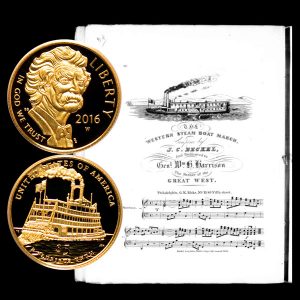

Today, the Mark Twain Commemorative Gold Five-Dollar Coin remembers the first steam boat to arrive in New Orleans on January 10, 1812.

From the Report on the Ship-Building Industry of the United States by Henry Hall, Special Agent, found in The Newspaper and Periodical Press of the Department of the Interior, U. S. Census Office, published in 1884:

=====

Steam boating was introduced to the West by the same men who were the pioneers on the Hudson.

Fulton and Livingston, having secured what they hoped would be a monopoly of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, in 1811 built at Pittsburgh the little stern-wheel boat Orleans, of about 200 tons burden, rigged with masts and sails, the latter to be spread when the rivers were broad and the wind fair. Wood was used for fuel.

The boat was regularly and strongly framed, but had no guards or upper works, and, like all the early boats, only one chimney. January 10, 1812, she arrived at New Orleans for the first time, her speed being about 3 miles per hour.

This pioneer of the rivers ran for two years between New Orleans and Natchez as a packet, and was sunk by a snag near Baton Rouge in 1814.

When the Orleans made this first trip down the Ohio the river was navigated only by small sailing craft and flat-boats, the latter pushed along with poles or rowed with long sweeps, like oars; but the superiority and success of steam was so instantly demonstrated that new steamboats followed as fast as the capital could be secured to build them.

The Comet, a stern-wheeler with vibrating engines, was built at Pittsburgh in 1813, and also ran down to New Orleans, her machinery being sold there for a cotton factory.

The Vesuvius followed, built at Pittsburgh in 1813 by R. W. Fulton, and sent, like the others, to the great river below.

A small steamer of 50 tons was built at Brownsville, on the Monongahela, in 1814, and the same year the Etna, of 300 tons, was launched at Pittsburgh for the trade between Natchez and Louisville.

Wheeling next caught the fever; someone there built the Washington, the first boat with two decks. The machinery, which in previous boats had been placed in the hold, was set up on the deck of the hull—a position it has since retained in all western river boats.

The low power of the engines had made it practicable to employ her predecessors only on the lower Ohio and the Mississippi when the current was less than 3 miles per hour, and they could never ascend the swifter parts of the river after having once gone down.

The Washington was, on the other hand, a powerful boat for her size. After she had gone over the falls of the Ohio at Louisville, she made two trips to New Orleans and back to Shippingport, (a) performing one round trip in 45 days.

Her success was the signal for the construction of a great many small steamboats at different points on the Ohio river, on which stream all the early building took place, and which to-day still produces five-sixths of all the new tonnage of the West.

By 1818 there were half a dozen yards around the falls of the Ohio river near Louisville. Engines were often put in at New Orleans.

In 1818, at Cincinnati, was built the General Pike, famous in her day, intended for passenger traffic exclusively. This boat had a 100-foot keel and 25 feet beam, and a handsome cabin was erected on her deck between the engines.

The central hall measured 40 by 18 feet, and at one end there were 6 and at the other 8 state-rooms for travelers. She ran as a packet between Louisville, Cincinnati, and Maysville.

These early boats were all strong and durable, as they were built from the native oak of the Ohio and were framed and planked on the same plan as boats for the deep sea.

The East at one time aspired to build vessels for the West, and in 1818 the Maid of Orleans, of 100 tons, was sent from the Philadelphia yards. She was a two-masted schooner, with steam-power, for use on the river. She ascended as far as Saint Louis in 1818, and was the first craft that reached that city from an Atlantic port.

There were few ventures of that sort, however. The early steamboats were all small and of low speed; traffic was light in those days, and little was expected of the boats except to carry comfortably and safely the mails, a little general merchandise, and the few travelers who were compelled by political or mercantile errands to pass from point to point in the sparsely settled regions of the West, and if they could breast the current of the rivers and make any sort of speed at all they fulfilled the needs of the times.

After 1820 the country grew rapidly in population. Manufacturing developed along the Ohio, and special attention was paid to the needs of the South.

New Orleans was building up a thriving foreign trade, and the basis was established for a large exchange of products between the lower and the upper portions of the river.

Travel and trade increased; rival steamboats came into existence, which strove to excel each other in speed, size, comfort, carrying power, and general adaptability to the special requirements of the river trade; boat-yards were established all along the banks of the Ohio, at Saint Louis, and at New Orleans; and for more than 50 years steamboat building flourished in the West, reaching large proportions.

The yards were scattered principally along the Monongahela and Ohio. Active work was done at Brownsville, Pittsburgh, Allegheny City, Sewickley, and Freedom, Pennsylvania; Steubenville, Marietta, Ironton, and Cincinnati, Ohio; Wheeling, Virginia; Newport, Louisville, and Portland, Kentucky; Madison, New Albany, and Jeffersonville, Indiana; Cairo and Mound City, Illinois; Saint Louis, Missouri; Dubuque, Iowa; Stillwater, Minnesota, and New Orleans.

Besides yards at these places, a large number grew into existence at intermediate points for the repairing of vessels or for the building of barges and flat-boats, or for both repairing and building. The early boats were all of low speed, as has been before noted, and up to 1818 no faster trip had been made from New Orleans to Louisville than 19 days.

The Shelby had made the trip in that time with 51 passengers and a cargo of groceries, dry goods, etc., having stopped at ten places en route. Her running time was 15 days and 5 hours, but the usual time up the river was from 25 to 30 days.

The fast steamer Cincinnati made round trips from Cincinnati to New Orleans in about 40 days, but once consumed nearly 100 days on the upward trip alone, having broken down en route, finding no place where repairs could be made until she reached Louisville.

Efforts were finally made to improve the time of passenger boats, especially after 1830, and with such success that in 1838 the Diana made the run from New Orleans to Louisville in less than 6 days, winning a premium of $500 from the Post-Office Department for so doing.

The passenger boats were side-wheelers, with pretty sharp bows and flat floors amidships, drawing from 4 to 6 feet of water, and were from 400 to 600 tons register. In the smaller boats the cabin was on the main deck aft between the engines.

In 1838 upper cabins were rare, but they came into popularity later; cabins are now never placed on the main deck, except in a few ferry-boats.

When the era of fast boats began, in 1830, the speed of every new-comer from the ship-yard was tested, and the course selected for this purpose was the lower Mississippi, which was deep and comparatively free from bars.

Racing over this course from New Orleans to the cities north became the fashion after 1830, and has remained a feature of western boating to the present day.

Rivalry reached such a point at times that both before and after the late war boats were sent over the course, stripped of every pound of cargo, baggage, and encumbrance, including even a part of the wood work of the vessel, and were driven with the full power of the engines and sent along without making stops, merely to beat the record of all previous trips and establish a reputation for speed.

The passion for fast time and the carrying of steam at high pressure led to immense loss of life and property by explosions until legislation interfered and regulated the pressure of steam and the strength of the boilers.

The speed of later boats has been secured not so much by an increase of steam pressure as by enlarging the cylinders of the engines.

…

=====

The Mark Twain Commemorative Gold Five-Dollar Coin shows with an image of the first page of the Western Steam Boat March, circa 1840.