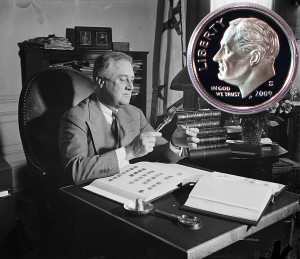

Today, on the anniversary of his birth, the Roosevelt Dime Coin remembers President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

He was a consummate collector of many things including coins but his more well-known interests included naval paintings, birds and stamps.

On the 100th anniversary, January 30, 1982, the Argus-Press printed:

He Shaped Destiny — Remembering Roosevelt

Hyde Park, NY (AP)

“The president of the United States is very disturbed,” Henry Morgenthau, Jr. told the trembling architect of the Rhinebeck, NY post office on April 25, 1938.

Hitler had invaded Austria a month before and 10 million Americans were out of work. At the moment, though, Franklin Delano Roosevelt had something else on his mind.

Roosevelt had learned that architect R. Stanley-Brown intended to disobey his instructions and use freshly quarried stone for the Rhinebeck post office, spoiling its Hudson Valley Dutch design.

“His instructions are that they should use old stone wall,” Treasury Secretary Morgenthau warned Stanley-Brown. “For God’s sake do, please.”

He did.

People surrounding Franklin Roosevelt learned quickly that the man, one of the dominant world figures of the 20th century, could be just as absorbed by post office design — or stamp collecting — as he was by world war and economic collapse.

“That’s the part of FDR that people don’t write about,” said Susan Brown, a museum curator here. “What’s so amazing is the way he would shut it all off. He could finish a meeting with Winston Churchill, go to his room and work happily on his stamps.”

Today, America celebrates the centennial of a man who shaped his home and county with the same intensity that he would later shape New York state, the nation and the world.

Franklin Roosevelt was born Jan. 30, 1882 in the gracious 35-room family home here, 70 miles north of New York City on the east bank of the Hudson River. Springwood was the lifelong residence of the only president elected to four terms.

Exactly a week before his centennial, fire ripped through the third floor and attic of the home. Water from fire hoses cascaded through the lower stories. Dozens of rescuers rushed into the burning home and salvaged nearly all the irreplaceable furnishings.

National Park Service staff have vowed to restore the national historic site. Roosevelt, an early backer of historic preservation, surely would have approved.

Before Sunday’s fire, Springwood remained almost exactly as it was the day Roosevelt left, down to the issues of Time magazine on the coffee tables and the World War II-era blackout curtains on the windows.

Visitors — there were more than 250,000 last year — have been struck by the sight of wheelchairs. They appear small and crude. One is made from a kitchen chair with its legs chopped off.

The sense of quiet tragedy is heightened by the sight of Eleanor Roosevelt’s bedroom, the one adjoining the president’s that she occupied after he was stricken by polio in 1921. It is as sparsely furnished as a guest room. In a sense, it was — mother Sara Roosevelt owned Springwood until her death in 1941 and Eleanor was the woman of the house for less than four years.

The main staircase is usually crowded with naval paintings — Roosevelt’s collection of 5,000 paintings and prints on seafaring is considered the world’s largest.

“FDR would have gone down in history as a great collector even if he had done nothing else,” historian Samuel Eliot Morison once said.

The president’s eclectic, hands-on approach to collecting stamps was mirrored in his New Deal efforts to lift America out of the Depression.

Laissez-faire economists were horrified with Roosevelt’s “pump priming” social-spending approach to reviving the national economy. Likewise, true stamp collectors were shocked that Roosevelt handled his collection with his fingers rather than tongs.

Roosevelt loved Springwood and planted more than half a million trees on the 1,000-acre estate. The greenery plan germinated in his mind — and the Civilian Conservation Corps he proposed as president put unemployed men to work planting trees across the country.

Hyde Park has the nation’s oldest oral history project. In 1947, National Park Service historians began making wire recordings of such people as the family chauffeur, Louis Depew, recalling Roosevelt’s battle to regain the use of his polio-stricken legs.

“One day, he hollered to me — he was out there swimming — and he says, ‘The water put me where I am and the water has to bring me back.’ That’s the very words he said,” Depew recounted for posterity.

There is also the voice of Robert McGaughey, another employee, revealing that he used to help the 40-year-old Roosevelt onto a tricycle and push him around the driveway.

“He thought he would bring his health back quicker that way by getting more control of his legs,” McGaughey recalled.

There is the farmer, Moses Smith, telling how Roosevelt so enjoyed Mrs. Smith’s crullers that he sent Eleanor over for the recipe.

Mike Reilly, head of the Secret Service detail at Hyde Park, recalls a state police car rounding a corner on two wheels in pursuit of the president’s famous blue Ford after Roosevelt — once again — gave his guards the slip.

And a house painter, John Clay, remembers a doting James Roosevelt nodding toward his 6- or 7-year-old son, Franklin:

“You know, Clay, he’s going to be president some day.”

=====

The Roosevelt Dime shows against a view of the president studying stamps circa 1936.