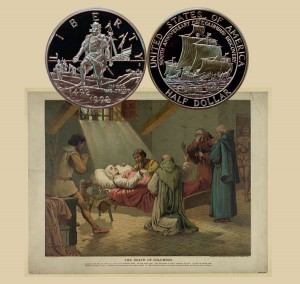

Today, the Columbus Commemorative Half Dollar Coin remembers the explorer’s last voyage home, begun 512 years ago.

From the Harper’s New Monthly Magazine of October 1892, an excerpt of Professor Dr. S. Ruge’s article titled “Columbus:”

=====

The question has in recent times been asked — it is a very unprofitable question —whether on his third and fourth voyages Columbus really set foot on the continent of America.

There can, of course, be no question about the first two voyages: he did not even get within sight of the coast.

But here we have a perfectly definite statement: “Two Indians carried me to Carambaru.”

He went on to the southern limits of the present state of Costa Rica, and there, in the island-studded Bay of Chiriqui, he heard the first tidings of the great ocean.

The account was indistinct enough, but it confirmed him in his opinion that he had reached the Golden Chersonesus, and that the sea on the western side must be (in modern phrase) the Bay of Bengal.

He was seeking for a channel by which he might make his way into this sea.

The coast abounds in gold. It received the name of Veragua after the Indian tribe who dwelt there.

The name is interesting because it was borne by the descendants of Columbus, the Dukes of Veragua.

In this case again Columbus did not see the consequences of his geographical error.

If, as he believed, he was, at the most, ten days’ journey from the mouth of the Ganges; if, as all his authorities agreed, he was on the Golden Chersonesus, half-way around the globe— then the earth could not possibly have so large a circumference as up to that time had been supposed.

He had already sailed half round it, and the direct voyage could be made from Spain in four or five weeks.

But he did not hesitate to complete the geographical structure which his imagination had raised.

From Jamaica he writes to the King and Queen, “The earth is not so large as is generally supposed.”

Amid frightful tropical thunderstorms Columbus worked his way east along the Isthmus of Panama.

The worm-eaten ships hardly kept above water, and he was continually obliged to run inshore to save them.

At last he was driven back to Veragua.

One ship after another was lost or had to be given up.

Several attempts at establishing a position on the coast of Veragua were frustrated by the stubborn resistance of the Indians.

The first ship was lost in April, 1503, on the coast of Veragua, when Columbus was starting for the second time in an easterly direction.

The second he had to leave at Porto Bello. With the only two remaining to him he endeavored to make his way from the Gulf of Darien to Jamaica, but he was driven out of his course, and reached, first, the Little Cayman Island south of Cuba.

Hence he hoped to sail straight home; but he was overtaken by bad weather, in which one ship lost three anchors.

He was obliged to steer for Jamaica. The water rose higher and higher in the hold, and the only possibility of saving the lives of his men lay in running the ships ashore.

This was on June 25, 1503, in the Bay of Santa Gloria, now called, after the discoverer, Cristobal’s Bay.

The ships sank and were lost, and their timbers served for the construction of forts against unexpected attacks of the Indians.

Thus ended in signal catastrophe the glorious work of the great traveler.

The discoverer of the New World was left a helpless shipwrecked man, with the remnant of his crew, on the shore of a savage island.

Fortunately it was not very far from his settlement at San Domingo. A message must be sent over, asking that the Admiral and his people might be rescued.

The perilous mission was undertaken by the faithful Diego Mendez, and on the second attempt successfully carried out in two canoes specially equipped for the sea-voyage.

Ovando suspected that the whole story of Columbus’s shipwreck was invented to give him an opportunity for visiting Haiti and taking up quarters there, and he let months pass before he sent the necessary help.

It was not till September 12, 1504, that Columbus began his last journey home, on another man’s ship, his whole squadron gone.

Ill, wretched, bent in body, and broken in spirit, he trod once more the soil of Spain.

No one troubled himself any longer about him; his arrival passed almost unnoticed.

Peter Martyr, who ten years before had boasted of his friendship, does not speak of the last voyages of the Italian in his letters.

His chief patron, Queen Isabella, died soon after he landed (November 26. 1504), and he had now no influential friends at court.

King Ferdinand had never taken a warm interest in his travels.

It cannot, indeed, be said without gross exaggeration that the Admiral lived in actual poverty, or that he lacked the necessaries of life.

But in Spain he altogether outlived his reputation, and he felt unutterably desolate.

When, on May 21, 1506, he died at Valladolid, the occurrence attracted no notice in the little town.

The chronicle of the town which covers this period, and which carefully records every trifle which served to swell the gossip of the place, does not give a syllable to the death of the discoverer of the New World.

Well for him that he did not live long enough to hear of the grossest insult which was offered to his name.

A year after his death the New World was named, not after the bold seaman Don Cristobal Colon, but after the Florentine merchant Amerigo Vespucci.

But enough!

We began with a quotation from Goethe; we may fitly end with one.

It has been proved in recent times that Columbus was not of noble birth; that he did not study in Pavia; that he was not a sailor from his boyhood.

We may feel convinced that he did not originate the plan of his voyage; that he was throughout the victim of erroneous cosmographical theories.

It may be granted that his mathematical and astronomical knowledge was weak, and his nautical performances not remarkable.

But still this remains to him: the resolution to do the deed; the invincible courage which made him persevere through years of scorn and insult, which made him devote his life to the idea.

His deed makes him immortal.

In Goethe’s play Faust is pondering over the translation of the first verse of St. John’s Gospel.

He finds the rendering “In the beginning was the Word” unsatisfactory; one after the other he tries “In the beginning was the Thought, the Power”; and at last finds the solution, “In the beginning was the Deed.”

By this deed of his, Columbus gave us the New World.

=====

The Columbus Commemorative Half Dollar Coin shows with an artist’s image of the elderly explorer on his death bed.