Today, the New York State Quarter Coin remembers the blizzard that began in the early hours of March 12, 1888.

From the book, New York in the Blizzard, Being an Authentic and Comprehensive Recital of the Circumstances and Conditions which Surrounded the Metropolis in the Great Storm of March 12, 1888, compiled by N. A. Jennings and McC. Lingan, of the New York Evening Sun, published in 1888:

=====

The First Day of the Blizzard

At little after 12 o’clock on Sunday night, or Monday morning, the severe rain that had been pelting down since the moment of the opening of the church doors suddenly changed to a sleet storm that plated the sidewalks with ice.

Then began the great storm that is to become for years a household word, a symbol of the worst of weathers and the limit of nature’s possibilities under normal conditions.

At a Quarter past 6 o’clock, when the extremely modified sunlight forced its way to earth, the scene in the two great cities that the bridge unites was remarkable beyond any winter sight remembered by the people.

The streets were blocked with snowdrifts. The car tracks were hid, horse cars were not in the range of possibilities, a wind of wild velocity howled between the rows of houses, the air was burdened with soft, wet, clinging snow, only here and there was a wagon to be seen, only here and there a feebly moving man.

The wind howled, whistled, banged, roared, and moaned as it rushed alone.

It fell upon the house sides in fearful gusts, it strained great plate glass windows, rocked the frame houses, pressed against doors so that it was almost dangerous to open them.

It was a visible, substantial wind, so freighted was it with snow.

It came in whirls, it descended in layers, it shot along in great blocks, it rose and fell and corkscrewed and zigzagged and played merry havoc with everything it could swing or batter or bang or carry away.

It was Monday morning, when a day of rest from shopping had depleted the larders in every house, and yet there were no milk carts, no butcher wagons, no basket-laden grocer boys, no bakers’ carriers.

In great districts no attempt was made to deliver the morning papers. The cities were paralyzed.

Few of the women who work for their living could get to their work places.

Never, perhaps, in the history of petticoats was the imbecility of their designer better illustrated.

“To get here I had to take my skirts up and clamber through the snowdrifts.” said a washwoman when she came to the house of the reporter who writes this.

She was the only messenger from the world at large that reached that house up to half past 10 o’clock.

“With my dress down I could not move half a block.”

It was so with thousands of women; the thousand few who did not turn back when they had started out.

Thus women were seen to cross in front of The Sun office and at many of the busiest corners up town. But all the women in the streets assembled together would have made a small showing. They are said to be much averse to staying in, but they stayed in as a rule yesterday.

At half past 10 o’clock not a dozen stores on Fulton street, in this city, had opened for business.

Men were making wild efforts to clean the walks, only to see each shovelful of snow blown back upon them and piled against the doors again.

“Have the girls come?” an employer asked of his porter. “Girls!” said the porter. “I have not seen a woman blow through Fulton street since I’ve been here.”

The street was dead. Here and there a truck moved laboriously, but more trucks were stuck in drifts and the horses were being led away from them.

The elevated roads were running trains semi-occasionally at this early hour, and mainly over only certain parts of their routes.

Only one East River ferry, the Fulton, was making its trips.

The Brooklyn elevated was chock-a-block with an engine broken down and a solid line of trains from the ferry to Greene avenue.

The big bridge was next to useless. A dense mass of men were packed in the Brooklyn depot, and a shuttle train, run by a dummy, was pecking dainty mouthfuls out of the great multitude, running now and then.

The cable whirred along, but it never would have done to hitch oars to it. That would simply have been to have the grips torn out of the oar bottoms.

The attendants would not allow any man to attempt to walk over the aerial footway.

The Fulton ferryboats picked their way across the turbulent river as blind men grope without their sticks. The water was black and boisterous, the air above It white and roaring.

When a boat would hold not another passenger It crawled out into the storm. The Staten Island boats ran in a desperate effort to mind their time table. Nothing was ever known to make any difference to a Staten Island boat except when the Westfield burst her boiler in 1871.

The Jersey ferries, at least these that wharf down town, ran as best they could, and they brought unofficial rumors that not a railroad wheel was turning in New Jersey.

You could not see New Jersey from New York ; you could not see Brooklyn or even Governor’s Island. But the storm was plain to see, to hear, to feel, and to fight.

What a storm! What a day! What a crippling of industry!

…

=====

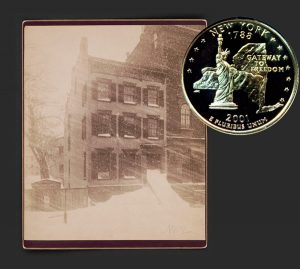

The New York State Quarter Coin shows with an image of a house in the city during the Blizzard of March 12, 1888.