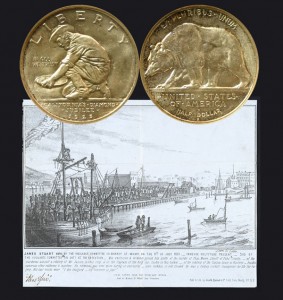

Today the California Diamond Jubilee Commemorative Silver Half Dollar Coin remembers the first organization of the Committee of Vigilance in San Francisco on June 9, 1851.

Excerpt from the Dearborn Independent of June 1922:

=====

Mysteries of California’s Vigilantes Is Cleared

Young Woman’s College Thesis First Comprehensive Compilation of Facts

Probably no two episodes in the history of the United States have been so beclouded by a fog of misinformation, as have the activities of the California Vigilantes of 1851 and 1856.

The impression is general that these bodies—the second having been a reorganization of the first, although for a different purpose—were composed of impetuous, hot headed, domineering men who went outside the law to enforce a law they had written for themselves.

They have been referred to as “mobs,” and accused of lynching, whipping and deporting innocent men, without form of trial.

Even historians, who have had at least some records of those thrilling days at their command, have considered the two “Committees of Vigilance” of San Francisco, as having done a greater wrong in taking the law into their own hands, than would have been done by the men they punished so summarily.

Now comes, however, an explorer in the realms of records, with the entire written report of every meeting of these Committees of Vigilance, presenting a complete account of every step taken by them, of every man arrested, tried, punished, warned or released, and revealing to Americans pages of American history never before shown to them.

The investigator, whose work has produced a valuable volume, is a woman— Miss Mary Floyd Williams, of Berkeley, California, the daughter of Edwards C. Williams who came to San Francisco as a first lieutenant in the famous First Regiment, New York Volunteers, under Colonel J. D. Stevenson, in March, 1847, and afterward became an active member in the first organization of Vigilantes in 1851.

By their own records, Miss Williams proves that the Vigilantes, instead of being mobs, were most carefully organized, composed of the leading men of San Francisco, whose deliberations over even minor cases often occupied days and nights before decision as to punishment or release, or even arrest of a suspect, was reached.

They kept detailed accounts in writing of every meeting, of every debate and of the speeches made in those debates, and, thereafter, of every action and why it was taken.

An unorganized mob scarcely would do this, and would be still less likely to enforce the rule that every man present at every meeting should sign the minutes, thus assuming full individual responsibility for every action of the committee.

Regular trials were held, and every accused individual was allowed the widest latitude in obtaining witnesses, and in presenting their testimony, in which nothing was excluded.

…

Out of the records which she has unrolled, Miss Williams produces first the fact that the Committee of Vigilance of San Francisco was organized on June 9, 1851, “when California had been a recognized commonwealth of the Federal Union for exactly nine months, though for nearly five years she had been under the flag of the United States, and for three-quarters of a century before the American occupation, she had been a part of the great colonial system which Spain had planted upon the Western Hemisphere.”

The investigation of these records shows that the entire period from 1848 to 1856 was one of ceaseless struggle for the establishment and maintenance of order, during a time of transition from Spanish customs, laws and usages, to those of the Americans.

Two years of 1848 and 1849 Miss Williams considers a rather separate period within a period, occupied with the “struggle for organization.”

After this struggle for organization, when order was beginning to be established—but only in its beginnings—there arrived in San Francisco a horde of men from Australia, many of them convicts, the majority of them unscrupulous, to say the least, attracted to California by the discovery of gold.

The presence of these criminal characters in numbers in San Francisco brought about the necessity, in the minds of the Americans there, of an organization which, under the failure of the courts to perform their duty, could and would maintain such order as had been established.

This idea, doubtless, grew from the principles of organization, order and obedience to law, which these Americans—most of them transplanted from localities east of the Mississippi River—had inherited from their fathers, or had imbibed from their surroundings in their youth.

Thus, out of necessity for the protection of lives and properties, grew the first, and, possibly, more important, of the two Committees of Vigilance, that of 1851.

“The population of San Francisco, at this time,” said Miss Williams, “was about 23,000, gathered from all the ends of the earth. To this number must be added a constant swarm of non-residents, rushing from their ships to the mines, and then back again to take passage to other ports. To cope with all the criminal problems of the city, there was a force of about 75 policemen, and from statements made before the Committee of Vigilance, it is evident that some among these were confederates of the thieves.”

Oddly enough, however, the immediate cause of the organization of the Committee of Vigilance appeared almost simultaneously in three cities.

It came in San Francisco, through the delays in the trial of one Benjamin Lewis for arson; it arose in Stockton through demands that the rough element from Sacramento be suppressed, while Sacramento itself also urged that the criminals in all three cities be brought to book by popular movement.

“It did not originate,” says Miss Williams, “as is sometimes presumed, in the imagination of hot-headed extremists, who cowed the law-abiding community into temporary subjection. Extremists there were among the Vigilantes, but, as we study the records of their work we shall see that passion and violence were restrained to a surprising extent.”

In brief, the Vigilantes of 1851 were a body of responsible men of substance in the community, banded to establish and maintain American laws, customs, usages and justice among foreign criminals, not so very unlike the foreign criminal element abroad in this country today.

They believed in America for Americans, and an America of Americans, and they did not hesitate one second to risk their lives, their property, and their worldly all in compelling by force those who would not conform to American principles either to conform to them or pay the penalty for their crimes. . .

Of interest in this connection is the fact that about a score of the men who made up the Committee of Vigilance of 1851 were considered wealthy, while others made themselves prominent in business, the law, politics, or the professions in later years.

The majority were small business men, clerks, physicians and the like, who handed down little save their family names to the future.

…

The committee of 1851 drew up a brief but comprehensive constitution, embracing only five points, of which the first, stating the name and objects of the organization, reads:

“First—that the name and style of the association shall be the Committee of Vigilance for the protection of the lives and property of the citizens and residents of the city of San Francisco.”

The complete text of this constitution, which lack of space forbids publishing here, merely made a declaration of purpose. It outlined no program beyond the provision that a subcommittee should be on duty at all times, night and day, at a designated place, to receive reports of deeds of violence, and to summon the general committee of the association for consideration of cases requiring further action.

The need for action was shown by suddenness with which action came.

Taking one vivid bit from the continuous romance of the hand-written records of the committee, Miss Williams transcribes the first case to come before the Vigilantes, as follows:

“The meeting of Tuesday evening, June 9, 1851, adjourned after 100 men had signed the roll.

“While a small group yet lingered in the room, a startling knock beat upon the closed door, and when it was opened, two or three members of the committee entered, dragging between them a powerful and defiant prisoner, John Jenkins, who, that very evening, had entered the office of George W. Virgin, on Long Wharf, seized a small safe, and dropped with it into a boat lying at the end of the pier.

“Virgin, arriving in time, raised a cry while the thief was still in sight.

“Seeing that capture was imminent, Jenkins threw his booty overboard and surrendered to a boatman, John Sullivan.

“David B. Arrowsmith, and James F. Curtis, members of the committee, assisted Sullivan in securing the prisoner, and George E. Schenck, who met them as they emerged into Commercial street, urged them to take Jenkins before the committee, instead of to the police station, as had been their intention.

“The suggestion was adopted, and, in a few minutes after their organization, the newly pledged Vigilantes faced the first acute problem to arise under their self-assumed responsibilities.

“In this case there was no doubt as to the overt act of violence, nor as to the need for assembling the general committee.

“Suddenly the bell of the California Engine Company struck a signal unfamiliar to the ears of San Franciscans—two measured taps, a pause, and then the two notes again, until every man within its sound had been caught by the summons.

“Quickly, the monumental bell echoed the call, and all San Francisco swarmed into the streets, soon humming with humanity.

“Brannan served as chairman, Bluxome as secretary, and, behind locked doors in Brannan’s building, the thief went to trial immediately.

“A jury was selected; Schenck acted as prosecuting attorney, being officially appointed to the post; a jury was drawn, the evidence heard, and the verdict was ‘guilty.’

“In the course of the trial, Jenkins was shown to be an ex-convict from Australia and to have had an unsavory record in San Francisco.

“Members hesitated when William D. M. Howard stepped forward, threw his cap on the table, faced the meeting, and said, calmly and evenly: ‘Gentlemen, as I understand it, we came here to hang somebody.’

“The effect was instantaneous, and the meeting voted to hang Jenkins without delay.

“Brannan went out to a convenient sand hill and addressed the crowd, telling of Jenkins’ arrest, his trial and the verdict, laying before the people all the evidence which had been placed before the committee.

“Then he demanded approval or condemnation by the people of the action of the committee.

“His answer was a tumultuous ‘Yes,’ but with a few dissenting ‘Noes.’

“Later a coroner’s jury, of which T. M. Leavenworth was foreman, implicated some of the members of the Committee of Vigilance in the execution.

“The following day, the newspapers published the following resolution, signed by all the members of the Committee of Vigilance:

“‘RESOLVED, that we, members of the VIGILANCE COMMITTEE, remark with surprise the invidious verdict rendered by the coroner’s jury after their inquest upon the body of Jenkins, alias Simpton, after we have all notified the said jury and the public that we were all participators in the trial and execution of said Jenkins. We desire that the public will understand that Captain E. Wakeman, W. H. Jones, James C. Ward, Edward A. King, T. K. Bat telle, Benjamin Reynolds, J. S. Eagan, J. C. . Derby and Samuel Brannan, have been unnecessarily picked from our numbers, as the coroner’s jury have had full evidence of the fact that all the undersigned have been equally implicated, and are equally responsible with their above-named associates.’

“This resolution gave to the world the names of the men who had taken upon themselves the task of protecting lives and property and of restoring order to San Francisco.

“Their work, not only in the Jenkins case, but in others which followed thick and fast was approved immediately by the press and by the better element of the city, and their summary action in the case of the first criminal captured, no doubt went far toward preparing the city for the work the Vigilantes were still to do before either life or property could be safe in the San Francisco of 1851.”

=====

The California Diamond Jubilee Commemorative Silver Half Dollar Coin shows with an image of the Vigilance Committee’s hanging of James Stuart for assault, robbery and murder, July 1851.