother in Rhode Island:

“Our instruction for an American fleet has been long upon the table. When it was first presented, it was looked upon as perfectly chimerical; but gentlemen now consider it in a very different light. It is this day to be taken into consideration, and I have great hopes of carrying it. Dr. Franklin, Colonel Lee, the two Adamses, and many others, will support it. If it succeeds, I shall remember your ideas of our building two of the ships.”

The several postponements of the Rhode Island instructions make it clear that Congress was slow to reach the conclusion that the “building of a fleet” was desirable or feasible.

It was one thing to fit out a few small vessels for intercepting British transports, and quite another to build a fleet of frigates.

It is not surprising that under the circumstances Congress hesitated to embark on the larger undertaking.

The difference in the presentation to Congress of the two propositions, both of which involved the procuring of a naval armament, is worthy of note, for it had its influence on legislation.

The appointment of a committee to prepare a plan for intercepting transports, put the question in a softened, more veiled, and less direct form.

It pointed the wedge of naval legislation by a tactful presentation, and drove it home with an exigency.

In Chapter I the increase of sentiment in favor of a naval armament during the latter part of October and during November has been shown, and the important naval legislation of November has been presented.

It was now only a question of time until Congress would heed the recommendations of Rhode Island.

On December 9, 1775, the Rhode Island instructions once more came up, and a day for their consideration was fixed, Monday, December 11.

On the 11th, “agreeable to the order of the day, the Congress took into consideration the instructions given to the delegates of Rhode Island;” whereupon a committee of twelve was appointed to devise ways and means for furnishing these colonies with a naval armament.

This committee performed its work with commendable celerity, and brought in, on December 13, one of the most important reports in the history of the naval affairs under the Revolution, for by its acceptance Congress committed itself to the establishment of a considerable naval force.

Congress determined to build thirteen frigates, five of 32, five of 28, and three of 24 guns, to be distributed, as regards the place of their construction, among the states as follows: New Hampshire, one; Massachusetts, two; Rhode Island, two; Connecticut, one; New York, two; Pennsylvania, four; and Maryland, one.

It was estimated that these ships would cost on the average $66,666.67 each, and that their whole cost would amount to $866,666.67. All the materials for fitting them for sea could be procured in America except canvas and gunpowder.

On December 14 a committee consisting of one member from each colony was chosen by ballot to take charge of the building and fitting out of these vessels.

The members chosen with their states were as follows: Josiah Bartlett, New Hampshire; John Hancock, Massachusetts; Stephen Hopkins, Rhode Island; Silas Deane, Connecticut; Francis Lewis, New York; Stephen Crane, New Jersey; Robert Morris, Pennsylvania; George Read, Delaware; Samuel Chase, Maryland; R. H. Lee, Virginia; Joseph Hewes, North Carolina; Christopher Gadsden, South Carolina; John Houston, Georgia.

This committee was substantially the same as that which reported the naval increase on the 13th; the only changes were in the members from Massachusetts and Maryland, and in the addition of a member from Georgia.

The committee was a very able one, comprising several of the foremost men of the Revolution.

Hancock, Morris, Hopkins, and Hewes were especially interested in naval and maritime affairs.

The absence of the name of John Adams is probably accounted for by his return home early in December.

This new committee was soon designated as the Marine Committee, by which name it was referred to throughout the Revolution.

Larger, and, with its engrossing work of building and fitting out the thirteen frigates, more active than the Naval Committee, it soon overshadowed and finally absorbed its colleague.

This absorption was facilitated no doubt by the fact that the four members of the Naval Committee remaining in January, 1776, also belonged to the new committee.

With the exception of the rendering of its accounts, the duties of the Naval Committee came to an end with the sailing of Hopkins’s fleet in February, 1776.

The Marine Committee now acquired a firm grasp of the naval business of the colonies, and from this time until December, 1779, it was the recognized and responsible head of the Naval Department, and as such, during the period that saw the rise and partial decline of the Continental navy, its history is of prime importance.

=====

The first thirteen ships constructed for the continental navy were named:

Hancock, Raleigh, Randolph, Warren, and Washington for the five 32-gun ships,

Effingham, Montgomery, Providence, Trumble, and Virginia for the five 28-gun ships, and

Boston, Congress, and Delaware for the three 24-gun ships.

The Congress Commemorative Gold Five-Dollar Coin shows with an image of the Hancock and Boston continental navy ships capturing the British frigate Fox, circa 1777.