Today, the Lincoln Commemorative Silver Dollar Coin remembers the events prior to the dedication at Gettysburg.

His private secretary and others relate how President Lincoln began the first draft of his short but famous speech on November 17, 1863, just two days prior to the ceremony.

From Gettysburg and Lincoln: The Battle, the Cemetery, and the National Park by Henry Sweetser Burrage, published in 1906:

=====

On the contrary, however, Mr. John G. Nicolay, President Lincoln’s private secretary, who, as has been stated, accompanied the President to Gettysburg, says: ” There is neither record, evidence, nor well-founded tradition that Mr. Lincoln did any writing, or made any notes, on the journey between Washington and Gettysburg. The train consisted of four passenger coaches, and either composition or writing would have been extremely troublesome amid all the movement, the noise, the conversation, the greeting, and the questionings which ordinary courtesy required him to undergo in these surroundings; but still worse would have been the rockings and joltings of the train, rendering writing virtually impossible.”

Noah Brooks, in his Life of Lincoln, says that, a few days before the 19th of November, Mr. Lincoln told him that Mr. Everett had kindly sent to him a copy of his address in order that the same ground might not be gone over by both, but Mr. Lincoln added: “There is no danger that I shall. My speech is all blocked out. It is very short.”

When Mr. Brooks asked the President if the address was written, Mr. Lincoln replied, “Not exactly written; it is not finished, anyway.”

A part of the address, however, was written on the day before Mr. Lincoln left Washington for Gettysburg.

This much we know on the testimony of Private Secretary Nicolay, who a few years ago published a facsimile reproduction of this original draft of the President’s Gettysburg address. It reads as follows:

“Executive Mansion,

“Washington, . . . 1863.

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, upon this continent, a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that ‘all men are created equal.’

“Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of it, as a final resting place for those who died here, that the nation might live. This we may, in all propriety do. But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate — we cannot consecrate — we cannot hallow — this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have hallowed it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here; while it can never forget what they did here.

“It is rather for us, the living, we here be dedica— ”

The page closes with these words. Mr. Nicolay says: “The whole of the first page — nineteen lines — is written in ink in the President’s strong, clear hand, without blot or erasure; and the last line is in the following form: ‘It is rather for us the living to stand here,’ the last three words being, like the rest, in ink. From the fact that this sentence is incomplete, we may infer that at the time of writing it in Washington the remainder of the sentence was also written in ink on another piece of paper. But when, at Gettysburg on the morning of the ceremonies, Mr. Lincoln finished his manuscript, he used a lead pencil, with which he crossed out the last three words of the first page, and wrote above them in pencil ‘we here be dedica- ‘ at which point he took up a new half sheet of paper — not white letter paper as before, but a bluish-gray foolscap of large size with wide lines, habitually used by him for long or formal documents, — and on this he wrote, all in pencil, the remainder of the word, and of the first draft of the address, comprising a total of nine lines and a half.”

The part of the address on this second sheet is as follows:

“ted to the great task remaining before us — that, from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they here gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve these dead shall not have died in vain; that the nation shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Mr. Nicolay wrote his statement with reference to Mr. Lincoln’s address thirty years after the consecration of the cemetery at Gettysburg. He gives his recollection of the finishing of the address in these words:

“It was after the breakfast hour on the morning of the 19th, that the writer, Mr. Lincoln’s private secretary, went to the upper room in the house of Mr. Wills which Mr. Lincoln occupied, to report for duty, and remained with the President while he finished writing the Gettysburg address, during the short leisure he could utilize for this purpose before being called to take his place in the procession, which was announced on the program to move promptly at ten o ‘clock.”

It seems hardly possible that, with the quiet and leisure of the evening before, Mr. Lincoln would have left the preparation of the conclusion of his address until the busy moments of the after-breakfast hour of the next morning, with the exception of the last touches which doubtless occupied his attention.

Major W. H. Lambert of Philadelphia makes this statement: “The Hon. Edward McPherson and Judge Wills of Gettysburg are of the opinion that the address was written in Mr. Lincoln’s room at Judge Wills’s house, where he was guest during his stay in Gettysburg. There appears to be no doubt of the correctness of Mr. McPherson’s assertion that before retiring on the night of the 18th the President inquired the order of the exercises of the next day, and wrote out his remarks there, and it is probable that what he wrote was the final draft of his address before its delivery.”

When these words were written, Major Lambert had not seen Mr. Nicolay’s statement with reference to the first page of Mr. Lincoln ‘s original draft of the Gettysburg address. His language, however, implies an original draft.

Nor, evidently, had Mr. Nicolay any knowledge of the fact that in the evening of the 18th, Mr. Lincoln had asked Mr. Wills what was expected of him in connection with the consecration services, and had received from him writing materials in accordance with a request of the President. As all the evidence with reference to the composition of the original draft of the Gettysburg address is now in, therefore, the facts seem to be these: that on the day before he left Washington for Gettysburg, Mr. Lincoln, who had already “blocked out” his address, wrote in ink the first page on paper with the Executive Mansion letter-head, and he may have completed the address — probably did — on another sheet of the same paper.

At Gettysburg, however, where he went over the address again, he was dissatisfied with the conclusion, if the conclusion had been written; or, if it had not been written, he now completed the address, probably in the evening of the 18th, possibly on the morning of the 19th, in the house of Mr. Wills, using a lead-pencil, striking out, on the first sheet written in ink in Washington, the words “to stand here,” and adding the words in pencil, “we here be dedica-.”

This pencil change at the bottom of the first page was evidently a hurried one, “we” being used for “to,” but there is no evidence of haste either in the composition or the writing of the nine and a half lines on the second page.

=====

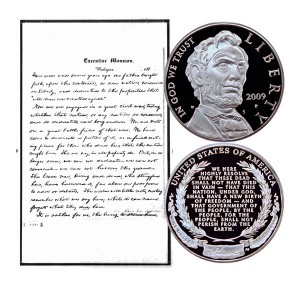

The Lincoln Commemorative Silver Dollar Coin shows with an image of the first page in ink of the Nicolay copy of the President’s Gettysburg address.