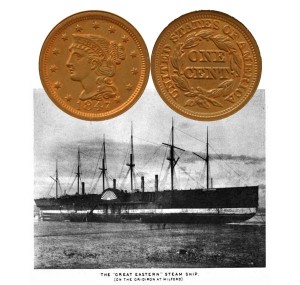

Today, the large cent coin remembers the men on the Great Eastern, their endeavors to lay the Atlantic Cable and their unfortunate damages on August 3, 1865.

From Diaries of Sir Daniel Gooch, Baronet, by Sir Daniel Gooch and Lady Emily Burder Gooch, published in 1892:

=====

Thursday, August 3d, 11 A.M.

I went to bed at nine last night, taking a book with me to read, but it was idle; my eyes might be on the page, but my thoughts were at the bottom of the Atlantic; and I put out my candle, and at once fell into a sound and comfortable sleep which lasted until daylight this morning.

Oh, what a hard and bitter disappointment this is to us all, more hard because so slight a matter has caused it.

We have not seen the third fault, and we do not know therefore if it was like either of the former ones.

The effect was like that of the first; it was a puncture into the copper wire, but there was no actual metallic connection between the copper and the iron wires.

At the time of the fault, Mr. Field was in the tank, it being his watch, and one of the men heard a click as if a piece of projecting wire struck the ring of the crinoline, and he called out ” broken wire ” to the man on deck.

He did not hear it, and the word was not passed on to the men at the paying-out machinery to relieve the pulleys.

Immediately notice was given from the electrician’s room that the insulation was bad, and the ship was stopped.

At the same time that this occurred, one of the men in the tank picked up off the coil a short piece of the wire of the cable, about one and three-quarter inches long, with one end freshly broken and the rest rusted down considerably in size, forming a taper piece of wire, quite sufficient to have punctured the core of the cable, and been thrown out in passing from the tank; and as the effect on the cable was such as this would produce, it is reason able to conclude that it was the cause.

If so, then we have three accidents, all very simple in themselves, all very probable, and all very simply prevented in the future.

I did not know before that the fracture of these steel wires was a very common occurrence in the manufacture and coiling of the cable in the ship, but there is no difficulty in coming to the conclusion that these solid steel wires are the mistake and defect in the cable, and had they been a strand of very fine material, a fracture could not have formed a puncturing instrument.

When they break they often assume this position. And it has been the practice to secure the end

down by a piece of sewing; but as the fracture is more likely to take place as the cable is running out, no one sees it, and the result must in some cases, out of the many that occur, be to drive them into the cable at the paying-out machinery.

We have now about 1100 miles of cable on board; I would cover this entirely with a sewing of hard cord, and make any new cable, as I said, with strand, instead of solid wire.

Nor have I any doubt that such a cable would be laid without any difficulty; we would have had none but for this one defect.

Weather having very little influence on this ship, and however bad it may be, I have no doubt the only effect would be to drive us a little out of our course, and so consume some more cable, there is nothing that can throw doubt on the possibility of laying a cable across the Atlantic; and as the insulation of this cable has gradually improved as it was put into deep water, until it is now twelve times better than the contract standard, a cheaper material might be used in the outer coatings of the core, and the whole cable be laid at a much less cost.

These will be all matters to think over and discuss when we get back.

After the fault was discovered yesterday, we at once got the cable round to the hauling-in machine at the bows of the ship, and a little over two miles was got in with great ease, the cable showing much less strain upon it than we found the first time.

It was then cut on board to see if the fault had come in.

This not being the case, we began to haul in again, but by that time, one o’clock, the wind had changed and freshened a little, and it was more difficult to keep the ship’s head in the position wanted.

The cable caught on one of the projecting hawse holes and across the stem. To relieve this, a man was sent down to make a chain fast to the cable below it.

This was done and the cable freed, and the part where the chain was fastened had been pulled inwards three or four yards, when the cable broke.

I have no doubt the chain had damaged it; it was a dangerous thing to use, but I am told a rope would not hold.

The ship was taken back about ten miles and a few miles to windward of our course, and grapnel irons lowered with 2500 fathoms of line, and the ship allowed to drift across the course we believed the cable to lie.

At daylight this morning we had drifted sufficiently far to have, crossed the cable, and we commenced to haul up our line.

One of the wheels in the machine broke and delayed us some time, as it was necessary to make use of the anchor capstan.

We are now slowly getting it up, and from the strain there is good reason to hope we have hold of the cable.

I cannot say I have the least hope of success, but we would not have been satisfied to leave it without a trial; but I fear, even if we have hold of it, the strain will be too much, and the line will fail before we get it on board.

It is very extraordinary how the weather seems to favor us; in all our difficulties the winds and sea have become calm.

When I went to bed yesterday morning at 2.30, it was blowing very hard, and the sea running high — in fact, as dirty a night at sea as you would care to be out in; yet by six o’clock it was perfectly calm, and has remained nearly so until now, and beautifully fine.

The last couple of hours have not been so fine; there is both more wind and sea, and the glass has gone down. It also rains, and looks dirty.

A few hours will tell us whether we get the cable on board or not, although we will probably make one more attempt if this fails.

There will be many anxious minds in England today, as I daresay this morning’s papers would state the cable was gone or in serious difficulties.

How one short hour has buried all our hopes, the toil and anxiety of the two last years all lost! This one thing, upon which I had set my heart more than any other work I was ever engaged in, is dead, and all has to begin again, because it must be done, and, availing our selves of the experience of this, we will succeed.

I must now return to England to receive the sympathy of my friends, not their congratulations, as I had so fondly hoped. The cable broke in lat. 51° 25′, long. 39° 1′.

Thursday night, August 3d.

There is no doubt we had hold of the cable this morning, and raised it 700 fathoms, when the strain was too much for our line, and it broke at one of the shackles.

This occurred about twelve o’clock.

We have resolved to try again, and have taken up a position nearer the end of the cable.

Where we tried before was about twenty-five miles from the end.

We are now about seven or eight miles, but unfortunately the wind has gone to the west, and as this would drift us in the exact line of the cable, it is no use letting down the grapnel iron, so here we are waiting for a change in the wind.

It would not be safe to steam across it, as our speed would be too much.

The day has been foggy, wet, and dreary, and the night is no better.

I have just had a solitary ramble for half-an-hour on deck, and shall get to bed.

Everyone on board, since our accident, has been very low in spirits, none more so than O’Neil.

I have not heard a note of music from him since, nor do any of them seem inclined for a rubber at whist, but they sit talking over our troubles.

If we had each lost a dear friend, we could not be a more melancholy party.

I certainly have no hope of getting up the cable. Two and a half miles is a great depth to fish. It takes us about two hours to get the line down, and double that time to lift it.

—–

Just a few days later he wrote:

—–

Tuesday, August 15th.

How time softens all disappointment!

I begin to look back upon our broken cable as a matter to be regretted, but not one to discourage me in the ultimate success of our work.

It is true we have failed to complete the cable to Heart’s Content; it is true we have laid 1200 miles of the most perfect cable ever laid under water; it is, I believe, true that we can come out with proper tackle and pick up the end, and go on to lay the next with certainty — this for a cost not exceeding £30,000.

It is, therefore, no failure, but a postponement of our final triumph; we are not beaten, but checked, and the final result is as certain to my mind as it ever was.

No doubt we were cast down by the fracture; it was very unexpected; but seeing, as we did from the first, the possibility of restoring it, why should we have made ourselves so miserable?

The human mind, thank God, is very elastic, and soon recovers from any shock.

We now feel to have only one thought, viz., the best way of completing our work, nothing doubting its success.

We have had a large amount of excitement today, actually saw two ships; one passed close under our bows, the other at some distance.

Our men having nothing to do, have been employed in getting the ship clean and all in ship-shape order, and we certainly look all the better for it; in fact, we begin to look very smart, and will be like a new ship when we arrive at Sheerness.

I hope we will have a good stiff westerly breeze to go up Channel, that we may show all the inhabitants of the towns on each side that we can still cut a dash with all our sails set, and show our noble old ship off to advantage.

No stars, but a loving good-night.

=====

The Large Cent Coin shows with an image of the Great Eastern, the ship used to lay the cable.