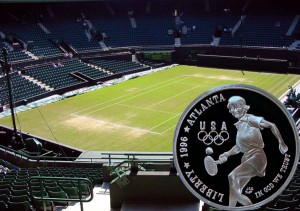

Today, the Tennis Commemorative Silver Dollar Coin remembers the first tennis tournament that began on July 9, 1877 at Wimbledon.

In the early years of the game, there were many changes as evidenced by the following article in the 1890 Baily’s Magazine of Sports and Pastimes:

=====

To compare the best players of today with those of the early years of lawn tennis is unfortunately well-nigh impossible.

The game is, in its essential conditions, vastly different from that which was played at Wimbledon in 1877, or even in 1881.

When the net was 5 ft. high at the posts, and 3ft. 3in. in the middle, the old tennis style of game was in vogue.

The object of the player was to drop the ball over the net with as much “out” or “screw” on it as possible.

It was Mr. S. W. Gore, the winner of the championship in 1877, who first discovered the power of volleying at the net against such tactics as these.

His successors, Messrs. P. F. Hadow and J. T. Hartley, had recourse to “lobbing” in order to frustrate this maneuver, and owed their victories to the untiring accuracy with which they could return the ball, at a pace which would now be considered decidedly slow, to the vicinity of the base line.

In 1878 the net was lowered by 3 in., and, in order to deprive the over hand service of its terrors, the service line, which had been originally placed at 26 ft. from the net, was brought 4 ft. nearer.

A further reduction in the height of the net to 4 ft. at the posts was made in 1880, when the service line was brought to a distance of 21 ft. from the net. It is from the following year that the modern style of game dates its origin.

The changes in the laws had apparently disposed finally of the volleyer, and what was then considered his unscientific system of play, when, to the consternation of the legislators, the brothers Renshaw arose to upset their calculations.

By volleying the ball at or near the service line, Mr. W. Renshaw was able, in 1881, to defeat, more or less easily, all his opponents of the old school and win the championship, Mr. H. F. Lawford alone making a good stand against him.

The days of interminable rallies of fifty or sixty strokes—an instance is recorded of a series of eighty-one returns in a match between good players—were over; but in the place of the monotony of unvaried back-play, the tyranny of the volley seemed to threaten the ruin of the game.

To obviate this danger the All-England Club made a final alteration in the height of the net, which was reduced to 3 ft. 6 in. at the posts. The volleyers, however, for the time more than held their own, and Mr. E. Renshaw came out as the winner of the All Comers’ prize at Wimbledon, and the challenger of his brother for the Championship.

At length, however, back-play, mainly through the example of Mr. Lawford, regained some of its old effectiveness. It was demonstrated by this player that any volleyer could be passed or driven from his post of vantage, by hard and accurate drives down the side lines; and although Mr. Renshaw retained the championship until 1887, when he was prevented by an injury from competing, he could only do so by combining his great rival’s tactics with his own.

From about the year 1884 it has been universally recognized that no player can attain the first rank without mastering both the volley and the hard drive from the base-line.

The consequence has been the elevation of lawn tennis from an affair of more or less pure dexterity to a game of almost infinite variety, in which activity and a good eye are less valuable than experience, quickness of judgment, steady courage, and fertility of resource.

Between equally matched players of any considerable degree of skill, the game becomes a struggle for position. By persistently driving the ball to the extreme corners of the court, each antagonist will strive to keep the other outside the base-line, until a short return gives the opportunity for the coup de grace in the shape of a “smash,” or an unreachable cross volley.

To run in to the service line after a weak or merely defensive stroke is fatal ; before making any such aggressive movement it is necessary to have clearly dispossessed your opponent of the attack, and to have got it into your own hands.

As in chess, one must penetrate the enemy’s designs, and discover his weak points, but with this difference, that not minutes, but the fraction of a second, is all the time allowed for reflection and the counter move.

Of the ruses and stratagems that are found serviceable there is no end. Not only does it avail to play to an antagonist’s weak back-hand, but in some cases he may be lured to his own ruin by the tempting bait of a ball similar to that of which he has just scored a point with an unusually brilliant return.

The latest addition to the tactics of the game is the perfection of stroke known as the “lob.” The difficulty of making a fast and accurate return off a high-tossed ball has been known for some years past; but the knowledge was not practically utilized until the defeat of Mr. Hamilton by Mr. Ernest Renshaw, at Wimbledon, the year before last.

A much more liberal use was made of this stroke by Mr. Barlow last year, who, finding “ lobs ” profitable at the Beckenham tournament, against his old rival and former conqueror, Mr. Meers, tried them with success against Mr. Hamilton at the Championship meeting.

In Mr. Barlow’s hands the lob becomes an attacking move. His opponent is not only driven from position at the service line to the back of the court, but finds himself called upon either to perform the feat of placing a vertically descending ball neatly down one of the side lines, or of lobbing in turn.

Should he choose the latter alternative, he must beware of tossing the ball into the middle of the opposite court, where the original lobber has meanwhile taken his stand, in the hope of some such opportunity for a “smash.”

To find the appropriate answer to the lob, or, in other words, to acquire the knack of hitting it back with certainty and pace, is one of the problems of the immediate future; and there are already several players who have made considerable progress in this direction.

Another stroke of which much is hoped, but which has hardly ever as yet been seen in match play, is that known as the “drive volley.”

It is nothing more nor less than the swift return in the volley of a good-length ball, which if allowed to drop would touch the ground near the base line. In practice it is often attempted, and occasionally achieved as a tour de force, but no player has mastered it sufficiently to run the risk of failure in the crisis of a close match.

When, if ever, it is brought to perfection, it will confer on its exponent the power of exchanging the defense for the attack almost at will.

Whatever may be the future developments of the single game…

=====

The Tennis Commemorative Silver Dollar Coin shows against a modern day view of Wimbledon.