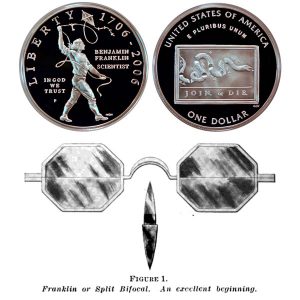

Today, the Franklin Scientist Commemorative Silver Dollar Coin remembers his letter of May 23, 1785 describing his glasses that allowed him to see both near and far.

From Bifocals, A History of the Scientific and Mechanical Development of the Double-vision Lens from the Time of Franklin, by Lucian Willis Bugbee, published in 1923:

=====

When old Mother Nature laid her plans for man’s vision she apparently did not consider the possibility of his ever becoming civilized. It seems as if she intended that man’s work should be completed at the age of forty-five, for she made no allowance for useful vision after that time.

The near vision demands of civilization made the loss of ocular accommodation, due to age, a serious matter. Many a brilliant man must have thereby been shelved at a time when his mental powers were at their best.

Samuel Pepys, whose famous diary gives us such an accurate picture of life in the Seventeenth Century, was just such a ease, a victim of the fetish of not prescribing “lenses too old for the eyes.”

Toward the end he says, on June 30, 1668, “My eyes bad, but no worse — only weary with working …. I am come that I am not able to read out a small letter, and yet my sight good, for the little while I can read, as ever it was, I think” and closes the diary with a tragic and pathetic entry resigning himself to the approaching blindness which should never have overtaken him had his case of accommodative asthenopia been sufficiently corrected.

Though the invention of opthalmic lenses was of inestimable value, the juggling of two pairs of spectacles must most certainly have proved a nuisance in those days of heavy, hand-forged, clumsy frames.

It is little wonder then that the wearing of glasses, put off for as long as possible, was considered the hall mark of old age.

It remained for one of the most brilliant minds of all times to solve the problems of both near and far vision in a single pair of glasses — Benjamin Franklin.

The invention cannot be better described than in the great American’s own words:

“I imagine it will be pretty generally true that the same convexity of glass through which a man sees clearest and best at the distance proper for reading is not the best for greater distances.

“I, therefore, had formerly two pair of spectacles which I shifted occasionally, as in travelling I sometimes read and often wanted to regard the prospect.

“Finding this change troublesome and not always sufficiently ready, I had the glasses cut, and half of each kind associated in the same circle, thus . . . by this means, as I wear my spectacles constantly, I have only to move my eyes up or down as I want to see distinctly far or near, the proper glasses being always ready . . .

“This I find more particularly convenient since my being in France . . . when one’s ears are not well accustomed to the sound of a language, a sight of the features of him that speaks helps to explain, so that I understand French better by the help of my spectacles.” (Letter to George Whately from Passey, France, May 23, 1785.)

Franklin never believed in restricting mankind’s benefit from his inventions by patenting them. It is, therefore, hard to understand why Dollond, the famous London optician whose discovery in 1758 of achromatic lenses revolutionized lens and instrument making, did not realize the value of Franklin’s invention enough to introduce it widely.

We know he was skeptical, for Franklin says in the above letter: “By Mr. Dollond ‘s saying that my double spectacles can only serve particular eyes. I doubt, (if) he has been rightly informed of their construction.”

Dollond through his skepticism allowed the idea to slip through his fingers into obscurity, thereby missing an opportunity which would have been both profitable to him and greatly beneficial to mankind.

Even today, one hundred and fifty years after its invention, the Franklin or Split Bifocal is met with at rare intervals, for its optical performance is excellent — even better than some more pretentious ones of today.

The coincidence of the optical centers at the dividing line avoids the prismatic difficulty of the “solid upcurve bifocal” which we shall next discuss.

Since only one kind of glass was used, color troubles were not present in the reading field. Definition was most keen, there being no high-temperature fusing processes to injure the polish of the lens surfaces.

A hot day caused the wearer no annoyance as there was no cement which, on melting, allowed the segment to slide. Moreover, it had no knife-edged segment to chip.

The defect which caused it to soon become obsolete was the unsightly dividing line, which collected dirt and whose shoulder reflected overhead light into the eye much as does the modern shouldered or depressed bifocal.

Then, too, at the slightest loosening of the frame, out dropped the lenses!

In the day when it was used, glasses were considered a necessary evil and their appearance from an artistic standpoint was apparently given scant consideration.

=====

The Franklin Scientist Commemorative Silver Dollar Coin shows with an image of the early bifocal glasses.