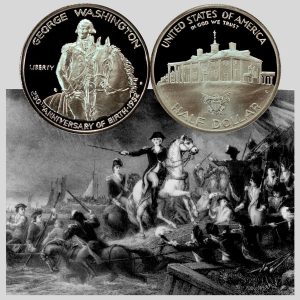

Today, the Washington Commemorative Silver Half Dollar Coin remembers his prudent retreat of the continental troops from Long Island on Thursday and Friday, August 29 and 30, 1776.

From the History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent, Volume IX, compiled by George Bancroft, published in 1875:

=====

In Philadelphia, rumor quadrupled his force; the continental congress expected him to stay the English at the threshold, as had been done at Charleston; but the morning of Thursday showed him that the British had broken ground within six hundred yards of the height now known as Fort Greene.

He saw that they intended to force his lines by regular approaches, which the nature of the ground and his want of heavy cannon extremely favored; he saw that all Long Island was in their hands, except only the neck on which he was entrenched, and that a part of his camp would soon be exposed to their guns; his men were cast down by misfortune, and falling sick from hard service, exposure, and bad food; his force was divided by a channel, more than half a mile broad, and swept by swift tides; on a change of wind, he might be encircled by the entrance of the British fleet into the East river; or ships which had sailed round Long Island into Flushing bay might suddenly convey a part of the British army to Harlem, or to Fordham heights, in his rear.

It was his first care to provide means of transportation for the retreat which it was no longer safe to delay.

Through Mifflin, in whom he confided more than in any general on the island, and who agreed with him in opinion, he dispatched, at an early hour, a written command to Heath, at Kingsbridge, “to order every flat-bottomed boat and other craft at his post, fit for transporting troops, down to New York as soon as possible, without the least delay.”

In like manner, before noon, he sent Trumbull, the commissary-general, to New York, with orders for Hugh Hughes, the assistant quartermaster-general, “to impress every kind of water-craft, on either side of New York, that could be kept afloat, and had either oars or sails, or could be furnished with them, and to have them all in the East river by dark.”

To prevent confusion, these orders were issued in such profound secrecy that not even his aids knew his purpose.

All day long he continued abroad in the wind and rain, visiting the stations of his men as before, and restraining their impatience.

Not till “late in the day” did he alight from his horse to meet his council of war at the house of Philip Livingston on Brooklyn heights.

The abrupt proposal to retreat startled the impulsive zeal of Morin Scott, and against his better judgment he objected to “giving the enemy a single inch of ground.”

But unanswerable reasons were urged in favor of Washington’s design: the Americans were invested by an army of more than double their number from water to water; MacDougall, whose nautical experience gave weight to his words, declared “that they were liable every moment, on the change of wind, to have the communication between them and the city cut off by the British frigates;” their supply of almost every necessary of life was scant; the rain which had fallen for two days and nights with little intermission had injured their arms and spoiled a great part of their ammunition; the soldiery, of whom many were without cover at night, were worn out by incessant duties and watching.

The resolution to retreat was therefore unanimous; yet, in the ignorance of what orders Washington had issued and how well they had been obeyed, an opinion was entertained in the council that success was not to be hoped for.

After dark, the regiments were ordered to prepare for attacking the enemy in the night; several of the soldiers published to their comrades their unwritten wills; but the intention to withdraw from the island was soon surmised.

At eight o’clock MacDougall was at Brooklyn ferry, charged to superintend the embarkation; and Glover of Massachusetts, with his regiment of Essex county fishermen, the best mariners in the world, manned the sailing-vessels and flat-boats.

The rawest troops were the first to be embarked; Mifflin, with the Pennsylvania regiments of Hand, Magaw, and Shee, the Delawares, and the remnant of the Marylanders, claimed the honor of being the last to leave the lines.

About nine, the tide of ebb made with a heavy rain and a strong adverse wind, so that for three hours the sail-boats could do little, and, with the few row-boats at hand, it seemed impossible to transport all the army; but at eleven, the northeast wind, which had raged for three days, died away; the water became so smooth that the row-boats could be laden nearly to the gunwales; and a breeze sprung up from the south and southwest, swelling the canvas from the right quarter.

It was the night of the full moon; the British were so nigh that they were heard with their pickaxes and shovels; yet neither Agnew, their general officer for the night, nor any one of them, took notice of the deep murmur in the camp, or the plash of oars on the river, or the ripple under the sail-boats.

All night long, Washington was riding through the camp, insuring the regularity of every movement.

Some time before dawn on Friday morning, Mifflin, through a mistake of orders, began to march the covering party to the ferry; it was Washington who discovered them, in time to check their premature withdrawing.

The order to resume their posts was a trying test of young soldiers; the regiments wheeled about with precision, and recovered their former station before the enemy perceived that it had been relinquished.

As day approached, the sea-fog came rolling in thickly from the ocean; welcomed as a heavenly messenger, it shrouded the British camp, completely hid all Brooklyn, and hung over the East river without enveloping New York.

When, after three hours or more of further waiting, and after every other regiment was safely cared for, the covering party came down to the water-side, Washington remained standing on the ferry-stair, and would not be persuaded to enter a boat till ‘they were embarked.

It was seven o’clock before all the companies reached the New York shore.

At four, Montresor had given the alarm that the Americans were in full retreat; but the English officers were sluggards, and some hours elapsed before he and a corporal, with six men, clambered through the fallen trees, and entered the works, only to find them evacuated.

From Brooklyn heights four boats were still to be seen through the lifting fog on the East river; three of them, filled with troops, were half-way over, and escaped; the fourth, manned by three vagabonds who had loitered behind to plunder, was taken; otherwise the whole nine thousand who were on Long Island., with their provisions, military stores, field-artillery, and ordnance, except a few worthless iron cannon, landed safely in New York.

“Considering the difficulties,” wrote Greene, “the retreat from Long Island was the best-effected retreat I ever read or heard of.”

=====

The Washington Commemorative Silver Half Dollar Coin shows with an image of the 1776 Long Island retreat from an engraving by J. C. Armytage.