Today, the Lincoln Commemorative Silver Dollar Coin remembers the flight, capture, escape and re-capture of John H. Surratt, believed to be an accomplice in the assassination of President Lincoln.

In the book, The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, Flight, Pursuit, Capture, and Punishment of the Conspirators, published in 1901, Osborn Hamiline Oldroyd described the chase and capture of Mr. Surratt.

=====

Early in November, 1866, General Rufus King went to Cardinal Antonelli and told him who Surratt was, asking him whether, upon the authentic indictment or the usual preliminary proof, and at the request of the State Department at Washington, he would be willing to deliver up John H. Surratt.

Antonelli frankly replied in the affirmative, and added that there was, indeed, no extradition treaty between the two countries, and that to surrender a criminal where capital punishment was likely to ensue was not exactly in accordance with the spirit of the Papal Government, but that in so grave and exceptional a case, and with the understanding that the United States Government under parallel circumstances would do as they desired to be done by, a departure would be made from the practice generally followed.

General King requested, as a favor to the American Government, that Surratt should not be discharged from the Papal service until further communication from the State Department, and His Eminence promised to advise with the minister of war to that effect.

The cardinal went with the information to the Pope on the 9th of November.

General King again called upon the cardinal, and was by him informed that John Watson, alias John H. Surratt, had been arrested by his orders, and while on the way to Rome had made his escape from the guard of six men in whose charge he had been placed.

At four o’clock on the morning of the 8th of November a sergeant and six men knocked at the gate of the Velletri prison, which opens on a platform which overlooks the country.

A balustrade prevents promenaders from falling on the rocks, situated at least thirty-five feet below.

After leaving the gate of the prison Surratt made a leap and cast himself into the void, landing on a ledge of rocks projecting from the face of the mountain, where he might have been seriously injured, but gained the depths of the valley.

The refuse from the barracks accumulated on the rock, and in this manner his fall was broken. Had he leaped a little farther he would have fallen into an abyss.

Patrols were immediately organized, but in vain. He was tracked from Velletri to Sora and Naples, stopping at the latter place for a few days, when he left on the steamer Tripoli for Alexandria, Egypt, under the name of Walters.

Surratt went to Naples on the 8th of November, dressed in the uniform of the Papal Zouaves, having no passport, but stating that he was an Englishman who had escaped from a Roman regiment. He said that he had no money, and the police, being somewhat suspicious of him, gave him (at his own request) lodgings for three days in prison.

He stated that he had been in Rome two months; that being out of money he enlisted in the Roman Zouaves, and was put in prison for insubordination, from whence he had escaped by jumping from a high wall, in doing which he hurt his back and arm.

On the third day he asked to be taken to the British consulate, to which place one of the police went with him. Here he complained of his confinement, stating that he was a Canadian, and the consul claimed his release as an English subject.

In the meantime the police had found that he had twelve scudi with him, and, on asking him why he went to prison, he replied that he wished to save his money.

He remained in Naples until Saturday, the 18th, when, through the influence of the English consul, he obtained passage on the steamer Tripoli to Alexandria, at 9 o’clock p. m., some English gentlemen paying for his board during the voyage, and giving him a few francs.

The United States consul at Malta, William Winthrop, was informed by the consul at Naples of Surratt’s departure, but he was hampered by legal quibbles and the slowness of the proper authorities to act, and Surratt left Malta, in the steamer which brought him, at 4 p. m. on the 19th.

On board the steamer Tripoli, while coaling at Malta, Surratt gave his name to the superintendent of police as John Agostina, a native of Canada.

The steamer reached Alexandria, Egypt, on the 23d of November, and on the 27th Charles Hale, consul-general of the United States at that place, went on board and arrested Surratt, who was still dressed in the uniform of a Zouave.

Mr. Hale found it easy to distinguish him among the seventy-eight of the third-class passengers by his Zouave uniform and his almost unmistakable American type of countenance.

Mr. Hale at once said: “You are an American.” Surratt said: “Yes, sir; I am.”

Mr. Hale said : “You doubtless know why I want you. What is your name?” He replied promptly, “Walters.”

Mr. Hale then said: “I believe your true name is Surratt,” and in arresting him mentioned his official position as United States consul-general.

Surratt and the other third-class passengers had been in quarantine four days, but when arrested the director of quarantine speedily arranged a sufficient escort of soldiers, by whom the prisoner was conducted to a safe place within the quarantine walls.

December 2 the following telegram was received at Washington:

To Seward, Washington. Have arrested John Surratt, one of President Lincoln’s assassins. No doubt of identity. Hale, Alexandria.

The appearance of the prisoner at the time of his arrest answered well the description given of him by Weichmann in Pittman’s report of the trial of the conspirators, and officially sent by the Government to the various consuls: “John H. Surratt is about six feet high, with very prominent forehead, a very large nose, and sunken eyes. He has a goatee, and very long hair of a light color.”

On the 29th Surratt was transferred, under a sufficient guard, from the quarantine grounds to the Government prison.

On December 4 Secretary Seward telegraphed Minister Hale at Alexandria, Egypt, that the Secretary of the Navy had instructed Admiral Goldsborough to send a proper national armed vessel to Alexandria to receive from him John H. Surratt, a citizen of the United States.

Surratt remained in safe confinement until the 21st of December, when he was delivered by Mr. Hale on board the corvette Swatara, and taken to America, landing at Washington, D. C.

The criminal court for the District of Columbia, before which the trial of John H. Surratt took place, was opened at ten o’clock, June 10, 1867, and closed August 11, lasting sixty-two days.

…

Over two hundred witnesses were examined. The jury disagreed, standing eight for acquittal and four for conviction.

Of the four who were for conviction, none were born in the South; of the eight for acquittal, all except one were natives of Maryland, Virginia, or the District of Columbia.

Surratt was kept in the Old Capitol Prison for some months, but was finally liberated on twenty-five thousand dollars bail.

His counsel were General Merrick and John G. Carlisle. He was again arraigned for trial.

The prosecution declined to proceed upon the charge of murder of Mr. Lincoln, and proposed to try him upon the charges of conspiracy and treason.

But his counsel showed that the law in such cases required that the indictment should be found within two years from the time of the alleged offense, unless the respondent was a “fugitive from justice.”

More than this time had intervened, and there was no averment in the indictment that he was a fugitive. The court thereupon discharged him.

From a lecture delivered by John H. Surratt a few years since, we quote a little from his story, which shows the work he did for the Southern cause, to which he was very much devoted:

“At the breaking out of the war I was a student at St. Charles College, in Maryland, but did not remain there long after that important event. I left in July, 1861, and, returning home, commenced to take an active part in the stirring events of that period.

“I was not more than eighteen years of age, and was mostly engaged in sending information regarding the movements of the United States army stationed in Washington and elsewhere, and carrying dispatches to the Confederate boats on the Potomac.

“We had a regularly established line from Washington to the Potomac, and I, being the only unmarried man on the route, had most of the hard riding — sometimes in the heel of my boots; sometimes between the planks of the buggy.

“I confess that never in my life did I come across a more stupid set of detectives than those generally employed by the United States Government. They seemed to have no idea whatever how to search me.

“In 1864 my family left Maryland and moved to Washington, where I took a still more active part in the stirring events of that period. It was a fascinating life to me.

“It seemed as if I could not do too much or run too great a risk.”

=====

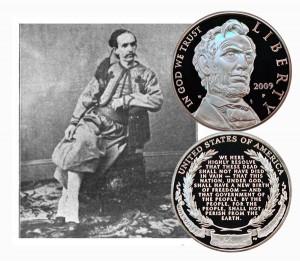

The Lincoln Commemorative Silver Dollar Coin shows against an 1866 image of John H. Surratt in his Papal Zouave uniform at Rome, Italy.