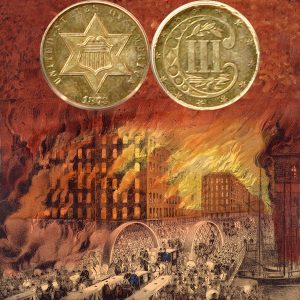

Today, the Three-Cent Trime Silver Coin remembers the start of the fire on October 8, 1871, that burned over 2400 acres and roughly 18,000 buildings in the main areas of Chicago.

From “The Great Calamity!” by Alfred L. Sewell, published in 1871:

=====

At about 9 o’clock on Sunday evening, October 8th, the fire-alarm was sounded for DeKoven-street, in the West Division, near the scene of the previous night’s fire, filled with shanties.

There, as is alleged, an Irish woman had been milking a cow in a small stable, having a kerosene lamp standing on the straw at her side. The cow kicked over the lamp, which exploded and set fire to the straw, and speedily the stable was on fire, and before the steamers of the Fire Department could reach the scene, the flames had communicated to an adjoining frame building, and thence, before the firemen could get the mastery of them, they spread rapidly northward and north-eastward, lapping up house after house, block after block, square after square, street after street.

This was still in the West Division — that is, west of the South Branch of the Chicago River. The destroyed property, thus far, consisted of lumber yards, planing mills, small frame residences, and various manufactories.

An area of a mile north and south, and a quarter of a mile east and west, embraces the extent of the conflagration in the West Division.

Reaching Van Buren street, the flames crossed the South Branch of the River at that point, a small row of frame buildings near the City Armory, (Police Head- quarters,) which was located on the corner of Van Buren and Franklin streets, being the first to catch fire.

Thence it communicated to the Armory building, constructed of stone, and to surrounding structures, and sped northward almost with the swiftness of the wind, reducing frame, brick, and stone buildings into heaps of ruins with amazing rapidity.

Opposite the Armory it exploded the huge receivers of the City Gas-Works with the noise of an earthquake.

The firemen and their steamers were utterly useless. They could do nothing to stay such a sea of flames as had now arisen, forced forward by a south-west wind that had now reached the violence of a gale, and which was scattering sparks, embers, and burning brands, for many blocks in its advance, over the roofs of the illuminated city.

Up the north-and-south streets of Market, Franklin, Wells, Griswold, LaSalle, Clark, Fourth Avenue, Third Avenue, Burnside, and Dearborn, and afterward up and down State-st. and Wabash and Michigan Avenues, it sped furiously and irresistibly, taking in its course the cross streets of Van Buren, Harrison, Congress, Jackson, Quincy, Adams, Monroe, Madison, Washington, Randolph, Lake, and South Water, on the Chicago River — sweeping the whole area — about two miles in length and half a mile wide, of all its noble public edifices, business palaces, and palatial residences — all its stately hotels, its huge Court-House, its great Government Custom-House and Post-Office, its scores of solid stone, brick, marble, and iron stores and banks, its Chamber of Commerce, its magnificent Opera-House, museum, and theaters, its grand churches, its newspaper and printing offices, its grain elevators, and immense railway depots — melting down in a few short hours the work of almost half a century — the very wealth, glory, and greatness of a city of over 300,000 people.

All night long the devouring flames raged, rushing furiously onward — a veritable sea of hissing, crackling, darting, roaring fire.

The cries of the terrified populace were drowned by the noise of explosions, the thunderings of falling walls, and the terrible roaring of the gale.

The conflagration had scarcely struck and enveloped one building before its darting tongues licked up its neighbor, and leaped hither and thither to the pitchy roofs and through the windows of a score of others, soon wrapping them in a common sheet of seething flame.

Buildings were blown up with powder to stay the progress of the burning, but without avail. The heat of the vast flaming sea was like a very hell, and nothing before it could withstand its power.

People in the streets half a mile in advance of it were blinded by the driving smoke and cinders, and almost roasted by the heat.

The great stone Court-House, in the center of a ten-acre park, isolated from all other buildings, took fire as if its roof and walls and the inside of its offices had been saturated with kerosene — so suddenly was it enveloped, and so swiftly did its destruction follow.

The great, solid, and supposed fire-proof Government building, containing the United States Custom-House and Post-Office, the destruction of which had been deemed impossible, after resisting the fire and heat around it for an hour, finally flashed into flame, and its interior was speedily emptied of its precious contents, and its broken and smoked walls were left standing as a monument to the fact that what human hands make strong, is, after all, as weak as a rope of sand when seized by the forces of the raging elements.

The Tribune building, a block distant, likewise deemed irresistibly fire-proof, also yielded and shared the general fate.

The magnificent hotels — the Sherman and the Tremont — each covering half a block — crumbled into shapeless masses of smoldering stone and brick, as effectually as if the lightnings of heaven had struck, or an earthquake had shaken them to pieces.

The stone-walled, iron-raftered and iron-roofed depot buildings of the Illinois Central and the Rock Island railways were swept down as if made of wood.

The five and six-story stone, brick, and marble business blocks on State, Lake, South Water, Dearborn, Clark, Randolph, Madison, Wells, LaSalle, Monroe, and Adams streets, and on the grand avenues nearer the Lake shore — scores of them — sunk down as if by magic, in the merciless embraces of the Fire-Fiend.

The immense grain elevators along the river and the South Branch, roofed and sided with iron, and deemed impregnable against all the forces of Nature, were reduced to piles of smoking incense to the god of Fire, in a few minutes after being struck by the heat and flame.

And now, sad, mournful sight! all those stately edifices, all those long, proud rows of costly depositories of a great city’s wealth, commerce, and life, are leveled to the earth, presenting a scene of ruin such as has never before encumbered the face of God’s earth.

All their rich goods, and wares, and commodities — the ever-tempting offerings of Commerce to man’s and woman’s power of possession have dissolved into imponderable atoms, and are mingling in the atmosphere — all gone, lost, vanished forever!

And those fine churches on the avenues — those capacious houses erected to the worship of the Most High God, but too often changed to the worship of the false gods of human pride, show, and worldly pomp and circumstance — how quickly their rich pews, ornamented pulpits, and costly organs were eaten up by the sweeping fire, and how easily their high-pointing spires and pretentious walls were brought to the ground!

The Fire-Fiend, like Satan, has no respect for churches, and in his visitations is no respecter of sects, names, or creeds. In this conflagration, the Presbyterian, Methodist, Episcopalian, Swedenborgian, Baptist, and Congregationalist, Catholic, Unitarian, Universalist, and Jew shared a common doom.

But the greed of the voracious Fire-Fiend was not yet satisfied. He had been devouring the South Division all night long, and toward noon of the next day, until it was all consumed.

The first rays of the morning dawn had scarcely begun to struggle through the dense smoke that covered the Lake, before he reached his fiery clutches across the main river into the North Division, first sweeping off all the bridges, and then seizing the store-houses and markets lining North Water and Kinzie streets, crushed them to mere piles of rubbish; and speeding onward furiously and more rapidly than before, under the force of the high wind, ere the sun, rising out of the Lake as red as a ball of fire, was an hour high, the flames had taken possession of all the streets for a mile northward.

The Chicago and North-Western Railway Company’s offices, freight houses, passenger depot, two huge grain elevators, many stores, lager-beer halls, breweries, store-houses, scores of fine residences, several large church, college, and hospital edifices, and public school buildings, were tumbled into ruins.

The City Water-Works, which received their supply from the great tunnel running two miles out into the Lake, shared the common misfortune at an early hour in the morning, and this added to the horrors of the occasion, for then the whole city was indeed at the mercy of the conflagration, the Fire Department being as powerless as a dead prize fighter, its water supply being cut off — yea, the water supply of the city itself destroyed!

This seemed to be the last drop in the bucket of human hope, and the general despair was complete.

And still onward swept the fiery billows — up, northward, through Pine, Rush, Cass, North State, North Dearborn, North Clark, North LaSalle, North Wells, North Franklin, North Market, and other great streets full of buildings, running northward from the main river between the North Branch and the Lake, and melting down to the ground all those compact cross streets running from the North Branch eastward to the Lake, including North Water, Kinzie, Michigan, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Ontario, Erie, Huron, Superior, Chicago avenue, the ten or a dozen streets between Chicago avenue and Division street, the ten or a dozen other streets between Division street and North avenue — up a dozen streets farther, and beyond Lincoln Park, in the northern limits of the city, four miles and a half from the locality where the conflagration began, where it finally exhausted itself, having burned up everything it could find to burn, and sparing the north-western corner of the North Division and the West Division, only because they were not in its line of march.

Thus through the North Division for a distance three miles long and about a mile wide, the devouring element rushed almost with the velocity of the wind, as it already had for a mile and a half one way and half a mile the other, in the South Division, laying waste a vast region which only a few hours before was the scene of happy life and trade.

It was early on Tuesday morning, October 10th, when the flames finally burned themselves out for lack of fuel in the wind’s direction, after having raged furiously for a space of about thirty-six hours.

=====

Note: In 1893 the reporter Michael Ahern retracted the “cow-and-lantern” story, but people continued to perpetuate the false report. Even though they were never charged, in 1997, the City Council exonerated the O’Leary family.

The Three-Cent Trime Silver Coin shows with an artist’s image of the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.