Today, the Franklin Founding Father Commemorative Silver Dollar Coin remembers when he along with two grandsons stealthily set sail for France 241 years ago.

In Godey’s Magazine, December 1896, an excerpt from the article by George C. Lay entitled Franklin the Diplomatist:

=====

On September 26, 1776, Franklin, Silas Deane, and Arthur Lee were elected by Congress as commissioners to make a treaty of alliance with France, and to represent the United States at the French court.

At the age of seventy, on October 27, 1776, Franklin again braves the Atlantic and sets sail for France in the American frigate Reprisal, commanded by Captain Wickes.

As has been well said by Dr. Henry M. Leipziger, of New York, in his celebrated lecture on Franklin:

“We can point to nothing more impressive in the history of the time than this voyage, undertaken by Franklin when over threescore years and ten, with the British men-of-war sweeping the seas, with the certainty that if captured he would pay for his devotion to his country with his life.”

The English cruisers did indeed pursue the Reprisal, and the crew of the American vessel was several times beat to quarters, but the Reprisal was not overhauled, and after a short but rough voyage the vessel anchored in Quiberon Bay, in Brittany, and Franklin arrived in Paris on December 21, 1776.

During the period prior to the recognition of the United States as a nation, Franklin lived quietly at Passy, then a suburb of Paris, with his grandsons, William Temple Franklin, and Benjamin Franklin Bache.

His duties required much tact and skill, for at first the French king, Louis XVI, and his minister, Count de Vergennes, preserved outwardly the state of neutrality between England and France; but Franklin was able to secure loans for Congress from bankers in Paris amounting to 3,000,000 livres, and the French ports were open to American privateers.

The French minister sometimes ordered the American cruisers to leave French ports with their prizes within twenty four hours, but these orders were not enforced, and many violations of the laws of neutrality were winked at.

While the diplomatic life was quiet, and Franklin was careful not to give offence to the French Government, he became the idol of the French people.

He was universally admired and féted.

With the enthusiastic temper of the French, it was no wonder that Franklin became the rage of Paris.

He was not a mere passing fancy—-he had touched the heart and life of the people by his familiar writings; he was a philosopher and a great man, and the French made him a hero.

M. Lacretelle, a French historian, says: “Men imagined they saw in Franklin a sage of antiquity come back to give austere lessons and generous examples to the moderns. They personified in him the republic of which he was the representative and the legislator. They regarded his virtues as those of his countrymen, and even judged of their physiognomy by the imposing and serene traits of his own. Happy was he who could gain admittance to see him in the house which be occupied.”

Condorcet, the author of the “Life of Turgot,” the great philosopher and statesman of France, speaks of Franklin’s reception in France as follows:

“At his arrival he became an object of veneration to all enlightened men, and of curiosity to others. He submitted to this curiosity with the natural facility of his character, and with the conviction that in this way he served the cause of his country. It was an honor to have seen him. People repeated what they had heard him say. Every féte which he consented to receive, every house where he consented to go, spread in society new admirers, who became so many partisans of the American Revolution.”

Charles Sumner, in a learned and striking article in the Atlantic Monthly (“Monograph from an Old Note Book,” November, 1863), gave the origin and history of the celebrated inscription to Franklin’s portrait: Eripuit cœlo fulmen, sceptrumque tyrannis (He snatched the lightning from heaven and the sceptre from tyrants). It was composed by Turgot and appears in the above form in his published works.

Lacretelle says: “Portraits of Franklin were everywhere with this inscription, Eripuit cœlo, etc., which the court itself found just and sublime.”

Elegant fétes were given to the man who was said to unite in himself the renown of a great natural philosopher with “those patriotic virtues which had made him embrace the noble part of Apostle of Liberty.”

It was not strange that France should have honored the Apostle of Liberty.

“The great Revolution,” says Sumner, “was the outbreak of that spirit which had risen to welcome him. In snatching the sceptre from a tyrant, he had given a lesson to France. His death, when at last it occurred, was the occasion of a magnificent eulogy from Mirabeau, who, borrowing the idea from Turgot, exclaimed from the tribune of the National Assembly: ‘Antiquity would have raised altars to the powerful genius, who, for the good of man, embracing in his thought heaven and earth, could subdue lightning and tyrants.’ ”

Franklin gives us a humorous description of himself at this time in a letter written from Paris to Mrs. Thompson, in February, 1777:

“Figure me in your mind as jolly as formerly, and as strong and hearty, only a few years older; very plainly dressed, wearing my thin, gray, straight hair, that peeps out under my only coiffure, a fine fur cap, which comes down my forehead almost to my spectacles.”

=====

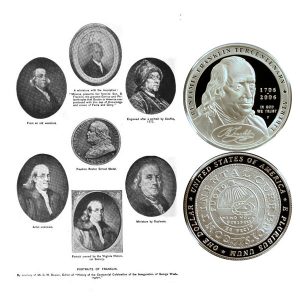

The Franklin Founding Father Commemorative Silver Dollar Coin shows with several images of the man including one with his fur hat.