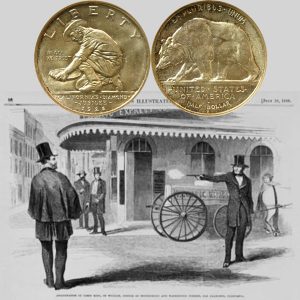

Today, the California Diamond Jubilee Commemorative Silver Half Dollar Coin remembers the Committee of Thirteen that resurrected on May 14, 1856 to provide vigilance against the rampant criminal activities.

From the History of the San Francisco Committee of Vigilance of 1851, A Study of Social Control on the California Frontier in the Days of the Gold Rush by Mary Floyd Williams, published in 1921:

=====

While Cora complacently awaited retrial thirteen other men in San Francisco were under indictment for homicide with small prospect for their conviction, and murders were so common in the state that the attempt to record them was abandoned.

James King of William, one time Vigilante, editor of the Bulletin and scourge of corruptionists, was himself fatally wounded on the afternoon of the fourteenth of May, 1856, by James P. Casey, a supervisor of the city, whose past record as a Sing Sing convict had been held up to public opprobrium by the militant reformer.

King’s personal qualities had won him many admiring friends, while his outspoken arraignment of political iniquity had made him a popular leader and hero. The cowardly attack that laid him at death’s door immediately invested him with the crown of a martyr.

As if in answer to the shot the bell of the Monumental Engine Company sounded once more the well remembered call to action, and in less than an hour an infuriated multitude surged about the county jail, clamoring for the instant execution of the assassin. Our old acquaintances Charley Duane and Edward McGowan were already reinforcing the guard at the door.

Detachments of the local military companies were rushed to the scene to hold the mob in check, but the men who hesitated before the rifles of the militia soon began to finger their own revolvers, and hysterical orators urged them to storm the building regardless of consequences.

Shouts of approval interrupted the speakers, cries of anger and oaths of rage arose in a hideous pandemonium above the surging mass, while in all the city there was not a single representative of the law whose promise of justice could ring true, or carry an assurance of righteous retribution that might invoke patience.

Suddenly this tossing sea of heads reflected the ripples of a hidden current from its outer margin. Men swayed and turned and bent their faces to whisper, and lifted them again, sane and human, and cleansed from the blood lust of the brute.

A brief message had passed from mouth to mouth, traversing the ranked thousands with incredible swiftness: “The Vigilance Committee has organized!”

In less than five minutes the fearful tension was relaxed, for in the Vigilance Committee rested assurance of justice and righteous retribution, and the men of San Francisco, still gathering by thousands during all that tragic evening, waited and trusted in the promise of its speedy resurrection.

The papers of the next day printed this notice:

The members of the Vigilance Committee, in good standing, will please meet at No. 105 1/2 Sacramento Street, Today, Thursday, 15 inst., at 9 A.M.

By order of the Committee of Thirteen.

San Francisco, May 14 [sic], 1856.

The archives of the Committee of 1851 make no mention of the Committee of Thirteen, which appears in history solely on this occasion.

From the statements of various Vigilantes, especially those of William T. Coleman and George W. Frink, we learn that after various sporadic gatherings and much fruitless discussion Coleman was induced to take the initiative in reorganization, largely on account of his standing in the old Committee, and of his membership in the last representative group, the Committee of Thirteen.

No other allusion to it occurs in the manuscript recollections. Bancroft did not explain it, and inquiries now fail to discover its personnel or its proceedings.

The Committee of Thirteen remains to this day a shadowy and unnamed power, but that very secrecy was symbolic of the mysterious bonds that survived the lapse of years, for on the afternoon of May 14, 1856, the Committee of Vigilance of 1851 was no longer a corporeal organization.

It was a name, and a memory; it was a spiritual force that restrained the men of San Francisco from mob murder in the twilight of that evening and enlisted them by thousands under the oath of the Vigilantes during the days to come.

The response to the printed call was instant and overwhelming. Old members hastened to the appointed place, and after a brief preliminary meeting threw open the doors for the reception of new registrants.

Before midnight two thousand names were enrolled, headquarters were secured, an Executive Committee was selected, and the rank and file were grouped into military companies of one hundred men each.

Coleman, who was by this time a merchant of wealth and prominence, reluctantly accepted the office of president, Bluxome was “Number 33, Secretary,” and many other former workers were placed in offices of responsibility.

It has been necessary to touch lightly on five years of California’s development in order to place the Committee of Vigilance of 1851 in its historical relation to the Committee of 1856.

The latter is usually designated the “Great Committee,” and the work of the former is obscured by the more spectacular features of the larger association.

Yet in spite of the silence that lay between the last notice of the Committee of ’51 and the call that rallied the Committee of ’56, the organic unity of the two bodies is proved by many tokens: by the personnel of the leaders, by the adoption of the old constitution, by the membership certificate with its significant “Reorganized,” and by the silver medal struck for the committeemen, which bears the old symbol, the Watchful Eye of Vigilance, encircled by the legend “Organized 9th June, 1851. Reorganized 14th May, 1856.”

The work of the Committee of 1856 is another story. Bancroft has told it in his own way in the second volume of Popular Tribunals; Royce has sketched it briefly, but well; and T. H. Hittell has given it at length with exact reference to contemporary newspapers and to the manuscript records, which were familiar to him as well as to Bancroft.

The Committee was supported by the active membership of eight or nine thousand men, about three quarters of all the white citizens of San Francisco.

Barricades of sand bags were erected around its headquarters on Sansome Street below Front, and armed men stood there on guard, so that Fort Gunnybags became a citadel that defied both civil and military authorities.

On the day that James King of William was borne to the grave the Committee hanged Casey, his assassin, and also Cora, who had killed William Richardson.

A few weeks later it inflicted the same punishment on two other murderers, Philander Bruce and Joseph Hetherington.

The latter had killed Dr. John Baldwin in a dispute over land titles, in August, 1853. On July 24, 1856, he also killed Dr. Andrew Randall, who had been robbed at Monterey by the Stuart gang in 1850.

The papers spoke of Hetherington as a “recipient of the old Vigilance Committee’s attention,” and Bancroft identified him with the witness of 1851.

If that identification is correct, a strange fatality made the former collector of Monterey the victim of the very man who had been chief informer against the gang that had despoiled him six years earlier.

These executions announced to the violent that money and influence and eloquent counsel might no longer be trusted to provide immunity from punishment.

But the Committee did not stop there.

Very early in its work it broke through the defense of secrecy that had baffled the investigations of grand juries.

It laid its hands upon an incriminating ballot box that was still stuffed with forged ballots; it obtained confessions from the ward heelers who had done the bidding of the powerful and efficient bosses; then it announced its intention of cleansing the city from the plague of political corruption.

It sent into exile over a score of the most valued tools of the machine. Among them were Charles Duane. who had evaded a like fate in 1851, and Rube Malony, who had been a committeeman in that year.

Ned McGowan, also conspicuous upon the early black list, was forced to take refuge in flight. When David S. Terry, justice of the state supreme court, stabbed S. A. Hopkins as the latter was arresting Malony, the Committee seized Terry, kept him in custody until Hopkins was out of danger, and liberated him only after the most bitter dissensions over his fate.

G. W. Ryckman, who refused to join the reorganized Committee, said that it even contemplated the arrest of Broderick, but such a radical step was never taken.

The General Committee adjourned sine die August 18, 1856.

Over six thousand men marched in the final parade, and the banner of 1851 led a company of one hundred and fifty members who represented the original organization.

As a factor in California life the Committee long survived the formal adjournment, and Executive meetings continued as late as November, 1859.

=====

The California Diamond Jubilee Commemorative Silver Half Dollar Coin shows with an artist’s portrayal, circa 1856, of the attack on James King.