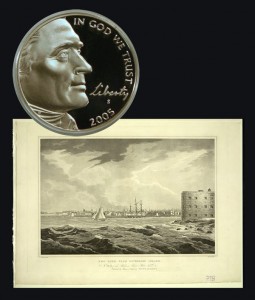

Today, the 2005 version of the Jefferson Nickel Coin remembers the British impressment of American sailors.

From The United States, its beginnings, progress and modern development by Jesse Ames Spencer:

=====

But this action of Congress had little effect, for on April 25, 1806, only a few days after the President had signed the act, a British vessel, the Leander, 50, scarcely two miles outside of Sandy Hook, attacked the sloop Richard from Brandywine, firing several shots at her, one of which beheaded the helmsman, John Pierce.

The Richard escaped, however, and brought the news to New York, where in a short time the wildest excitement prevailed.

Accordingly, on May 3, 1806, Jefferson issued a proclamation demanding the arrest of the captain of the Leander, Henry Whitby, and commanding the Leander and two other vessels, the Cambrian and the Driver, to depart from our shores and never again to enter our ports.

But the right of neutrals was not the only difficulty existing between England and our country.

Perhaps the most galling was what John Quincy Adams calls the claim to the “right of man-stealing from the vessels of the United States.”

For many years England had claimed the right to search foreign vessels for her seamen.

As early as 1790 she began the practice of dragging sailors indiscriminately from the decks of American ships, and ever since had carried on this practice in every portion of the civilized world with impunity.

When Thomas Pinckney was sent as minister to Great Britain he was instructed to insist that American ships made American seamen.

If it were apprehended that British subjects were being harbored on American vessels, British officers might be allowed to board the American vessels to count the crew; but no press gang should be allowed to board American vessels until the master had refused to deliver the supernumeraries and until an American consul had been summoned to witness the proceedings.

But war with France followed almost immediately, and the impressments continued.

In 1793 consuls were permitted to issue certificates of citizenship to native born citizens of the United States; but this was denied to be a consular power, was declared to be open to serious abuses, and the papers were not respected.

Even the Jay Treaty of 1794 was silent on the subject of impressment and on May 28, 1796, Congress passed an act instructing collectors of the ports to issue protections to seamen who were citizens of the United States, to keep a register, and to report once a quarter.

Furthermore, the President was authorized to appoint two agents to reside abroad who were to inquire into the situation of impressed American sailors and report to the Secretary of State.

Between 1796 and 1801, under the provisions of this act, 35,900 seamen were registered and the release of 1,940 was demanded by the agent in London.

In spite of this, however, the certificates were disregarded, and hundreds of seamen were impressed by the British and were never restored.

What made this worse was the fact that there were so many desertions from the English navy.

England claimed that she had the right to recover her deserters, which was not denied, but she went too far in trying to fill the places of deserters from the ranks of native American seamen.

Naturalization papers and protections were disregarded, such men as caught the fancy of the officers being taken off.

Both countries expressed the utmost anxiety to find a remedy.

The American minister, Rufus King, believed that the time had arrived when an agreement to stop the evil could be reached.

But just at this time Pitt retired from office, Addington took his place, Lord Hawkesbury became foreign secretary, and all the parlor talk went on without in the least changing the state of affairs.

Furthermore, British sailors were openly encouraged to desert; and so widespread did this custom become that Edward Thornton, the British charge, declared that in every American port this means was adopted to frighten British vessels from our shores and to prevent them from coming into competition with American shipping.

The Administration was little disposed to stop the abuse, Virginia being even allowed to pass an act providing that whoever delivered up or caused to be delivered up any free person for transportation beyond the sea, was guilty of a felony and on conviction should be sentenced to ten years’ imprisonment; furthermore, if the person so surrendered should be put to death, the felon should suffer death for having aided and abetted a murder.

Thus matters stood in 1803, when the peace of Amiens was broken and France and England again went to war.

Knowing that war was coming, King early in 1803 renewed negotiations and was almost successful in his efforts.

But when it came to signing a convention the British representative insisted that the Narrow Seas should be explicitly exempted from the provision against impressment.

To this King would not consent, and thus the negotiation failed.

Shortly afterward King was succeeded by James Monroe as minister to England.

Monroe was to begin negotiations by offering a commercial convention on a plan suggested by Madison.

The first article forbade impressment on the high seas; another prescribed the methods of searching a vessel; a third gave a list of such articles as were to be considered contraband of war; a fourth defined a valid blockade; a fifth denied protection to naval deserters; and a sixth denied protection to deserters from the army.

The convention was to remain in force eight years. Monroe laid this matter before Lord Hawkesbury, but before he could accomplish anything the ministry changed; Addington was succeeded by Pitt, Lord Hawkesbury was succeeded by Lord Harrowby, and the new secretary refused to consider the proposed convention.

Monroe was then called to Madrid by the quarrel between Charles Pinckney and Cevallos, and did not return to England until July of 1805. When he did return he found that the vice-admiralty court of Newfoundland had condemned the Aurora, that the Essex case had been decided, and that Lord Harrowby had been succeeded by Lord Mulgrave as Secretary of Foreign Affairs.

The case of the Aurora was the result of the action of a New York marine insurance company. The company complained of large losses because French frigates and privateers captured ships on which it had risks.

The company requested the British consul to have an English ship stationed off the port to keep the Frenchmen away.

Two vessels were sent and about the middle of June of 1804 the Cambrian, a 44, and the Driver, an 18, anchored near two French frigates then in port.

Shortly after a British vessel named the Pitt entered the Bay and was searched by an armed party from the Cambrian.

Twenty sailors were impressed and when the revenue and health officers attempted to board the Pitt they were driven off by armed sailors.

In condescending to apologize for this outrage, the captain of the Cambrian (Bradley) said that his people were ignorant of the law and did not know that an English ship ever could be subject to the authority of the United States; but he would not release the impressed sailors until the British consul informed him that he must.

The United States then complained; the captain was recalled (and promoted); and Congress passed the act of March 1805 to preserve peace in the ports and harbors of the United States.

When this law was sent to Monroe to be explained to the British ministry, he was instructed to protest against the decision in the Aurora case.

While Spain was at war with Great Britain, this ship had brought a cargo of Spanish goods from Havana to Charleston, landed the produce, paid the duty, re-shipped the cargo, received back the duty with the exception of 3 1/2 percent retained on articles exported after importation, and sailed for Barcelona, Spain.

On the way she was captured by an English cruiser, sent to Newfoundland, and condemned on the ground that the landing of her cargo and the paying of the duty did not break the continuity of her voyage, which, being thus continuous, was direct and illegal.

Should this decision be confirmed by the court of appeals, it would bring untold hardship and loss to American trade.

But the decisions of the Newfoundland court in the cases of the Essex and Mercury had been affirmed, and by the time Monroe protested to Lord Mulgrave regarding the Aurora this had become the settled policy of England.

The old troubles were gone over time and again by Monroe, but nothing definite could be agreed upon.

In January of 1806 Pitt died, and in February he was succeeded by Charles James Fox.

To him Monroe again presented the complaints, but was again subjected to the same irritating delays. In April of 1806 the Non-importation Act was passed by Congress and William Pinkney joined Monroe to settle all matters of difference between the United States and Great Britain.

On May 17, 1806, while Monroe was awaiting the arrival of Pinkney, Fox served formal notice on Monroe that England had declared the whole coast of Europe, from the Elbe in Germany to the Brest in France (about 1,000 miles), in a state of blockade.

The coast between the Ostend and the Seine had already been blockaded, no neutral ship being allowed into the ports and rivers of this region for purposes of trade.

In any other port or river from the Brest to the Elbe neutral ships might still go, if they did not come from or did not intend to go to a port then in the possession of England’s enemies.

American vessels, therefore, might continue to enter the Brest or Embden, Amsterdam or the Elbe; but their cargoes must have been made or grown in the United States or be British products.

Monroe was greatly alarmed and pressed for a settlement of affairs, which was again postponed. Hardly had Pinkney reached London (in June) when Fox died and was succeeded by Canning.

Meanwhile the President instructed the envoys to enter into no treaty regarding impressment 4 which did not absolutely secure American citizens against any and every exercise of this odious claim of Great Britain.

…

=====

The 2005 Jefferson Nickel Coin shows with an artist’s view of the New York harbor, circa 1820s.