Today, the Missouri State Quarter Coin remembers when the steamboat expedition left St. Louis to explore up the Missouri river on June 21, 1819.

From the History of Lafayette County, Mo., Carefully Written and Compiled from the Most Authentic Official and Private Sources compiled by the St. Louis, Missouri Historical Company, published in 1881:

=====

First Steamboats in Missouri.

Steam came at last, and revolutionized the business of navigation and commerce throughout the world.

The first steamboat that ever lashed the Missouri shore with its waves, or made our river hills and forests echo back her pulsating puffs, was the “General Pike,” from Louisville, which landed at St. Louis, August 2, 1817.

Such boats had passed a few times up and down the whole length of the Ohio river, and between Louisville and New Orleans, before this, so that the people of St. Louis had heard about them from the keel-boat navigators.

They were therefore overjoyed when the first one landed at the foot of their main business street, and thus placed them for the first time in steam communication with the rest of the civilized world.

The event was celebrated with the most enthusiastic manifestations of delight by the ringing of bells, firing of guns, floating of flags and streamers, building of bonfires, etc.

The second one, the “Constitution,” arrived October 2; and from that onward the arrival of steamboats became a very commonplace affair.

The first boat that ever entered the Missouri river was the “Independence,” commanded by Captain Nelson. She left St. Louis May 15, 1819, and on the 28th arrived at Franklin, a flourishing young city that stood on the north bank of the Missouri river, opposite where Boonville is now located.

There was a U. S. land office at Franklin, and it was the metropolis of the up-Missouri region, or as it was then called, the “Boone’s Lick Country.”

When this first steamboat arrived the citizens got up a grand reception and public dinner in honor of the captain and crew.

The boat proceeded up as far as the mouth of the Chariton river, where there was then a small village called Chariton, but from that point turned back, picking up freight for St. Louis and Louisville at the settlements as she passed down.

The town site of Old Franklin was long ago all washed away, and the Missouri river now flows over the very spot where then were going on all the industries of a busy, thriving, populous young city.

The second steamboat to enter the Missouri river (and what is given in most histories as the first) was in connection with Major S. H. Long’s U. S. exploring expedition, and occurred June 21, 1819, not quite a month after the trip of the “Independence.”

Major Long’s fleet consisted of four steamboats, the “Western Engineer,” “Expedition,” “Thomas Jefferson” and “R. M. Johnson,” together with nine keel-boats. The “Jefferson,” however, was wrecked and lost a few days after.

The “Western Engineer” was a double stern wheel boat, and had projecting from her bow a figure-head representing a huge open-jawed, red-mouthed, forked-tongued serpent, and out of this hideous orifice the puffs of steam escaped from the engines.

The men on board had many a hearty laugh from watching the Indians on shore.

When the strange monster came in sight, rolling out smoke and sparks from its chimney like a fiery mane, and puffing great mouthfuls of steam from its wide open jaws, they would look an instant, then yell, and run like deer to hide away from their terrible visitor.

They thought it was the Spirit of Evil, the very devil himself, coming to devour them. But their ideas and their actions were not a whit more foolish than those of the sailors on the Hudson river, who leaped from their vessels and swam ashore to hide, when Fulton’s first steamboat came puffing and glaring and smoking and splashing toward them, like a wheezy demon broke loose from the bottomless pit.

Major Long was engaged five years in exploring all the region between the Mississippi river and the Rocky Mountains which is drained by the Missouri and its tributaries; and his steamboats were certainly the first that ever passed up the Missouri to any great distance. Long’s Peak, in Colorado, 14,272 feet high, was named after him.

From this time forward the commerce and travel by steamboats to and from St. Louis grew rapidly into enormous proportions, and small towns sprung up in quick succession on every stream where a boat with paddle wheels could make its way.

For half a century steamboating was the most economical and expeditious mode of commerce in vogue for inland traffic; and Missouri, with her whole eastern boundary washed by the “Father of Waters,” and the equally large and navigable “Big Muddy” meandering entirely across her territory from east to west, and for nearly two hundred miles along her northwestern border, became an imperial center of the steamboating interest and industry.

=====

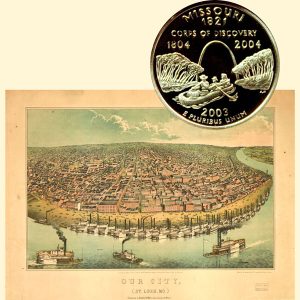

The Missouri State Quarter Coin shows with an artist’s image of St. Louis with many steamboats docked along the river, circa 1859.