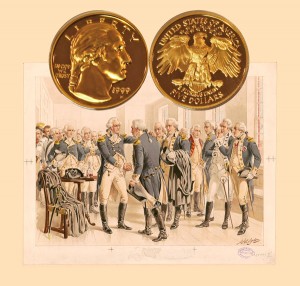

Today, the George Washington Commemorative Gold Five-Dollar Coin remembers the contentious events prior to the official disbanding of the Continental Army 233 years ago.

From the History of the United States, Or, Republic of America, by Emma Willard, published in 1844:

=====

The situation of the rising Republic of America, was, during these long negotiations, extremely critical. Had the government possessed the means of paying their officers and soldiers, there would have been nothing to apprehend from disbanding so patriotic an army.

But the officers, aware of the poverty of the treasury, doubted whether it would be in the power of congress to fulfill the stipulation made in October, 1780, granting to them half-pay for life.

While the independence of their country was uncertain, they had pressed forward to the attainment of that object; and regardless of themselves, had sacrificed their fortunes, and their health.

Now, that great object was attained, they began to brood over their own situation; and fears arose, that should they disband before their country had done them justice, and lose their consequence as a body, they and their services might be forgotten.

Nor were there wanting officers, whose personal ambition carried them beyond the mark of right and justice; and brought up the reflection, that if the army could remain entire under its head, it might now subdue the country which it had defended: and although, if a monarchical government were established, the commander-in-chief must be the sovereign; yet the officers coming in for the next share of power and consequence, would become the aristocracy.

To tempt Washington to countenance these views, one of the older colonels of the army, was fixed upon, who wrote him a letter in a smooth and artful strain.

He commented on the weakness of republics, and the benefits of mixed governments. He insinuated that the same abilities which had guided the country so gloriously through the storm, must now be the most suitable to conduct it through the gentler paths of peace.

There was a prejudice existing which confounded monarchy with tyranny, and it might be necessary to choose, with a monarchical government, some title, apparently more moderate, but the writer believed, “that strong arguments might be produced for admitting the title of KING,” which, he conceived, “would be attended with some material advantages.”

Washington was astonished, displeased, and grieved.

He replied, that no occurrence during the war, had given him more painful sensations, than to learn that such ideas existed in the army—ideas which he “must view with abhorrence, and reprehend with severity.”

“I am at a loss,” said he, “to conceive what part of my conduct could have given encouragement to an address, which to me, seems big with the greatest mischiefs which could befall my country. If I am not deceived in the knowledge of myself, you could not have found a person, to whom your schemes are more disagreeable.

“At the same time, in justice to my own feelings, I must add, that no man possesses a more sincere wish to see ample justice done to the army, than I do; and, as far as my powers and influence, in a constitutional way, extend, they shall be employed to the utmost of my abilities to effect it, should there be any occasion.

“Let me conjure you, then, if you have any regard for your country, concern for yourself or posterity, or respect for me, to banish these thoughts from your mind, and never communicate, as from yourself or anyone else, a sentiment of the like nature.”

Thus nipped in the bud, nothing more was heard of the project of making Washington a king.

But the causes of the army’s discontent remained, although congress had taken some steps towards their removal.

Washington repeatedly urged the subject upon their attention; yet the designing among the officers insinuated, that he had not advocated their cause with sufficient zeal.

The answer to a memorial, which they had presented to congress, had not fully met their wishes.

It was on this occasion that an anonymous paper was circulated, now known to have been written by Major John Armstrong, then an aid-de-camp to General Gates.

It was composed with great ability. Never was a writing more calculated to become a firebrand of discord.

There was truth in its representations of the toils, and yet unrequited dangers and sufferings of the officers: but the country had not deserved the insinuation, of being so far from doing justice to her defenders, that “she trampled on their rights, disdained their cries, and insulted their distresses.”

Yet such was the language of the address.

It advised the officers “to change the milk-and-water style” of their memorial to congress, and no longer appeal to their justice, but keep arms in their hands, and appeal to their fears.

This paper proposed a meeting of the officers on the ensuing day.

Washington, aware of the feelings of the army, had not availed himself of the suspension of hostilities, to seek the pleasures of home, but had remained in the camp.

He now saw that the dreaded crisis had arrived.

Intent on guiding deliberations which he could not suppress, he called his officers to a meeting somewhat later than the one appointed in the anonymous appeal, to which, in his orders, he alluded with disapprobation.

In the interim, he prepared a written address. The officers met.

The Father of his Country rose, to read the manuscript which he held in his hand.

Not being able to distinguish its characters, he took off his spectacles to wipe them with his handkerchief.

“My eyes,” said he, “have grown dim in the service of my country, but I never doubted her justice.”

This was a preface, worthy of the paper which he read.

He alluded in the most touching manner, to the sufferings and services of the army, in which he too had borne his share.

He treated with becoming severity, the proposition, made in the anonymous paper, to seek by unlawful means, the redress of their grievances.

He assured them that congress, though slow in their deliberations, were favorable to the interests of the army; and he conjured them not to tarnish the renown of their brilliant deeds, by an irreparable act of rashness and folly; and finally, he pledged them his utmost exertions to assist in procuring from congress the just reward of their meritorious services.

The officers listened to the voice which they had so long been accustomed to respect and obey; and the storm of passion was hushed.

His pledge of using his influence with congress, in behalf of the army, was performed in a manner which showed how deeply he had their cause at heart.

“If,” said he, in a letter to that body, “the whole army have not merited whatever a grateful people can bestow, then have I been beguiled by prejudice, and built opinion on the basis of error. If this country should not, in the event, perform everything which has been requested in the late memorial to congress, then will my belief become vain, and the hope that has been excited, void of foundation.

“And if, (as has been suggested, for the purpose of inflaming their passions,) the officers of the army are to be the only sufferers by this revolution; if retiring from the field, they are to grow old in poverty, wretchedness, and contempt; if they are to wade through the vile mire of dependency, and owe the miserable remnant of that life to charity, which has hitherto been spent in honor; then shall I have learned what ingratitude is; then shall I have realized a tale which will embitter every moment of my future life.”

Congress used their utmost exertions to meet the exigency.

They commuted the half-pay which had been pledged to the officers for a sum equal to five years’ full pay.

The news that the preliminaries of peace were signed, was first received in a letter from La Fayette.

Sir Guy Carleton soon communicated it officially; and on the 19th of April, just eight years from the battle of Lexington—the beginning of the war, the joyful certainty of its close was proclaimed from head-quarters to the American army.

The officers now satisfied, the army was disbanded without tumult, November 3, 1783.

They mingled with their fellow-citizens, ever through future years to be honored for belonging to that patriotic band.

It is now nearly sixty years since its existence, and still there remains here and there a silver-headed veteran of whom it is said, “he was a revolutionary soldier.”

It is the password to honor.

At all patriotic meetings, the first place is assigned him; and a grateful country has liberally provided for his wants.

=====

The George Washington Commemorative Gold Five-Dollar Coin shows with an artist’s image, circa 1893, of the Farewell to Officers meeting.