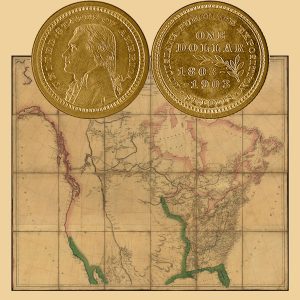

Today, the Louisiana Purchase Commemorative Gold One Dollar Coin remembers when Spain retroceded Louisiana to France with a treaty signed October 1, 1800.

Extracted from The History of Louisiana, by François-Xavier Martin, William Wirt Howe, John Francis Condon, published in 1882:

=====

LaSalle was exploring under the patronage of Louis Fourteenth and the Prince of Conti. He gave the name of Louisiana to the region he passed through, while in after years the name of his other patron was given to one of the streets of New Orleans.

The first important settlement resulting from these discoveries was made at Biloxi, on the northern shore of the Gulf, and now in the State of Mississippi. It was founded by Iberville in 1699, and was the chief town until 1702, when Bienville moved the headquarters to the west bank of the Mobile River.

The soil of Biloxi is exceptionally sterile, and the settlers seem to have depended mainly on supplies from France or St. Domingo. The French government, so distant and necessarily so ignorant of the true interests of the colony seemed intent on the search for gold and pearls.

“The wool of buffaloes,” says Martin, “was pointed out to the colonial officers as the future staple commodity of the country, and they were directed to have a number of these animals penned and tamed.”

To those who know Biloxi, there is something delicious in the idea of building up a colony there on pearls and ” buffalo wool.”

On the 26th September, 1712, the entire commerce of Louisiana, with a considerable control in its government, was granted by charter to Anthony Crozat, an eminent French merchant. The territory is described in this charter as that “possessed by the crown, between Old and New Mexico and Carolina and all the settlements, port, roads and rivers therein — principally the port and road of Dauphine Island, formerly called Massacre Island, the river St. Louis, previously called the Mississippi, from the sea to the Illinois, the river St. Philip, before called Missouri, the river St. Jerome, before called the Wabash, with all the lands, lakes and rivers mediately or immediately flowing into any part of the river St. Louis or Mississippi.”

The territory thus described “is to be and remain included under the style of the government of Louisiana, and to be a dependence of the government of New France, to which it is to be subordinate.”

By another provision of this charter “the laws, edicts and ordinances of the realm and the custom of Paris were extended to Louisiana.”

The grant to Crozat, so magnificent on paper, proved of little use or value to him, and of little benefit to the colony, and in 1718 he surrendered the privilege.

In the same year, on the 6th September, the charter of the Western or Mississippi Company was registered in the Parliament of Paris. The history of this enormous scheme, with which John Law was so closely connected, is well known.

The exclusive commerce of Louisiana was granted to it for twenty-five years, and a monopoly of the beaver trade of Canada, together with other extraordinary privileges, and it entered at once on its new domains.

Bienville was re-appointed governor a second time. He had become satisfied that the chief city of the colony should be established on the Mississippi, and so, in 1718, New Orleans was founded.

Its location was plainly determined by the fact that it lies between the river and Lake Pontchartrain, with the Bayou St. John forming a natural connection which extends a large portion of the way from the lake to the Mississippi. And even at this early day there was a plan of constructing jetties at the mouth of the great river, and so making New Orleans the deep water port of the Gulf.

It was about this time that the engineer, Pauger, reported a plan for removing the bar at the mouth of one of the Passes, by a system substantially the same as that so successfully executed recently, under the Act of Congress, by Captain James B. Eads.

It was a mooted question for some time, however, whether New Orleans, Manchac, or Natchez should be the colonial capital; but in 1722 Bienville had his way, and removed the seat of government to New Orleans.

In the same year, the place was visited by the Jesuit traveler, Charlevoix, who speaks of it as “this famous town which has been named New Orleans,” having been so called in compliment to the Regent Duke who was at the head of the French government during the minority of Louis Fifteenth.

It was famous, probably, at that time only, because the speculators of the Western Company had -puffed it into a premature reputation. Charlevoix himself was grievously disappointed with the town, and says in a melancholy way:

“It consists really of one hundred cabins disposed with little regularity, a large wooden warehouse, two or three dwellings that would be no ornament to a French village, and the half of a sorry warehouse which they were pleased to lend to the Lord,” — for a church — “but of which he had scarcely taken possession, when it was proposed to turn him out to lodge under a tent.”

He goes on, nevertheless, to make the prediction, that “this wild and dreary place, still almost covered with woods and reeds, will one day be an opulent city and the metropolis of a great and rich colony.”

The Western Company possessed and controlled Louisiana some fourteen years, when, finding the principality of little value, it surrendered it in January, 1732. The system which thus came to an end was essentially vicious, yet the supply of means to the colony was advantageous, and “it cannot be denied,” says Martin, “that while Louisiana was part of the dominion of France, it never prospered but during the fourteen years of the company’s privilege.”

In 1732, Le Page Du Pratz describes New Orleans in these words:

“In the middle of the city is the Place d’ Armes,” — now Jackson Square. “Midway of the rear of the square is the parish church dedicated to Saint Louis, where the reverend fathers, the Capuchins, officiate.

“Their residence is on the left of the church, on the right are the prison and guard house. The two sides of the square are occupied by two sets of barracks. It is entirely open on the side next the river. All the streets are regularly laid out in length and width, cross each other at right angles, and divide the city into sixty-six squares, eleven in length along the river, and six in depth.”

In 1763, occurred an event which left a deep impression on the history of Louisiana.

On the third of November of that year, a secret treaty was signed at Paris, by which France ceded to Spain all that portion of Louisiana which lay west of the Mississippi, together with the city of New Orleans, “and the island on which it stands.”

The war between England, France and Spain was terminated by the treaty of Paris, in February, 1764. By the terms of this treaty, the boundary between the French and British possessions in North America was fixed by a line drawn along the middle of the river Mississippi, from its source to the river Iberville, and from thence by a line in the middle of that stream and lakes Maurepas and Pontchartrain to the sea.

France ceded to Great Britain the river and port of Mobile and everything she had possessed on the left bank of the Mississippi, except the town of New Orleans and the island on which it stood. As all that part of Louisiana not thus ceded to Great Britain had been already transferred to Spain, it followed that France had now parted with the last inch of soil she held on the continent of North America.

The French inhabitants of the colony were astonished and shocked when they found themselves transferred to Spanish domination. Some of them were even so rash as to organize in resistance to the cession; and finally, in 1766, even went so far as to order away the Spanish Governor, Antonio de Ulloa.

But the power of Spain, though moving with proverbial slowness, was roused at last, and in 1769, Alexander O’Reilly, the commandant of a large Spanish force, arrived and reduced the province to actual possession.

The leaders in the movement against Ulloa, to the number of five, were tried, convicted and shot. Another was killed in a struggle with his guards. Six others were sentenced to imprisonment, and from that time “order reigned.”

The colony grew slowly from this time until the administration of Baron de Carondelet, but under his wise management, from 1792 to 1797, marked improvements were made.

The streets began to be lighted; fire companies were organized; the Canal Carondelet, connecting the rear of the city with the Bayou St. John and so with the Lake, was constructed; the defenses of the city were strengthened and a militia organized. In 1794, the first newspaper, the Moniteur, was established.

On the 1st October, 1800, a treaty was concluded between France and Spain by which the latter promised to restore to France the province of Louisiana.

France, however, did not receive formal possession until the 30th of November, 1803, when in the presence of the French and Spanish officers, the Spanish flag was lowered, the tri-color hoisted, and a formal delivery made to the French Commissioners.

But France did not remain long in possession. The cession to her had been procured by Napoleon, and he did not deem it politic to retain such a province.

While, therefore, it was being thus formally transferred, it had already, in April, 1803, been ceded to the United States, and on the 20th December, 1803, the United States took possession.

=====

The Louisiana Purchase Commemorative Gold One Dollar Coin shows with an image of a map showing North America, circa 1802.